SOK History copy

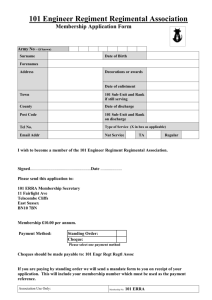

advertisement