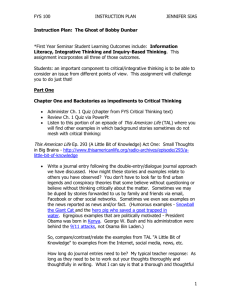

Mitchell_georgetown_0076M_11579

advertisement