The House Discharge Procedure and Majoritarian Politics

advertisement

The House Discharge Procedure and Majoritarian

Politics∗

John W. Patty

Department of Government

Harvard University

September 22, 2006

Abstract

This paper discusses the details of the discharge procedure in the House of Representatives and their implications for theories of legislative politics. While the discharge

procedure is frequently cited as the tool by which committee obstruction within the

House can be overcome, I argue that, under close examination, the procedure actually

is far from purely majoritarian. Specifically, I argue that the details of the discharge procedure imply that the support of either the Speaker of the House or a majority of the

Rules Committee is necessary to ensure floor consideration for a bill. Accordingly, in a

de jure sense, the House’s discharge procedure is irrelevant.

∗

I thank Jim Alt, Barry Burden, Sean Gailmard, Scott Moser, Maggie Penn, Eric Schickler, Ken Shepsle, three

anonymous reviewers, and the Editor for their insightful and very helpful comments.

1

1 Introduction

There is an active debate about the nature of Congressional institutions and their role in determining policy outcomes. Much of the recent theoretical debate has centered on whether

the House of Representatives is “majoritarian.” As defined by Keith Krehbiel, a majoritarian

institution is one in which

“objects of legislative choices in both the procedural and policy domains

must be chosen by a majority of the legislature.” (Krehbiel (1991), p.16)

The approval of the standing rules of the House of Representatives clearly comports with

Krehbiel’s definition: approval requires a majority of legislators voting, a quorum being

present. However, the true nature of day-to-day decision making within the House is not

so unambiguous. There are many reasons for the ambiguity, including the use of procedures such as suspension of the rules, the tying of committee memberships to party caucus

memberships,1 and the special ability of certain committees to report certain matters to the

floor at any time. However, the primary focus of the debate concerning the majoritarian nature of House decision making is the apparent power of standing committees to “bottle up”

legislation. This “gatekeeping” power serves as the basis for several theories of Congress,

including those within the distributive,2 partisan,3 or informational4 traditions. This paper

attempts to refine our theory of the institutional details of the US House of Representatives

by examining what appears to be the most potent neutralizer of gatekeeping: the House’s

discharge rule (House Rule XV, clause 2).

1

House Rule X, clause 5.

This strand of the Congressional literature includes Shepsle (1979) and Shepsle and Weingast (1982),

among many others.

3

Including, but not limited to, Rohde (1991, 1994), Cox and McCubbins (1993, 2005a), Aldrich (1994, 1995),

and Aldrich and Rohde (2000, 2004)

4

The seminal works in this literature include Gilligan and Krehbiel (1987) and Krehbiel (1991).

2

2

The discharge rule has recently attracted significant attention from Congressional scholars.5 This attention has been motivated by the role that discharge plays in distinguishing between several theories of Congress. In addition, the possibility of discharge is theoretically

central to legislative policymaking – and especially so for those who wish to link majority

preference with legislative policy outcomes. As Burden (2005) describes it, the possibility

of discharge “represents the opportunities” for majority preference to be expressed within

the House. Burden’s depiction is highly accurate: the discharge rule is the only procedure

within the standing rules of the House by which a majority can circumvent obstruction by

committee members and the House leadership.

In this paper, following recent work by Schickler and Rich (1997a,b), Cox and McCubbins

(1997), Krehbiel (1999), Schickler (2000), and Crombez et al. (2006), I relate the details of

the discharge process to the theoretical study of Congress. The main point of the paper’s

analysis is that the discharge process, as governed by the standing rules of the House, is not

purely majoritarian. In particular, the paper’s main result is that the rules of the discharge

process imply that securing floor consideration for a measure requires the consent of the

Speaker or a majority of the Rules Committee. In a de jure sense, then, the standing rules

of the House are not majoritarian. Accordingly, even without accounting for the costliness

of the discharge process,6 it is premature to conclude that a measure will be enacted simply

because it is supported by a majority of the members of the House.

The conclusion of the paper is that, in line with the argument of Schickler (2002), a complete theoretical explanation of institutional choice and policymaking within the House requires a combination of partisan, procedural, and policy-seeking approaches (Krehbiel et al.

(1987)). More specifically, at least in de jure terms, understanding what gets voted upon

5

Examples include Krehbiel (1995, 1998, 1999), Binder et al. (1999), Martin and Wolbrecht (2000), Lindstadt

and Martin (2003), Burden (2004, 2005), and Crombez et al. (2006).

6

Examples of this costliness are numerous: retribution by party leaders (Cox and McCubbins (1993, 2005b)),

retribution by the Rules committee (Oleszek (2001), Peabody (1985)), and the potential loss of the informational advantages of the committee(s) being discharged (Gilligan and Krehbiel (1989b)).

3

in the House requires understanding the preferences and behaviors of membership of the

Rules Committee (Dion and Huber (1996, 1997), Krehbiel (1997)). An important implication of this paper’s analysis of the rules of the House is that any claim of formal gatekeeping

powers within the House must center its attention on the Speaker and Rules Committee:

the support of either the Speaker or a majority of the Rules Committee is required to ensure

floor consideration for a measure. Accordingly, while features such as the composition of

legislative committees,7 the rules granted to their proposals,8 and the assignment of members to various positions of power (e.g., committee and subcommittee chairs, party leaders

and whips)9 are clearly important, the composition of the House outside of the Speaker and

the Rules Committee can affect what reaches the House’s day-to-day legislative agenda only

through de facto forms of authority.10

The paper proceeds as follows. In the next section, I describe the details of the House’s

discharge process. Then I formally demonstrate the paper’s main result, after which I apply

the paper’s findings to a one-dimensional spatial model. In Section 5, I discuss an alternative justification for the paper’s main result, based on House precedent rather than on

the standing rules, per se. I then conclude with a discussion of the implications of the paper’s findings and a brief discussion of an illustrative and successful discharge attempt in

the 103rd Congress.

