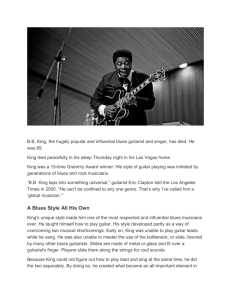

Sixties Blues and Psychedelia

advertisement