Proportionality Principle - Its Sources and Meaning Today: Harmelin

advertisement

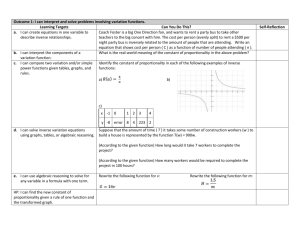

1249 THE PROPORTIONALITY PRINCIPLE---ITS SOURCES AND MEANING TODAY: HARMELIN V. MICHIGAN AND ITS PRECEDENT INTRODUCTION The United States Supreme Court and legal commentators have long battled over the substantive content of the baldly-worded "cruel and unusual punishment" clause of the eighth amendment.' One focal point of this debate is the question of the existence of and the appropriate constitutional weight to be given the proportionality principle.2 The proportionality principle requires that the criminal sentence imposed be proportionate to the severity of the crime 3 committed. The Court recently decided Harmelin v. Michigan,4 in which Justice Scalia, in a concurrence joined solely by Chief Justice Rehnquist, found that the eighth amendment does not contain a proportionality principle. 5 Justice Scalia declared that the Court's eightyear-old decision in Solem v. Helm, 6 which held that the eighth amendment contains a broad proportionality guarantee, should be overruled. 7 Justice Scalia's concurrence did not end the debate however, as three members of the Court in a second concurrence and four members in the dissent found that the eighth amendment does contain a proportionality principle. 8 This Comment focuses generally on the proportionality principle in noncapital sentencing cases and addresses the Court's capital sen1. See, e.g., Weems v. U.S., 217 U.S. 349, 368-69 (1910) (reviewing the history and precedent of the clause and disagreeing with a legal commentator who argued that the clause only admonishes the government to proscribe tortuous punishments of the Stuarts); O'Neil v. Vermont, 144 U.S. 323 (1892) (Field, J., dissenting) (arguing that the cruel and unusual punishment clause prohibits tortuous punishments and punishments found disproportionate due to excessive length or severity); Note, 24 HARV. L. REV. 54 (1910) (arguing that the Weems' Court's progressive construction of the cruel and unusual punishment clause, which found the clause to prohibit excessive punishments, was desirable). 2. See infra notes 4-8, 19-31 and accompanying text. 3. 24 C.J.S. Criminal Law § 1594 (1989). 4. 111 S. Ct. 2680 (1991). 5. Id. at 2686 (Scalia, J., concurring). 6. 463 U.S. 277 (1983). 7. Harmelin, 111 S. Ct. at 2686; Solem, 463 U.S. at 284. 8. Harmelin, 111 S. Ct. at 2702 (Kennedy, J., concurring); Id. at 2709 (White, J., dissenting). Justice Kennedy, concurring in part and concurring in the judgment, was joined by Justices O'Connor and Souter. Id. at 2702 (Kennedy, J., concurring). Justice White dissented and was joined by Justices Blackmun and Stevens. Id. at 2709 (White, J., dissenting). Justice Marshall agreed with the dissent and also authored a separate dissenting opinion. Id. at 2719 (Marshall, J., dissenting). 1250 CREIGHTON LAW REVIEW [Vol. 25 tencing decisions as these decisions impact the proportionality debate. 9 This Comment first examines the debate over the historical origins of the proportionality principle.' 0 This Comment then follows the development of eighth amendment interpretation in Supreme Court decisionmaking." The reasoning in four recent Supreme Court decisions illuminates the disagreement among members of the Court regarding the proportionality principle.' 2 This Comment focuses on Harmelin and evaluates the difficulty the Court has had in agreeing on the appropriate constitutional weight of the proportionality principle.' 3 Next, this Comment briefly discusses the division of the lower courts applying the proportionality principle after Harmelin."4 This Comment then analyzes the two conflicting modes of eighth amendment interpretation used in the Harmelin decision. 15 The two modes are the textual and historical analysis, and an "evolving standard" analysis.' 6 This Comment concludes that the "evolving standard" is more ethical in its result and more sound in its 17 reasoning than pure textual and historical interpretation. BACKGROUND THE HISTORICAL ORIGINS OF THE CRUEL AND UNUSUAL PUNISHMENT CLAUSE The eighth amendment, applied to the states through the due process clause of the fourteenth amendment, provides: "Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted."' 8 Legal commentators, using textual and historical analysis, differ as to the meaning of the cruel and unusual punishment clause and particularly to the existence of a proportionality principle, which demands that the punishment imposed must be proportionate to the crime committed.' 