7

The literature on this topic is enormous. A few examples are Krehbiel (1990), Hall and Grofman (1990),

Groseclose (1994), Maltzman (1995, 1998), Adler and Lapinski (1997), Kollman (1997), Deering and Smith

(1997), Groseclose and Stewart III (1998), Overby and Kazee (2000), Frisch and Kelly (2004), and Parker et al.

(2004).

8

In addition to Dion and Huber (1996, 1997), and Krehbiel (1997), see, for example, Shepsle and Weingast

(1984), Gilligan and Krehbiel (1989a), Sinclair (1994), Evans (1999), and Hixon and Marshall (2002).

9

See, for example, Loomis (1984), Clausen and Wilcox (1987), Canon (1989), Rohde (1991), Sinclair (1995),

and Posler and Rhodes (1997).

10

For a formal discussion of the distinction between forms of authority in strategic situations, see Aghion

and Tirole (1997).

4

2 A Description of Discharge

With very few exceptions, every measure introduced in the House of Representatives is referred to at least one committee. After referral, a measure can be considered by the House

only after the committee(s) to which it has been referred have reported the measure back to

the floor or have been discharged from its consideration. Technically speaking, a committee can be discharged in a variety of ways, the most important of which are (1) unanimous

consent, (2) suspension of the rules, (3) enactment of a special rule reported from the Rules

Committee, (4) expiration of time limit imposed on the committee by the Speaker, or (5)

passage of a discharge motion.11

All methods of discharge except the last – a discharge motion – are controlled by the

House leadership. Both unanimous consent and suspension of the rules are limited in applicability, require supermajority approval, and are at the discretion of the Speaker. Use of a

special rule requires the consent of a majority of the Rules Committee. The right to impose

time limits on referral to a committee is absolute and held solely by the Speaker (Rule XII,

clause 2(c)(5)). Accordingly, if a measure that is opposed by both the Speaker and a majority of the Rules Committee membership is to receive floor action, it must be brought up

for consideration through the discharge procedure as set forth in House Rule XV. Given the

focus of this paper and in order to simplify exposition, I refer to application of this rule as

“the discharge process” for the remainder of the paper.

The Discharge Petition. The discharge process involves the filing of a discharge petition

by a member of the House.12 This petition can then be signed by House members at any

time during any legislative day until the end of Congress or until the petition is signed by

11

Rich descriptions of the discharge process are presented in Beth (2003a,b).

The motion to discharge a committee is always available, but is privileged only if the motion is placed

on the Calendar to Discharge Committees, which requires a successful discharge petition. In general, any

discharge motion “from the floor” is recognized only under unanimous consent.

12

5

218 members. Until 1993, signatures on the discharge petition were secret until the required

number had been reached, at which point the names were published in the Journal. This

secrecy was removed in 1993 by H.Res. 134, which amended clause 3 of Rule XXVII of the

House Rules to require that the Clerk “make the signatures a matter of public record.” This

change in the rules was itself effected by use of the discharge petition.13

There are (at least) three important features of the modern-day discharge process: (1)

how the procedure is applied to the Rules Committee versus how it is applied to legislative

committees, (2) limitations on what types of matters committees can be discharged from,

and (3) the scheduling of successful petitions for floor consideration. Below, I focus on the

first of these features and offer an abbreviated description of the second and third to the

degree that they play a role in the paper’s analysis.

2.1 Two Roads to the Floor

According to Rule XV, any member may file a petition to discharge

“(A) a committee from consideration of a public bill or public resolution that

has been referred to it for 30 legislative days; or (B) the Committee on Rules from

consideration of a resolution that has been referred to it for seven legislative

days and that proposes a special order of business for the consideration of a

public bill or public resolution that has been reported by a standing committee

or has been referred to a standing committee for 30 legislative days.” (Rule XV,

clause 2(b)(1))

Thus, there are two routes to the floor through the discharge process: a member may attempt to bring legislation to the floor either by discharging the committee of original jurisdiction from consideration of the measure or by discharging a resolution from the Rules

13

Discharge petition 103-2, filed by Rep. Inhofe on May 27, 1993, entered onto Discharge Calendar on September 8, 1993, called up and approved on September 28, 1993 (Roll no. 458: 384 Yeas, 40 Nays, 1 Present).

6

Committee calling for the consideration of the measure. There are two principal differences

between the two approaches. The first of these regards how the discharge petition itself is

dealt with when it is brought off the Discharge Calendar. The second (and most frequently

noted) difference concerns how the measure will be considered on the floor after the discharge motion is approved.

Discharge of a Legislative Committee. If a committee other than the Rules Committee is

discharged from consideration, then an immediate motion to consider the measure is privileged.14 After this motion is offered and agreed to, the measure is then “considered immediately under the general rules of the House.” In other words, a measure that is brought to the

floor by discharging the legislative committee to which it was referred is then considered by

the House under an open rule.

Discharge of the Rules Committee. If the Rules Committee is discharged from the consideration of a resolution, that resolution is immediately considered.15 After a successful

vote on the resolution, the House then proceeds under the order of business as described

in the resolution.16 Discharging the Rules Committee therefore allows the use of a closed or

hybrid rule for a bill’s consideration.

2.2 Other Details about Discharge

Since a discharge petition is intended to discharge a committee from consideration of a

measure, once a measure has been reported by a committee, any petition calling for the

14

This motion is privileged so long as the motion is the next one offered and is offered by a member whose

signature appears on the discharge petition. If such a motion is not immediately offered, then the measure is

referred by the Speaker to the appropriate calendar. (Deschler, Ch 18 § 4.7)

15

The only intervening motion allowed is a single motion to adjourn.

