To view the pages in pdf form, click here.

advertisement

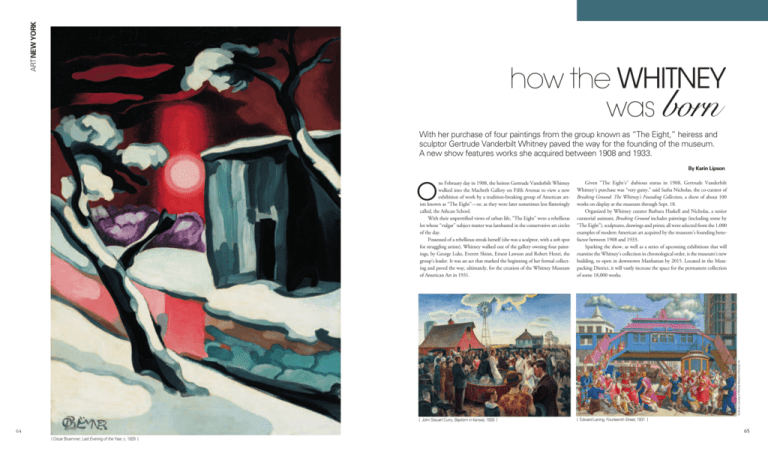

ARTNEW YORK how the Whitney was born With her purchase of four paintings from the group known as “The Eight,” heiress and sculptor Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney paved the way for the founding of the museum. A new show features works she acquired between 1908 and 1933. By Karin Lipson O Given “The Eight’s” dubious status in 1908, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s purchase was “very gutsy,” said Sasha Nicholas, the co-curator of Breaking Ground: The Whitney’s Founding Collection, a show of about 100 works on display at the museum through Sept. 18. Organized by Whitney curator Barbara Haskell and Nicholas, a senior curatorial assistant, Breaking Ground includes paintings (including some by “The Eight”), sculptures, drawings and prints; all were selected from the 1,000 examples of modern American art acquired by the museum’s founding benefactor between 1908 and 1933. Sparking the show, as well as a series of upcoming exhibitions that will examine the Whitney’s collection in chronological order, is the museum’s new building, to open in downtown Manhattan by 2015. Located in the Meatpacking District, it will vastly increase the space for the permanent collection of some 18,000 works. [ John Steuart Curry; Baptism in Kansas, 1928 ] [ Edward Laning; Fourteenth Street, 1931 ] All photos: Courtesy of Whitney Museum of American Art ne February day in 1908, the heiress Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney walked into the Macbeth Gallery on Fifth Avenue to view a new exhibition of work by a tradition-breaking group of American artists known as “The Eight”—or, as they were later sometimes less flatteringly called, the Ashcan School. With their unprettified views of urban life, “The Eight” were a rebellious lot whose “vulgar” subject matter was lambasted in the conservative art circles of the day. Possessed of a rebellious streak herself (she was a sculptor, with a soft spot for struggling artists), Whitney walked out of the gallery owning four paintings, by George Luks, Everett Shinn, Ernest Lawson and Robert Henri, the group’s leader. It was an act that marked the beginning of her formal collecting and paved the way, ultimately, for the creation of the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1931. 64 65 [ Oscar Bluemner; Last Evening of the Year, c. 1929 ] ARTNEW YORK how the Whitney was born [H oward G. Cushing; Mrs. Harry Payne Whitney, (Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney) 1902 ] [ Preston Dickinson; Industry, c. 1923 ] [ Max Weber; Chinese Restaurant, 1915 ] The museum has long outgrown its current Marcel Breuer-designed building on Madison Avenue. “We don’t have a lot of space here for our collection, and we have a lot of fabulous things,” Nicholas said. Given the space limitations, some of those things —pieces that are “perhaps less canonical,” she said—“tend to remain in storage.” Breaking Ground dusts off some of those stored works but isn’t a literal preview of how things will be arranged in the new building, Nicholas said. Rather, she said, it’s part of an ongoing re-evaluation process intended to ignite “new thinking about the collection.” In one sense, Breaking Ground follows the path of many recessionstrained museums that are taking a second, and then a third, look at their own holdings as sources for new exhibitions, while cutting back on costly loan shows. “Every museum right now has the financial reasons for 66 wanting to look at [its own] collection,” Nicholas agreed. But “for us, it’s equally part of thinking about the fact that we’re going to have a lot more space for our collection in three-and-a-half years.” Visitors to Breaking Ground can expect to find some stars of the collection, along with pieces its co-curator calls “quirkier, or by a well-known artist but not necessarily the most iconic.” Still others are by artists considered important in their time, but “quite obscure in the present day. Some of it is a study of how taste changes.” Among those definitely in the “iconic” column: Edward Hopper’s stark 1930 Early Sunday Morning, with its deserted street of red brick buildings and stores; the Precisionist Charles Demuth’s 1927 My Egypt, a view of (despite its exotic title) grain elevators; George Bellow’s 1924 Dempsey and Firpo, a late example of his raw, action-packed boxing pic- tures. Charles Sheeler, Demuth’s fellow Precisionist, is also in the show. Despite her upper-crust origins, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney had rather democratic collecting tastes. Her collecting was guided by Juliana Force, who became the museum’s first director: Whitney might buy a Regionalist painting like John Steuart Curry’s Baptism in Kansas, but she also bought work by the modernists Stuart Davis, Max Weber and Oscar Bluemner. She also supported artists financially. When Curry “came to New York and hadn’t quite found himself yet, she gave him a stipend, and he was able to travel back to Kansas, and develop as a Regionalist,” Nicholas said. Curry’s 1928 Baptism in Kansas, she said, is “one of the earliest icons” of a style often associated with the Great Depression. Another Regionalist, and one of Nicholas’ favorites in the show, is Clarence Carter. An Ohio painter especially active in the ’30s, “he’s not somebody who’s well known,” Nicholas Whitney Museum of American Art said. But he “often adds a kind 945 Madison Avenue at 75th Street; of surreal or magical realist qual212-570-3600; whitney.org ity to his paintings that makes them quite surprising. “We only have one canvas, Immortal Water, the scene of a decaying house along the Ohio River where he was born,” Nicholas said. “It’s kind of an allegory about change and what’s impermanent.” Which, come to think of it, may be especially apt for a show that is, at least partly, about changing artistic tastes. n Karin Lipson, a former arts writer and editor for Newsday, is a frequent contributor to The New York Times. Her last article in Promenade was on “Treasures from the Forbidden City” at the Met. 67