Preview - Insight Publications

advertisement

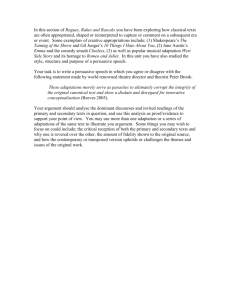

SA M PL E PA G ES English Year 11 Robert Beardwood with Sandra Duncanson Virginia Lee Melanie Napthine Table of contents Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . v Course overview. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . vi Chapter 1: Novels and short stories 2 Key features of narrative texts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4 Special features of short stories. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14 Chapter 2: Film 17 Cinematography. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18 Mise en scène . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20 M PL E Sound. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21 Sample scene analysis. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23 Vocabulary for film . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24 Chapter 3: Drama Chapter 6: Ideas, issues and themes 25 47 Themes and ideas. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48 Issues. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50 Values . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50 Analysing ideas, issues and themes. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52 PA Vocabulary for novels and short stories. . . . . . . . . . . . . 15 ES 1 G Area of study Reading and creating texts Reading and comparing texts Chapter 7: Analytical text responses 53 Analyse the topic. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54 Plan your text response. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56 Write your text response. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60 Edit your work. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 64 Build your skills. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 64 Annotated sample responses. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65 Chapter 8: Creative text responses 71 Planning a creative response. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72 Structure. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26 Developing a creative response. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73 Stage directions and stage sets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28 Guidelines for a written explanation. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75 Dialogue, soliloquies and asides . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29 Text types and sample responses. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75 SA Special features of drama. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26 Vocabulary for drama. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31 Chapter 4: Non-fiction narratives 33 Types of narratives. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34 Point of view and selection of events. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35 Importance of context and setting. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36 Time lines and subjects. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36 Vocabulary for non-fiction narratives. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38 Chapter 5: Poetry 39 How to analyse a poem. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40 Vocabulary for poetry. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45 Chapter 9: Comparing texts: strategies and guidelines 91 Identifying shared ideas, issues and themes. . . . . . . 92 How texts present ideas, issues and themes . . . . . . 98 Exploring different perspectives . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102 Chapter 10: Writing a comparative text response 111 How to structure a comparative essay . . . . . . . . . . . . 112 Guidelines for writing a comparative essay . . . . . . . . 114 Sample topics, analyses and annotated responses. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 122 insight E n g l i s h Y e a r 1 1 iii Table of contents Chapter 11: Understanding argument and persuasive language 2 134 Chapter 15: Persuasive language techniques 178 Argument. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 137 Examples and activities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 180 Language . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 138 Chapter 12: Newspaper texts 142 Print versus digital newspapers. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 143 Choosing the news. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 144 Headlines. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 145 Chapter 16: Writing an analysis Opinion pieces and blog entries . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 148 Letters to the editor and online comments . . . . . . . 150 Cartoons. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 151 Photographs. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 152 Chapter 13: Other media texts 155 188 Preparing your analysis. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 189 Planning your analysis. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 190 Writing your analysis. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 190 Sample issue and annotated analysis. . . . . . . . . . . . . 194 M PL E Editorials. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 146 G Main contention. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 135 Summary table of persuasive language techniques. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 179 PA Audience and purpose. