Teaching Materials - Center for the Humanities

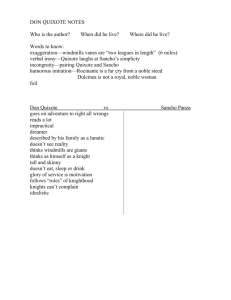

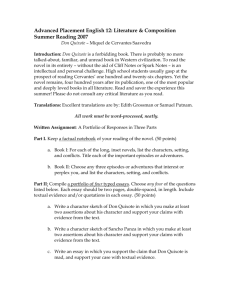

advertisement