16

If the resolution fails, the House returns to normal business and the possibility of discharging a substantially similar measure is precluded for the remainder of the session.

7

discharge of that committee from the consideration of that measure is moot. Even if the discharge petition has already been signed by 218 members, the petition can be circumvented

by the committee simply by reporting the measure and having it referred to the appropriate calendar (Deschler, Ch 18 § 1.11). In addition, preemptive reporting by a committee is

always possible: a discharge motion is a privileged matter only on the second and fourth

Mondays of the month and only after it has been on the Discharge Calendar for at least

seven legislative days.17

There are a few restrictions on what can be discharged, including the maximum number of bills that may be covered by a single petition (one), the number of times a motion to

discharge may deal with any given policy issue (once per session), and what may be the subject of a discharge motion (essentially only public bills and germane amendments). These

points are discussed briefly below.18

One Bill At A Time. A single discharge petition can discharge a committee from consideration from exactly one measure (or, in the case of discharging the Rules Committee, a single

petition can discharge a resolution calling for the consideration of a single measure). Furthermore, a special rule is subject to discharge only if it does not make in order any nongermane amendments. These restrictions were added in the 105th Congress (House Rules and

Manual Ch 19 § 3).19

17

Furthermore, this privilege disappears during the final six days of a session (Deschler, Ch 18 § 3.3).

It should be noted that these seemingly minor details, which are not the focus of the remainder of the

paper, have all been changed at least once since the discharge rule’s inception in 1910, suggesting that they

have been perceived by at least some members as strategically relevant.

19

Additionally, a strict reading of subparagraph (2) of Rule XV, clause 2(b) (“Only one motion may be presented for a bill or resolution.”) implies that each bill or resolution may be the subject of at most one petition.

Such an interpretation of this provision – which was added to the standing rules at the beginning of the 105th

Congress – would imply that the various means of circumventing discharge petitions discussed below would

be final in the sense that, upon circumvention of the first discharge petition, no other discharge petitions relating to the measure in question would be in order. While this interpretation has not been tested empirically

to my knowledge, the explicit inclusion of this statement in the rules and its intended effects are intriguing.

18

8

No Repetition. Once a discharge petition has been dealt with by the House, consideration

of a discharge motion dealing with a matter that is “substantially the same” is not in order

for the remainder of the session (Rule XV, clause 2(f)).

What May Be The Subject Of Discharge. A small class of legislative business, such as executive communications and the resolution of inquiries, are considered to be so important

as to be subject to discharge at any time through a (privileged) motion to discharge offered

from the floor. Some matters that are (or eventually become) automatically subject to discharge without the filing of a discharge petition include

1. Propositions to discipline a member and impeachment resolutions (Deschler, Ch 18

§ 5),

2. Vetoed bills that have been returned to House (Deschler, Ch 18 § 5.1), and

3. Budget recissions and impoundment resolutions (2 USC § 688).

Finally, some measures may not be the subject of a discharge petition: for example, private

bills and resolutions appointing a committee to investigate are excluded from the provisions

of Rule XV (Deschler, Ch 18 § 2.6).

3 Toward A Strategic Calculus of the Discharge Process

In this section, I demonstrate that, under the standing rules of the House, opposition of the

Speaker and a majority of the Rules Committee can circumvent any discharge motion. In

order to clarify the following discussion, I denote the bill in question by x, any special rule

(i.e., a resolution) calling for the consideration of x by r , the membership of the House by

N , the legislative committee to which x is referred by C ⊂ N , the Rules Committee by R ⊂ N ,

and the Speaker of the House by S ∈ N .

9

Assume now that x is supported by a majority of N . If the Speaker supports x, he or

she can ensure it comes up for a floor vote. As Speaker Tip O’Neill famously observed, “the

power of the Speaker of the House is the power of scheduling.” Similarly, if a majority of

the Rules Committee supports x, they can also ensure that it receives a floor vote through

its ability to originate, and report at any time, measures dealing with the order of business

within the House.

The only case in question, then, is whether simultaneous opposition by a majority of the

Rules Committee and the Speaker is sufficient to stymie floor consideration of x. While there

are a number of ways in which such obstruction might be accomplished,20 the simplest

way involves the Speaker using his or her power to set time limits on committees, thereby

removing x (or any corresponding rule r ) from committee and, accordingly, making any

attempts to apply the discharge procedure to x (or r ) moot.

Using Time Limits to Avoid Discharge. If the Speaker opposes x, he or she can set a time

limit on the committee that is the subject of the discharge petition (either C or R) such that,

prior to the discharge motion becoming privileged, the committee in question is discharged

from the consideration of x (or r , if the discharge petition is aimed at R). The Speaker’s

power to set such time limits does not depend on whether the measure in question was referred primarily, initially, or sequentially, or the committee to which the measure is referred

(Brown and Johnson (2003) Ch 6 § 11). Consideration of a measure discharged by the expiration of a time limit is, in general, not a privileged matter, even if the measure’s consideration

would have been a privileged matter if reported from the committee in question. This is

because, in the typical sense of privileged business, measures inherit their privilege from

the committee’s report on the measure. If a committee is discharged by expiration of a time

limit, there is no report from the committee and, accordingly, no privilege for the measure

20

One of the most nefarious of these is discussed below in Section 5.

10

to inherit.

Given this fact, securing floor action on x after C (or R) is discharged from its consideration would require the filing of a privileged report by the Rules Committee calling for the

consideration of x, which requires the support of a majority of R. Accordingly, if the Speaker

and a majority of the Rules Committee oppose a measure, they can (ironically) circumvent

a discharge petition in favor of that measure by agreeing to place the measure (and any resolution(s) calling for its consideration) on the appropriate calendar.