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 135 ES Area of study Analysing and presenting argument Chapter 17: Presenting a point of view 198 What is an issue?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 199 How to develop a reasoned point of view. . . . . . . . . 200 Sample issue and point of view. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 202 Tips for oral presentations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 207 How to write a statement of intention . . . . . . . . . . . . 208 Television news and current affairs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 156 SA Radio news and talkback programs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 157 Chapter 18: The exam 210 Internet texts. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 158 Format of the exam. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .211 Speeches. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 160 Timing in the exam. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 211 Chapter 14: A rgument: persuasive strategies and techniques 161 Understanding argument. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 162 Area of Study 1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 211 Area of Study 2. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 214 Proofreading and revising your answers. . . . . . . . . . . 215 Structuring strategies. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 164 Summary table of argument techniques. . . . . . . . . . 166 Acknowledgements. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 216 Examples and activities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 167 Index. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 217 A holistic approach. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 174 iv insight E n g l i s h Y e a r 1 1 Introduction Insight’s English Year 11 is a practical, comprehensive textbook for VCE English Units 1 and 2. It is closely based on English in Year 11, with new chapters specifically written for the revised VCE English Study Design, which is accredited for Year 11 students from 2016. The main new elements of the course are: a creative text response in Area of Study 1 (Unit 1) ●● a comparative text response in Area of Study 1 (Unit 2) ●● the analysis of argument as well as persuasive language in Area of Study 2 (Units 1 and 2). ES ●● PA G These elements are specifically addressed in chapters on creative responses (Chapter 8), comparative responses (Chapters 9 and 10) and the analysis of argument (Chapter 14). However, all the chapters contribute in important ways to developing your overall understanding of the subject, and your ability to complete the required tasks. M PL E Throughout this book there are many explanations, word banks, model paragraphs and complete sample responses to show what you need to know as well as how you need to write. In addition, there are numerous activities that are graded from those that require short, simple answers up to extended paragraphs. Completing the activities will build your detailed knowledge of texts, as well as your confidence in writing. Knowledge and skills are very closely linked: put your knowledge into practice as soon as possible, and as often as possible. SA Each assessment task is covered in detail, with at least one complete sample response. The annotations point out the elements of each response that satisfy the task requirements, as well as the key things your teachers will be looking for in your writing. English Year 11 gives you all the tools you need for a successful Year 11, and provides ideal preparation for Year 12. insight E n g l i s h Y e a r 1 1 v Course overview UNIT 1 UNIT 2 Reading and creating texts Reading and comparing texts You will study: You will study: ES You will produce: • analytical responses to texts • analytical responses to a pair of texts, comparing their presentation of ideas, issues and themes. You will study: You will study: • analytical responses to a text M PL E English You will produce: • analyses of how argument and persuasive language are used to position an audience You will produce: EAL comparing their presentation of ideas, issues and themes. You will produce: • texts to position an audience. Oral requirement • analytical responses to a pair of texts, Analysing and presenting argument • analyses of how argument and persuasive language are used to position an audience • texts to position an audience. vi You will produce: Analysing and presenting argument SA Area of study 2 • creative responses to a text. • two texts selected by your school. PA • one text selected by your school. You will produce: • two texts selected by your school. G English You will produce: • creative responses to texts. EAL area of study 1 • two texts selected by your school. One (and only one) assessment task for Unit 1 must be in oral or multimodal form. insight E n g l i s h Y e a r 1 1 • analyses of how argument and persuasive language are used to attempt to influence an audience • texts to present a point of view. You will produce: • analyses of how argument and persuasive language are used to attempt to influence an audience • texts to present a point of view. All assessment tasks for Unit 2 must be in written form. Area of study 1 ES s t x e t g n i t a e r c d n a g n s Readi t x e t g n i r a p m o c d n a Reading Getting started PA G Studying texts is a major part of your VCE English course. Area of Study 1 focuses on reading and understanding texts such as