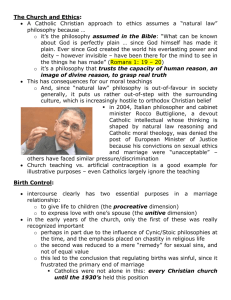

religious liberty and the culture wars

advertisement