3.1 Decisive Coalitions and the Discharge Process

A decisive coalition is any subset of the membership, D ⊆ N , such that, for any pair of policies x and y, x ºi y for all i ∈ D implies that x will be chosen over y by the House. Let D

denote the set of decisive coalitions in the House. According to Krehbiel’s definition, the

House is majoritarian only if D contains all subsets with at least 218 members.21

Clearly, in order to be decisive for x, a coalition must be able to obtain a floor vote on

x. Accordingly, the analysis above implies that a coalition of legislators, D, is a decisive

coalition (D ∈ D) under the standing rules of the House only if

1. D is a majority coalition and

2. D contains either the Speaker or a majority of the Rules Committee.

Since there are majority coalitions that do not satisfy condition (2), the standing rules of

the House are not majoritarian. The ultimate effect of a discharge motion for a majority

supported bill x, as a function of the Speaker’s preferences, the majority preference of the

21

For any set D, |D| denotes the cardinality of (i.e., number of elements in) D. The definition of decisive

coalitions when members may be absent or abstain is slightly cumbersome and adds no additional insight for

the point of this paper. This leads to the requirement that D contain the set of all coalitions with at least 218

members. If we assume that all members always vote, then the standing rules of the House satisfy Krehbiel’s

definition of a majoritarian institution if and only if D = {D ⊆ N : |D| ≥ 218}.

11

legislative committee to which x is referred, and the majority preference of the Rules Committee, is displayed in Table 1. (All cells in Table 1 would contain “Bill is Approved” if the

standing rules of the House were majoritarian.)

[Table 1 Here.]

Before continuing, it is useful to recall the three key facts on which the analysis is based:

1. a discharge motion is moot if no committee has jurisdiction over the measure when

the motion is offered,

2. through his or her power to set time limits, the Speaker can effectively discharge any

measure from any committee, and

3. a resolution calling for the consideration of a measure (i.e., a “special order”) is privileged only if it is reported by the Rules Committee.

4 The Discharge Petition and Policy Outcomes

Given the fact that policy change requires obtaining a floor vote, the realities of the discharge

process described above change the calculation of the pivotal member of the House. Let X

be a set of policies, with q ∈ X denoting the status quo policy, and denote the (complete and

transitive) preference relation of each member i by ºi . Then, for any member i and any

policy z ∈ X , the set of policies (weakly) preferred by i to z is denoted by

Wi (z) = {x ∈ X : x ºi z},

and

¡

¢

W (q) = ∪µ∈{d ⊂N :|d |≥218} ∩i ∈µWi (q)

12

denotes the usual majority rule “winset” of q: the set of policies that at least 218 of the

members weakly prefer to q.

In a pure majoritarian world, policy change is predicted to occur whenever W (q) is nonempty. However, in order for a bill x to defeat the status quo, q, it must be preferred by

the Speaker, S, or a majority of the Rules Committee, R. The set of policies that satisfy this

requirement, given the status quo q, is denoted by D(q), which is formally defined as

D(q) ≡ WS (q) ∪

o

n

ρ∈ d ⊆R:|d |> |R|

2

£

¤

∩i ∈ρ Wi (q) .

(1)

For any policy x 6∈ D(q) as defined in (1), the Speaker and R will keep x from being considered on the floor. Accordingly, the standing rules of the House imply that the set of policies

that will receive a floor vote and defeat the status quo q is defined as follows:

DW(q) = D(q) ∩ W (q).

(2)

Before continuing, it is interesting to note that the legislative committee, C , plays no

role in (2). This presentation assumes for simplicity that the discharge petition calls for the

discharge of the Rules Committee from consideration of a special rule for the consideration

of the bill in question, rather than directly discharging C from the bill itself. In addition,

while the presentation seems to imply that a majority of the members of C oppose the bill,

the calculation of D(q) is not conditional upon (i.e., does not require) this assumption: if

a majority of the members of C support reporting the bill to the floor, then as described

above, the Speaker can simply discharge C from the bill’s consideration. In other words, the

Speaker’s opposition to a bill is sufficient to ensure that the bill is not under the jurisdiction

of a committee in which the bill has majority support.22

22

This is also consistent with the predictions presented in Table 1.

13

The Unidimensional Spatial Model. Now consider a unidimensional spatial model of the

House with symmetric, single-peaked policy preferences, as utilized by Krehbiel (1998) and

many others. Let f denote the location of the median members of the House’s ideal point,

R m denote the location of the median member of the Rules Committee’s ideal point,23 and

S denote the Speaker’s ideal point. The above definition of DW(q) implies that the pivotal

member of the House is the player with the median ideal point among f , R m , and S. In

effect, the decision about whether to allow floor action on a measure is a majority rule game

between f , R m , and S in which f always votes “yes,” because the floor median realizes that

he or she can not be made worse off by having a measure be considered on the floor. In this

unidimensional world, successful obstruction of floor action occurs if the ideal points of the

median member of the Rules Committee and the Speaker are on the same side of the status

quo policy and the floor’s median ideal point is on the opposite side of the status quo policy,

q. The set of policies that defeat the status quo, DW (q), is illustrated for several preference

profiles in Figure 1.

[Figure 1 Here.]

Figure 1 presumes that q < f and R m < S. The top scenario in Figure 1, Line (1), represents the baseline of a majoritarian institution by omitting S and R m . The shaded region,

W (q), represents the set of policies that will defeat the status quo if proposed. Lines (2)-(6)

display the modified winset, DW (q), as the ideal points of the median member of the Rules

Committee and the Speaker are moved closer to the status quo. On Lines (2) and (3), at least

one of these members desires policy change in the same direction as, and by a larger magnitude than, the floor’s median voter, implying that DQ(q) = W (q). On Lines (4) and (5), at

least one of those members desire policy change in the same direction as, but by a smaller

23

For simplicitly, I will assume that the Rules Committee has an odd number of members, so that R m is

unique.