novels, stories, plays, films and poetry, then responding to them, usually in an extended piece of writing. In Year 11 English you will study four texts in detail, two in each semester. Year 11 EAL students study three texts during the year. M PL E Your set texts will explore a range of situations and events, and offer insights into human experience. Such texts help us to reflect on how individuals respond to challenge and adversity, what they value, what gives them hope and why they behave the way they do. In this section 1 Novels and short stories 2 Film SA 3 Drama 4 Non-fiction narratives 5 Poetry 6 Ideas, issues and themes 7 Analytical text responses 8 Creative text responses 9 Comparing texts: strategies and guidelines 10 Writing a comparative text response In Unit 1 the focus is on responding to each text individually, either analytically or creatively. In Unit 2 your text responses will analyse a pair of texts, comparing and contrasting their exploration of shared ideas, issues and themes. To use this book, first go to the chapter relevant to your text type: Chapter 1 for novels and short stories, Chapter 2 for film, Chapter 3 for plays, Chapter 4 for non-fiction narratives, Chapter 5 for poetry. Then look at the text’s wider meaning – the ideas, issues and themes it explores – using the tools and strategies in Chapter 6. Finally, go to the chapter or chapters relevant to the text response you need to create. For an analytical response, see Chapter 7. For a creative response, see Chapter 8. When you are writing a comparative essay on two texts, see Chapters 9 and 10. Remember, every text response must be based on a close knowledge and thorough understanding of your set texts. insight E n g l i s h Y e a r 1 1 | Area of Study 1 1 * * * Identifying shared ideas, issues and themes How texts present ideas, issues and themes Exploring different perspectives PA G In this ch apter ES chapter 9 Comparing texts: strategies and guidelines SA M PL E A comparative essay demonstrates your close knowledge and understanding of two texts. It enables you to consider each text in detail, and also to compare and contrast the two, using each text as a means to see what is unique and insightful about the other. The process of reading and responding to two texts together will enhance your understanding of each. This chapter shows you how to build ideas and gather evidence through your close study of the texts. You will be looking for similarities or parallels, as well as differences in their perspectives on shared ideas, issues and themes. The ideas themselves might vary slightly between the texts, especially if they were written in very different times or places. Just as crucially, creators of texts can present similar ideas and themes in ways that contrast significantly, depending on their choice of form and their use of features such as narrative viewpoint, setting, plot, language and imagery. Your response will be a formal written essay on a set topic or question – see Chapter 10 for detailed guidelines as well as sample topics, analyses and responses. insight E n g l i s h Y e a r 1 1 | Area of Study 1 91 Chapter 9 Comparing texts: strategies and guidelines Identifying shared ideas, issues and themes When comparing texts, your focus will be on the ideas, issues or themes they share. Once you have identified these shared concerns, you can analyse the different perspectives each text brings to them, such as: considering similar ideas in different historical, social or cultural contexts ●● presenting different points of view on an idea or issue ●● asking different ‘big questions’ about an idea ●● exploring different consequences of an idea or an issue in society ●● using features of the text form (e.g. novel, play, film, non-fiction narrative) to highlight problems or explore questions – which is especially relevant when the two texts have different forms. G PA Text pairs used for examples ES ●● Throughout this and the next chapter, the following texts are used to provide examples of various approaches to comparing two texts. Even if you are not familiar with these texts, the analyses and sample responses will still provide useful models for your own writing. You will be able to apply the general guidelines and activities to your own texts. M PL E The dates in brackets indicate when the print text was first published or, for a film, the year of first release. Texts Key ideas, issues & themes • justice Reginald Rose, Twelve Angry Men (play, 1955) • prejudice Tracy Chevalier, Girl with a Pearl Earring (novel, 1999) • women asserting power in the face of limited opportunities Martin Scorsese (director), The Age of Innocence (film, 1993) • subverting strict social conventions SA Larry Watson, Montana 1948 (novel, 1993) • integrity • negotiating/resolving conflict and freedoms • love • appearances versus underlying reality • things that remain unsaid Geraldine Brooks, Year of Wonders (novel, 2001) • fear in response to plague Stephen Soderbergh (director), Contagion (film, 2011) • family and community bonds being tested • remaining true to one’s values under pressure • how people respond when facing death • truths revealed/exposed in times of crisis 92 insight E n g l i s h Y e a r 1 1 Comparing texts: strategies and guidelines Chapter 9 Texts Key ideas, issues & themes Kazuo Ishiguro, Never Let Me Go (novel, 2005) • oppression/inequality Ridley Scott (director), Blade Runner (film, 1982) • the importance of human dignity and individuality • what it means to be human • technology