a basic guide for paralegals: ethics, confidentiality and privilege

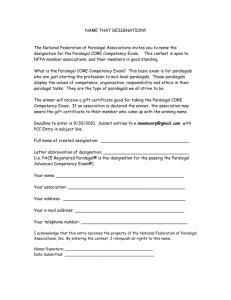

advertisement