14

amount than, the floor’s median voter. Accordingly, DW (q) ⊂ W (q), so that some proposals

in W (q) would not reach the floor, but some form of policy change will occur. Finally, Line

(6) displays a situation in which no proposal will reach the floor: the floor’s median voter

disagrees with both the Speaker and the median member of the Rules committee about the

direction of policy change, so that DW (q) = q.

The prerogatives of the Speaker and Rules Committee utilized in the above analysis are

explicitly stated in the standing rules of the House. Because of its theoretical and historical

interest, the next section discusses an alternative means – based on House precedent rather

than the standing rules, per se, by which the Rules Committee could stymie an attempt to

discharge it from the consideration of a resolution.

5 Another Way to Sidestep Discharge

In theory, the Rules Committee and Speaker could nullify a discharge petition using an alternative route. In particular, House precedent states that a discharge petition is attached

to the number and title of the bill as referred to in the petition, not the text of the bill at

the time the discharge petition is filed (Deschler, Ch 18 § 1.13). This precedent was set by

Speaker Rainey in the 78th Congress. The ruling followed a strange sequence of events surrounding a piece of banking legislation. The matter, H.R. 7908, had been reported by the

Committee on Banking and Currency on April 12, 1934. The discharge petition received the

requisite number of signatures the next day, April 13. However, on April 20, Speaker Rainey

ruled that the measure had not been validly reported by the committee because the motion

to report had been approved by the committee while the House was in session. Following

this decision, the committee substituted the text of H.R. 9175 for the text of H.R. 7908 and

reported the amended measure – again, numbered as H.R. 7908 – to the floor on April 23.

On that same day, Speaker Rainey ruled an attempt to discharge the Committee on Banking

15

and Currency from consideration of H.R. 7908 out of order. Furthermore, he ruled that the

discharge motion was tied to the number and title of the bill rather than the substance of

the measure.

“. . . The only thing the Chair knows is that the McLeod bill, bearing the number it has always borne and with the same title, and with some amendments

in which the Chair is not interested, has been reported out, is on the calendar,

and can be taken up under the general rules of the House when an opportunity

presents itself. The Chair overrules the point of order.”

Thus, in theory, the precedent set by Speaker Rainey in 1934 implies that the Rules Committee could amend the special rule, r , so that it no longer calls for the consideration of x

(nullifying the desired effect of r ) and then report the amended rule to the floor with the

same title and number as when it was referred to the Rules Committee. The analysis presented earlier does not rely on this maneuver because it is based on a precedent set in a

Congress in which the discharge petition required less than a majority (the required number in the 78th Congress was 145). Accordingly, it is plausible that this tactic (if challenged

through a point of order) would not now be upheld by a majority vote of the membership of

the House.

6 What Does Discharge Do?

This paper has offered a direct and succinct theory of the discharge process in the US House

of Representatives. The motivation of this examination is to provide a more solid procedural

basis for distinction between the various theories of Congressional organization and behavior. Several scholars have argued that the rules of the House are fundamentally majoritarian

in the sense that any majority of the House membership is decisive in determining pol-

16

icy outcomes. Recognizing the supermajoritarian features of the normal process by which

legislation flows through the House, these scholars tend to point to the discharge process

as the safety valve through which any majority-supported piece legislation may flow. The

result presented here implies that, at least in de jure terms, this conclusion is suspect. Moreover, far from being a majoritarian safety valve, the discharge process itself is superfluous:

a successful discharge petition must obtain (at least implicit) endorsement from either the

Speaker or a majority of the Rules Committee. As pointed out in Section 2, such endorsement is sufficient to secure floor access through one of several more commonly observed

routes to the floor, such as a special order reported from the Rules Committee or through

suspension of the rules as recognized by the Speaker of the House.

Viewed broadly, the paper’s result suggests that the relative rarity of discharge petitions

is not necessarily indicative of an equilibrium effect in which the credible possibility of discharge is sufficient to eliminate obstruction by the House leadership. Rather, the analysis

suggests that the discharge process may be effective on occasion precisely because its use is

costly and the act of signing a discharge petition is thereby possibly informative. This raises

interesting questions about the effect of the 1993 rule change that led to petition signatures

being made public. It is not clear what effect the publication of signatures has on the informativeness of the act of signing. For example, while removing one’s signature is now

presumably more costly, the act of signing itself may now be driven by perceived electoral

rewards instead oa sincere desire to have the measure enacted by the House. As both opponents and proponents of the rule change pointed out during the debate in 1993, publishing

the discharge signatures makes the act of signing a discharge petition essentially equivalent

to cosponsoring a measure. The exact effect of this rule change in the 103rd Congress represents an interesting avenue for future work on the agenda-setting process within the House.

In addition, the process by which the rule change was effected in some sense an illustration

of the main point of this paper. Before concluding, I briefly describe the fight preceding,

17

and final roll call vote concerning, the rule change.

An Example: Making The Discharge Petition Public. As described earlier, the House Rules

now provide that the signatures on discharge petitions are to be made public each week.

The proposal for this rule change in the 103rd Congress was contained in H.Res. 134, introduced by Rep. Jim Inhofe (R, OK) and referred to the Rules Committee on March 18,

1993. Rep. Porter Goss (R, FL), a minority member of the Rules Committee, added himself as a cosponsor on March 29, 1993.The rhetoric surrounding H.Res. 134 was heated and

partisan: the proposal was opposed by the Democratic leadership and Rep. Inhofe filed a

discharge petition on May 27, 1993. The 218th signature was recorded on September 8, 1993

and the Rules Committee was discharged by unanimous consent on September 24th. Every

Republican member of the Rules Committee (Reps. Dreier, Goss, Quillen, and Solomon)

signed the petition. The resolution was voted upon on Sept 28th, and passed by a vote of

384-40. Not surprisingly, all 40 members who opposed the measure were Democrats. Interestingly, however, only one member of the Rules Committee voted against the resolution

(Rep. Moakley, the chair of the committee): every other member of the Rules Committee

and Democratic leadership voted in favor of the rule change, including Rep. Gephardt and

Rep. Bonior (D. MI), the majority leader and whip, respectively. Including Moakley, eight of

the members who voted against the resolution were committee chairmen.