leading to ethical problems • love • the importance of memory to identity Michael Gow, Away (play, 1986) • the search for identity Ivan Sen, Beneath Clouds (film, 2001) • journeys/quests • discovery • experiences of loss • city versus country/coast G • family (tensions and fragmentation) ES • confronting mortality • integrity Robert Bolt, A Man for All Seasons (play, 1960) • power being enforced through violent means PA Elia Kazan (director), On the Waterfront (film, 1954) • standing up to external pressures • corruption • religious values/leadership • responses of people caught up in violent conflict Chloe Hooper, The Tall Man (non-fiction, 2008) • the struggle for human rights M PL E Brian Friel, The Freedom of the City (play, 1973) • the fallibility or corruption of the legal/justice system • colonial powers using violent means to persecute people in their homeland Themes: similarities and differences between texts SA Consider the mind maps for Twelve Angry Men on pages 48 and 49. The first map shows several major themes in the play – and if you are studying this text you could easily add more. Identify as many shared ideas, issues and themes as you can in the texts you are comparing; don’t limit your thinking to one or two main ideas. You might even find that additional themes come into the foreground in the process of your comparison. For example, a comparison of Twelve Angry Men with Montana 1948 might focus on the shared themes of justice, prejudice and integrity. However, if you compare their approaches to resolving conflict, you might decide that this is a much more central theme in each text than you had thought. insight E n g l i s h Y e a r 1 1 | Area of Study 1 93 Chapter 9 Comparing texts: strategies and guidelines Venn diagrams showing themes in two texts A Venn diagram is a concise visual way to show similarities and differences between themes and ideas in two texts. Below is a simple Venn diagram showing some of the main themes in Twelve Angry Men and Montana 1948. human fallibility compassion family growing up prejudice integrity power gender roles PA doubt/certainty justice G truth montana 1948 ES Twelve Angry Men M PL E When comparing texts your focus is, of course, on the themes in the intersection of the two circles. However, you should still think about the themes that fall only in one circle, as they might well influence the way in which a text explores one of the shared themes. Draw a Venn diagram to show themes Create a Venn diagram showing a range of themes in your two texts. Think carefully about where you place each one; you might find the two texts have more in common than you first imagined. Keep the themes and ideas simple at this stage – use single words or short phrases, as in the example above. You can add to this as you continue your study of the texts. The second map in Chapter 6 for Twelve Angry Men (page 49) shows different aspects or forms of the main theme of justice. Even when two texts have a main theme or idea in common, each author will take up different aspects of the theme, and express different points of view on it, in relation to the story they are telling and the characters they have created. Identifying different aspects of a main theme will therefore give you some key points for comparing and contrasting two texts. 94 insight E n g l i s h Y e a r 1 1 Activity SA In Twelve Angry Men, the difficulty of establishing the truth about events leading up to the murder of the accused’s father is central to the exploration of justice. In Montana 1948, in contrast, there is never any doubt about Frank’s guilt. Yet the novel also explores doubts and uncertainties – such as those experienced by Frank’s brother Wes, the town sheriff. * * * How to structure a comparative essay Guidelines for writing a comparative essay Sample topics, analyses and annotated responses Comparative text responses share many features with analytical text responses on a single text. Each response: ●● takes a position on a given essay topic presents a line of argument about, and a consistent interpretation of, the texts SA ●● is a coherent essay, with an introduction, body paragraphs and a conclusion M PL E ●● PA G In this ch apter ES chapter 10 Writing a comparative text response ●● includes detailed textual evidence, including brief quotations, to support the argument and reasoning. On the other hand, comparing two texts requires a balancing act – a balance between the two texts, and between writing about an individual text and writing about two texts together. Some of your analysis will focus on a single text, showing your in-depth understanding of characters, plot, narrative and language. Other paragraphs will compare and contrast both texts. This will be particularly important in your final paragraph or two. The following sections show you ways to structure your comparative essays, appropriate language for comparing and contrasting texts, and strategies for analysing the main types of topics. The three sample responses at the end of this chapter include notes on planning the essays as well as detailed annotations. Even if you are not studying these particular texts, use the notes and annotations as guides for your own writing. insight E n g l i s h Y e a r 1 1 | Area of Study 1 111 Chapter 10 Writing a comparative text response How to structure a comparative essay The diagrams and explanations below show you three main ways to structure a comparative response. Each structure ensures that your essay is coherent – that is, it