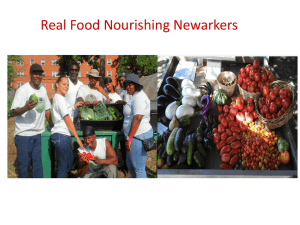

No Work iN NeWark - Institute for Justice

advertisement