Even though the final vote in September 1993 was quite lopsided, the fight leading up to

the resolution’s passage was protracted: at least six members removed their names from the

petition as the result of pressure from Rep. Moakley. One of these members, Rep. Tony Hall

(D, OH), was a member of the Rules Committee (Jacoby (1993f)). All six of these members

eventually voted in favor of the resolution. In addition to direct lobbying by Rep. Moakley,

there was active bargaining prior to enactment of H.Res. 134, ranging from a compromise

proposal, offered by Rep. Moakley, that would give committees 30 days to consider legis-

18

lation after the 218 signatures had been collected (Jacoby (1993d)) to more minute details,

such as whether it would be applied retroactively to two other discharge petitions – concerning term limits and the line-item veto – that were active at the time Inhofe’s petition

obtained 218 signatures.24 Throughout this process, Moakley and other critics of the proposal argued that H.Res. 134 was unnecessary, as the Joint Committee on the Organization

of Congress was considering the issue within a broader reform agenda at the time (Pinkus

(1993)). Indeed, even after the petition obtained 218 signatures, the Rules Committee held

hearings on the issue and at least briefly considered procedural means of thwarting (or at

least modifying) the proposal (Jacoby (1993a)).

Ultimately, Democratic leaders conceded in early September that the rule change would

pass, with Rep. Moakley ultimately encouraging Democratic freshmen, whom Inhofe had

been especially active in recruiting for signatures, to sign the petition if doing so would help

them in their home districts (Jacoby (1993e)). Providing electoral cover for members who

did not sign Inhofe’s petition was also the Democratic leadership’s justification for recording

a vote on the resolution (Cooper (1993)). In the end, since every member of the Rules Committee, save Chairman Moakley, voted in favor of the resolution, it is highly unlikely that

an attempt to circumvent the discharge petition, as described above, would have ultimately

had the support of a majority of the Rules Committee’s members. Furthermore, if the Rules

Committee members’ votes were not sincere, the experience surrounding H.Res 134 in the

103rd Congress serves as a useful illustration of the distinction between de jure and de facto

majoritarianism, a distinction that I now turn to in an attempt to place the paper’s findings

within broader debates concerning political institutions and behavior.

24

Initially, the rule change was not to be applied retroactively (Jacoby (1993b)). However, Reps. Moakley and

Inhofe agreed to reverse this position the night before the vote (Jacoby (1993c)). It is unclear why they agreed

to make this change.

19

De Facto vs. De Jure Gatekeeping and Institutional Analysis. Clearly, the analysis here

challenges strict majoritarian interpretations of House policymaking. A reasonable counterargument in favor of House policymaking being majoritarian would rely upon a de facto

justification. According to such an argument, the Speaker and Rules Committee would not

oppose a majority supported discharge petition with the procedural maneuvers described

here. Indeed, one could attempt to fashion such an argument based upon the fact that the

Speaker serves at the pleasure of the House and, according to a precedent set by Speaker

Cannon, the motion to replace the Speaker carries the highest privilege. Similarly, the House

could reassign memberships on the Rules Committee, change the jurisdictions of standing

committees, or even revise or reject the standing rules of the House. However, such arguments are not without their own risks. In particular, the last three decades of Congressional

scholarship has produced great progress within an institutional/game theoretic framework.

A basic supposition of this framework is that, at the end of the day, the “rules of the game”

are indeed the rules of the game. The analysis presented here has taken the standing rules

of the House as exactly that and shown that, under these (majority-approved) rules, the

Speaker and the Rules Committee possess negative agenda control in a de jure sense. Arguing that the standing rules of the House are not themselves binding on the membership

is a slippery slope. Essentially, disregarding the possibility for circumventing discharge as

described in this paper based on the supposition that the membership of the House will,

for example, replace the Speaker or Rules Committee if the procedures described here are

utilized, should force one to also deal explicitly with other theoretically inconvenient but,

strictly speaking, purely majoritarian possibilities, such as the ability of the floor to overrule

the House’s famous requirement that amendments be germane.

Of course, as mentioned in the introduction of the paper, the practice of the House is

that the membership chooses its standing rules at the beginning of each Congress. This

choice is governed by simple majority rule. Indeed, aside from the Speaker, the only true

20

leadership positions that exist prior to the adoption of the standing rules are those of the

two parties: no committees exist prior to the adoption of the standing rules. Accordingly,

the non-majoritarian nature of bill scheduling under the standing rules has received explicit

majority approval at the beginning of each Congress since 1910. Perhaps more of our focus

should be placed on the reasons that the majority of the House membership consistently

chooses standing rules that apparently restrict the later ability of a majority to influence the

legislative agenda and, accordingly, policy outcomes.

In conclusion, the description by Krehbiel (1991) and Crombez et al. (2006) of the House

as a majoritarian institution is undoubtedly correct in at least one sense: when the House

first convenes, any majority of its membership can dictate the standing rules. Nevertheless,

since 1910, a majority of the House membership have consistently approved standing rules

that restrict the set of majority coalitions that can control the legislative agenda. Thus, a

complete understanding of the US House of Representatives must include an explanation

for majority preference for seemingly non-majoritarian procedures.