develops an argument in a consistent and logical manner. Note that the boxes in the flow charts indicate the overall structure, rather than the number of paragraphs required. The in-depth discussion of each text might cover two or even three paragraphs, depending on paragraph length and the overall length of your essay. ES A block essay G This is the most straightforward structure. It ensures that you deal with both texts in detail, and that your response focuses on the ideas, issues or themes identified in the introduction. It does restrict your comparison of the two texts to the final paragraph or two, so remember to make this part of the response just as detailed and thorough as the rest. PA Introduction: state your position or argument in response to the topic, with brief reasons, referring to both texts. Discuss ideas, issues and themes in text 1. M PL E Discuss the same or similar ideas in text 2. Discuss both texts, indicating similarities and differences, finishing with one or two concluding statements. SA The introduction ‘sets up’ your discussion by stating your point of view, or main contention, in response to the topic. In the body paragraphs, link back to your main contention; the final sentence of a paragraph is a good place to make this link. You might also wish to add a brief conclusion to sum up and restate your position on the topic. Block essay with transition paragraph This structure is slightly more complex than the block approach above. If you can become comfortable with it, your responses should have: ●● more fluency, as there is a smooth transition from discussion of one text to the next ●● more detailed discussion of similarities and differences between the texts. In this structure, you can devote more space to a side-by-side comparison of the texts, examining both similarities and differences. As in your detailed discussion of each individual text, your comparison of the two texts must be supported by textual evidence. You might emphasise similarities or focus on differences and contrasts, depending on the topic and your interpretation of the texts. 112 insight E n g l i s h Year 11 Writing a comparative text response Chapter 10 Introduction: state your position or argument in response to the topic, with brief reasons, referring to both texts. Discuss ideas, issues and themes in text 1. In a transitional paragraph, discuss similarities and differences between the texts. ES Discuss similar ideas in text 2. G Discuss both texts in a concluding paragraph. A more complex structure based on ideas PA This structure organises the paragraphs according to the ideas discussed, rather than discussing the texts one after the other. Comparison of the two texts occurs throughout the response, rather than just in particular paragraphs. M PL E Introduction: state your position or argument in response to the topic, with brief reasons. Discuss one key similarity or difference between the texts. Discuss another key similarity or difference. SA Discuss another key similarity or difference. Discuss both texts in a concluding paragraph. To give this response more shape and coherence, you could begin with similarities and move on to consider differences, or vice versa. Planning is very important when using this structure, as each key similarity or difference needs to be clearly identified in a topic sentence. As in the previous two structures, it is very important that you write in depth and detail on each text. You still need to convey a thorough understanding of each text, as well as examine the similarities and differences between them. If you adopt this integrated approach, avoid shifting back and forth between your texts too many times in each paragraph. Write in detail on one text, then discuss the same point in relation to the other. insight E n g l i s h Y e a r 1 1 | Area of Study 1 113 2 Area of study ES g n i t n e s e r p d n a g n i s y l a An argument Getting started 11 Understanding argument and persuasive language Persuasive texts are part of our daily lives. We hear them on the radio and on television in news, current affairs and radio talkback programs and, of course, in advertisements. We read and view them in the opinion columns of newspapers, media websites and blogs. 13 Other media texts To be effective, persuasive texts combine an argument with persuasive language. The argument is the overall point of view or message being conveyed, as well as the supporting reasons and evidence. Arguments can be presented in a very logical way, emphasising facts and figures; or they can be presented in a very emotional way, seeking to arouse and influence people’s feelings. Often they combine the two approaches, appealing to both ‘head’ and ‘heart’ to create the strongest impact on a reader or listener. M PL E 14 Argument: persuasive strategies and techniques PA 12 Newspaper texts G In this section 15 Persuasive language techniques 16 Writing an analysis SA 17 Presenting a point of view To support the argument, a range of persuasive language techniques will be used to position the reader or listener and influence their viewpoint on an issue. The language will also be carefully chosen to achieve the writer’s purpose with their intended audience. That is, argument and language work together to present a point of view in the most convincing and effective way possible. In your study of media texts you will analyse how argument and language are used in relation to an issue that is currently being debated – perhaps locally, or across the nation, or