the publication in PDF

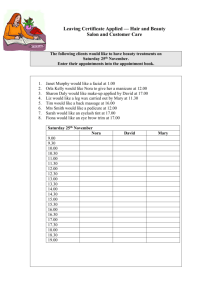

advertisement