References

Adler, E. S. and Lapinski, J. S. (1997). Demand-Side Theory and Congressional Committee

Composition: A Constituency Characteristics Approach. American Journal of Political

Science, 41(3):895–918.

Aghion, P. and Tirole, J. (1997). Formal and Real Authority in Organizations. Journal of

Political Economy, 105(1):1–29.

Aldrich, J. H. (1994). A Model of a Legislature with Two Parties and a Committee System.

Legislative Studies Quarterly, 19(3):313–339.

Aldrich, J. H. (1995). Why Parties? The Origin and Transformation of Political Parties in

America. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL.

Aldrich, J. H. and Rohde, D. W. (2000). The Republican Revolution and the House Appropriations Committee. Journal of Politics, 62:1–33.

Aldrich, J. H. and Rohde, D. W. (2004). Congressional committees in a partisan era. In Dodd,

21

L. C. and Oppenheimer, B. I., editors, Congress Reconsidered, pages 249–270. CQ Press,

Washington, D.C., 8th edition.

Beth, R. S. (2003a). The Discharge Rule in the House: Principal Features and Uses. Congressional Research Service Report 97-552.

Beth, R. S. (2003b). The Discharge Rule in the House: Recent Use in Historical Context.

Congressional Research Service Report 97-856.

Binder, S. A., Lawrence, E. D., and Maltzman, F. (1999). Uncovering the Hidden Effect of

Party. Journal of Politics, 61(3):815–831.

Brown, W. H. and Johnson, C. W. (2003). House Practice: A Guide to the Rules, Precedents,

and Procedures of the House. US Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

Burden, B. C. (2004). The Discharge Rule and Majoritarian Politics in the U.S. House of

Representatives. Mimeo, Harvard University.

Burden, B. C. (2005). The Discharge Rule and Minority Rights in the U.S. House of Representatives. Mimeo, Harvard University.

Canon, D. T. (1989). The Institutionalization of Leadership in the U. S. Congress. Legislative

Studies Quarterly, 14(3):415–443.

Clausen, A. R. and Wilcox, C. (1987). Policy Partisanship in Legislative Leadership Recruitment and Behavior. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 12(2):243–263.

Cooper, K. J. (1993). House Moves to Reduce Secrecy. Roll Call, September 29.

Cox, G. and McCubbins, M. D. (1997). Toward a Theory of Legislative Rules Changes: Assessing Schickler and RichŠs Evidence. American Journal of Political Science, 41:1376–1389.

Cox, G. W. and McCubbins, M. D. (1993). Legislative Leviathan: Party Government in the

House. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA.

Cox, G. W. and McCubbins, M. D. (2005a). Setting the Agenda: Responsible Party Government

in the U.S. House of Representatives. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA.

Cox, G. W. and McCubbins, M. D. (2005b). Setting the Agenda: Responsible Party Government

in the U.S. House of Representatives. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA.

Crombez, C., Groseclose, T., and Krehbiel, K. (2006). Gatekeeping. Journal of Politics, 68(2).

Deering, C. J. and Smith, S. S. (1997). Committees in Congress. CQ Press, Washington, DC,

3rd edition.

Dion, D. and Huber, J. (1996). Party Leadership and Procedural Choice in Legislatures. Journal of Politics, 58:25–53.

22

Dion, D. and Huber, J. (1997). Sense and Sensibility: The Role of Rules. American Journal of

Political Science, 41:945–957.

Evans, C. L. (1999). Legislative Structure: Rules, Precedents, and Jurisdictions. Legislative

Studies Quarterly, 24(4):605–642.

Frisch, S. A. and Kelly, S. Q. (2004). Self-Selection Reconsidered: House Committee Assignment Requests and Constituency Characteristics. Political Research Quarterly, 57(2):325–

336.

Gilligan, T. and Krehbiel, K. (1987). Collective Decision-Making and Standing Committees:

An Informational Rationale for Restrictive Amendment Procedures. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 3:287–335.

Gilligan, T. and Krehbiel, K. (1989a). Asymmetric Information and Legislative Rules with a

Heterogeneous Committee. American Journal of Political Science, 33:295–314.

Gilligan, T. W. and Krehbiel, K. (1989b). Collective Choice without Procedural Commitment.

In Ordeshook, P. C., editor, Models of Strategic Choice in Politics. University of Michigan

Press, Ann Arbor, MI.

Groseclose, T. (1994). Testing Committee Composition Hypotheses for the U.S. Congress.

Journal of Politics, 56(2):440–458.

Groseclose, T. and Stewart III, C. (1998). The Value of Committee Seats in the House, 194791. American Journal of Political Science, 42(2):453–474.

Hall, R. L. and Grofman, B. (1990). The Committee Assignment Process and the Conditional

Nature of Committee Bias. American Political Science Review, 84(4):1149–1166.

Hixon, W. and Marshall, B. W. (2002). Examining Claims about Procedural Choice: The Use

of Floor Waivers in the U.S. House. Political Research Quarterly, 55(4):923–938.

Jacoby, M. (1993a). Discharge Bill May Be Gutted: Rules Plots Strategy. Roll Call, September

13.

Jacoby, M. (1993b). Discharge Petition Rule Will Not Apply to Term Limits or Line-Item Veto.

Roll Call, September 27.

Jacoby, M. (1993c). Discharge Rule Will Apply To Old Petitions. Roll Call, September 30.

Jacoby, M. (1993d). House Leaders Can’t Agree On Discharge Compromise. Roll Call, September 16.

Jacoby, M. (1993e). Inhofe’s Discharge Petition Bill Set Free From Rules After 218 Members

Sign On. Roll Call, September 9.

23

Jacoby, M. (1993f). Untitled. Roll Call, September 6.