even internationally. You will also present your own point of view on an issue, combining argument and persuasive language to persuade others to agree with you. insight E n g l i s h Y e a r 1 1 | Area of Study 2 133 ES Understanding argument Structuring strategies Summary table of argument techniques Examples and activities A holistic approach G * * * * * M PL E PA In this ch apter SA chapter 14 Argument: persuasive strategies and techniques An argument is a clear contention justified by supporting reasons. Strong arguments use logic and reasoning to demonstrate the validity of the writer's or speaker's viewpoint. Constructing a strong argument involves making careful choices about the order in which to present supporting reasons and appropriate techniques to persuade the audience and rebut opposing arguments. Strong arguments are also presented in appropriately persuasive language. (See Chapter 15 for more information about persuasive language techniques.) insight E n g l i s h Y e a r 1 1 | Area of Study 2 161 Chapter 14 Argument: persuasive strategies and techniques Summary table of argument techniques Use this table as a quick reference to build your understanding of argument techniques and strategies and how they are used to persuade the reader, viewer or listener. Analogy A comparison between two things that helps the reader to draw conclusions about their similarities. Anecdote A story about someone or something that the writer has experienced or heard about. Appeal to family values Gains attention; adds emphasis; often in headlines. ➜ Draws attention to key words. ➜ Not persuasive on its own but can be when used with other techniques. ➜ Explains a complex point in more familiar terms. ➜ Can help to make the contention look simple and obvious by linking it to something that readers know well. ➜ Personal experience lends weight/credibility to the writer’s viewpoint. ➜ Gives a human angle, making the issue seem more relevant or ‘real’. ➜ Invokes the reader’s desire for emotional security and a protective, nurturing environment for children. ➜ Can be implicit when antisocial behaviour is blamed on broken or dysfunctional families. M PL E Suggests that families are good, especially traditional nuclear families. ➜ Appeal to fear and insecurity Arouses fear and anxiety by suggesting that harmful or unpleasant effects will follow. Appeal to the hip-pocket nerve Suggests that people should pay the least amount possible, either individually or as a society. Appeal to loyalty and patriotism SA Suggests that readers should be loyal to their group and love their country. Appeal to tradition and custom Suggests that traditional customs are valuable and should be preserved. Begging the question Occurs when the premise of an argument is the same as the conclusion. Deductive reasoning Examining general rules and facts about a group to form a specific conclusion about one part of the group. 166 insight E n g l i s h Year 11 Anyone who objects to hunting animals for sport but isn’t a vegan is a self-righteous hypocrite whose opinion lacks any moral weight or validity. ES Attacking or insulting a person rather than their opinion or the facts. Example Yes, poaching is more damaging than trophy hunting. Murder is worse than grievous bodily harm, technically, but I’m comfortable strongly objecting to both. G Ad hominem attack How the technique persuades Incredibly, the idiot motorist who didn't see me cycling along Beach Road and sent me to hospital for five months did not even get a fine. PA Argument technique and definition ➜ Makes the reader want to lessen the threat to themselves or society by taking the writer’s advice. ➜ Plays on people’s fears. ➜ Positive impact: makes the reader pleased about getting value for money. ➜ Negative impact: makes the reader annoyed about paying too much or about the misuse of money. ➜ Invokes feelings of pride, a shared identity and common purpose. ➜ Often uses inclusive language to emphasise these feelings. ➜ Traditional customs have positive associations, e.g. with ideas of family and social unity, inclusiveness, sharing. ➜ Often compared positively with ‘modern’ lifestyles to make readers feel that social cohesion is being lost. ➜ Reassures the reader through a familiar expression. ➜ Lulls the reader into an uncritical mindset. ➜ Often has a comic effect. This can produce a lighthearted, amusing tone, or a sarcastic, critical tone. ➜ Encourages the reader to respond on an emotional level. ➜ The reader’s emotional response positions them to share the writer’s viewpoint. The new childcare package provides nothing for families who believe that for babies and young children, bonding with parents in the home is superior to care provided by strangers, however well trained they may be. Hoon drivers are recklessly and callously putting innocent lives in serious danger. Over the past decade, Australian gas and electricity prices have ballooned, leaving an alarming number of Australians struggling to afford these basic necessities. We mustn’t lose sight of the values this wonderful country of ours was built on – equality and a fair go for all. All businesses should be closed on Anzac day to observe and maintain the traditional day of respect. Eating well is the best way to improve our health outcomes both individually and collectively, because eating well will result in fewer illnesses and improved wellbeing. Students often get anxious about exams so the three students absent from class today are probably trying to avoid the test.