Kollman, K. (1997). Inviting Friends to Lobby: Interest Groups, Ideological Bias, and Congressional Committees. American Journal of Political Science, 41(2):519–544.

Krehbiel, K. (1990). Are Congressional Committees Composed of Preference Outliers? American Political Science Review, 84(1):149–163.

Krehbiel, K. (1991). Information and Legislative Organization. University of Michigan Press,

Ann Arbor, MI.

Krehbiel, K. (1995). Cosponsors and Wafflers from A to Z . American Journal of Political

Science, 39(4):906–923.

Krehbiel, K. (1997). Restrictive Rules Reconsidered. American Journal of Political Science,

41(3):919–944.

Krehbiel, K. (1998). Pivotal Politics: A Theory of U.S. Lawmaking. University of Chicago

Press, Chicago, IL.

Krehbiel, K. (1999). Paradoxes of Parties in Congress. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 24:31–64.

Krehbiel, K., Shepsle, K. A., and Weingast, B. R. (1987). Why Are Congressional Committees

Powerful? American Political Science Review, 81(3):929–945.

Lindstadt, R. and Martin, A. D. (2003). Discharge Petition Bargaining in the House, 19952000. Mimeo, Washington University.

Loomis, B. A. (1984). Congressional Careers and Party Leadership in the Contemporary

House of Representatives. American Journal of Political Science, 28(1):180–202.

Maltzman, F. (1995). Meeting Competing Demands: Committee Performance in the Postreform House. American Journal of Political Science, 39(3):653–682.

Maltzman, F. (1998). Maintaining Congressional Committees: Sources of Member Support.

Legislative Studies Quarterly, 23(2):197–218.

Martin, A. D. and Wolbrecht, C. (2000). Partisanship and Pre-Floor Behavior: The Equal

Rights and School Prayer Amendments . Political Research Quarterly, 53(4):711–730.

Oleszek, W. J. (2001). Congressional Procedures and the Policy Process. CQ Press, Washington,

DC, 5th edition.

Overby, L. M. and Kazee, T. A. (2000). Outlying Committees in the Statehouse: An Examination of the Prevalence of Committee Outliers in State Legislatures. Journal of Politics,

62(3):701–728.

24

Parker, G. R., Parker, S. L., Copa, J. C., and Lawhorn, M. D. (2004). The Question of Committee Bias Revisited. Political Research Quarterly, 57(3):431–440.

Peabody, R. (1985). House Party Leadership: Stability and Change. In Dodd, L. C. and Oppenheimer, B., editors, Congress Reconsidered. CQ Press, Washington, DC, 3rd edition.

Pinkus, M. (1993). Discharge Petitions Give Members Time For Second Thoughts. Roll Call,

September 6.

Posler, B. D. and Rhodes, C. M. (1997). Pre-Leadership Signaling in the U. S. House. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 22(3):351–368.

Rohde, D. W. (1991). Parties and Leaders in the Postreform House. University of Chicago

Press, Chicago, IL.

Rohde, D. W. (1994). Parties and Committees in the House: Member Motivations, Issues,

and Institutional Arrangements. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 19(3):341–359.

Schickler, E. (2000). Institutional Change in the House of Representatives, 1867-1998: A Test

of Partisan and Ideological Power Balance Models. American Political Science Review,

94:267–88.

Schickler, E. (2002). Disjointed Pluralism: Institutional Innovation and the Development of

the U.S. Congress. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Schickler, E. and Rich, A. (1997a). Controlling the Floor: Parties as Procedural Coalitions in

the House. American Journal of Political Science, 41:1340–1375.

Schickler, E. and Rich, A. (1997b). Party Government in the House Reconsidered: A Response

to Cox and McCubbins. American Journal of Political Science, 41:1387–1394.

Shepsle, K. A. (1979). Institutional Arrangements and Equilibrium in Multidimensional Voting Models. American Journal of Political Science, 23(1):27–59.

Shepsle, K. A. and Weingast, B. R. (1982). Institutionalizing Majority Rule: A Social Choice

Theory with Policy Implications. American Economic Review, 72(2):367–371.

Shepsle, K. A. and Weingast, B. R. (1984). When Do Rules of Procedure Matter? Journal of

Politics, 46(1):206–221.

Sinclair, B. (1994). House Special Rules and the Institutional Design Controversy. Legislative

Studies Quarterly, 19(4):477–494.

Sinclair, B. (1995). Legislators, Leaders, and Lawmaking: The U.S. House of Representatives

in the Postreform Era. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

25

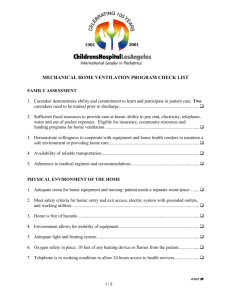

Table 1: Scenarios & Outcomes for A Majority Supported Bill

S Opposes

Majority of

C Opposes

Majority of R Opposes

S Supports

Majority of

C Supports

Bill Dies

Majority of R Supports

Majority of

C Opposes

Bill is Approved

Bill is Approved

C : Legislative Committee, R: Rules Committee, S: Speaker

26

Majority of

C Supports

Figure 1: Unidimensional Discharge Scenarios

Majoritarian Institution

W(q)

(1)

q

f

Gates Opened: Roll Call Vote Observed

DW(q)=W(q)

(2)

q

f

Rm

S

DW(q)=W(q)

(3)

q

Rm

f

S

DW(q) ⊂ W(q)

(4)

q

Rm

S

f

DW(q) ⊂ W(q)

(5)

Rm

q

S

f

Gates Closed: No Roll Call Vote

DW(q)=q

(6)

Rm

S

q

f

Legend

q :

f :

Rm:

S :

Status Quo Policy

Median Ideal Point of the Floor

Median Ideal Point of the Rules Committee

Speaker’s Ideal Point

27