9 Some commentators have adopted the "traditional view," that the clause prohibits only barbarous forms of punishment, as opposed to prohibiting dis9. See infra notes 47-60 and accompanying text. 10. See infra notes 21-29 and accompanying text. 11. See infra notes 32-60 and accompanying text. 12. See infra notes 61-117, 133-47 and accompanying text. 13. See infra notes 94-117, 138-47 and accompanying text. 14. See infra notes 118-28, 148-50 and accompanying text. 15. See infra notes 151-97 and accompanying text. 16. See infra notes 32-34, 52-54 and accompanying text. 17. See infra notes 172-97 and accompanying text. 18. U.S. CoNST. amend. VIII. See Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660, 664-66, 676 (1962) (applying the eighth amendment to the states and holding that any criminal sentence imposed for narcotics addiction would be cruel and unusual punishment). 19. See infra notes 20-29 and accompanying text. 19921 PROPORTIONALITY 1251 proportionate punishment. 20 Commentators who have adopted the traditional view ("traditionalists") argue that the framers of the Constitution borrowed the text and meaning of the eighth amendment from the English Declaration of Rights of 1689.21 The traditionalists have asserted that the English prohibited cruel and unusual punishments in reaction to the horrendous treason trials of 1685, during which Chief Justice Jeffreys imposed inhumane punishments on prisoners.2 2 The traditionalists argue that the American framers adopted the language and meaning of the English clause and, therefore, meant to prohibit only forms of inhumane punishments such as 23 those used in the treason trials. Nontraditionalist commentators urge that the cruel and unusual punishment clause of the English Declaration of Rights prohibited barbarous acts, but also included the principle proscribing punishments disproportionate to the crime.24 One commentator has theorized that the English clause was not a reaction to the 1685 treason trials, but to the perjury trial of Titus Oates, who was sentenced in 1685 to a series of humiliating punishments for fabricating a plot to kill Charles II.2 This commentator alleged that the House of Commons and a minority of the House of Lords condemned the sentences imposed on Oates as "cruel and unusual," not because of the form of the punishment, but because the punishment was excessive in relation to the crime of perjury. 26 This commentator further argued that the English cruel and unusual punishment clause prohibited punishments not authorized by statute, prohibited punishments beyond the jurisdiction of the sentencing court, and codified the English common-law prohibition 20. Schwartz, Eighth Amendment ProportionalityAnalysis and the Compelling Case of William Rummel, 71 J. CRiM. L. & CRIMINOLOGY 378, 382 (1980); Note, The Cruel and Unusual Punishment Clause and the Substantive CriminalLaw, 79 HARv. L. REV. 635, 636 (1966). 21. Schwartz, 71 J. CRIM. L. & CRIMINOLOGY at 378. Note, 79 HARv. L. REV. at 636. The English clause states: "excessive bail ought not to be required nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted." 1 W. & M., sess. 2, c. 2. 22. Schwartz, 71 CRiM. L. & CRIMINOLOGY at 378 (describing the traditional English method of execution, which consisted of first hanging, then disemboweling, and finally beheading and quartering). 23. Note, 79 HARv. L. REV. at 636-37. 24. Granucci, "Nor Cruel and Unusual Punishments lflicted": The Original Meaning, 57 CALIF. L. REV. 839, 860 (1969); SOURCES OF OUR LIBERTIES (R. Perry rev. ed. 1978). 25. Granucci, 57 CALIF. L. REV. at 855, 858. 26. Id. at 858-59. Granucci stated that none of the punishments imposed on Oates were prohibited by the government nor were they considered tortuous. Therefore, the reference to Oates's sentences being "cruel and unusual" must refer to the excessiveness or disproportionality of the sentence. Id. 1252 CREIGHTON LAW REVIEW [Vol. 25 against disproportionate sentences.27 The commentator further found that the American framers misinterpreted the English clause to prohibit only barbarous modes of punishment. 2s The commentator concluded that this misinterpretation "spawned the American doctrine that the words 'cruel and unusual' proscribed not excessive but tortuous punishments. " 29 Unfortunately, the records of the American state ratifying conventions and of the First Congress do not illuminate the current substantive content of the cruel and unusual punishment clause.30 The historical evidence indicates a concern with proscribing the use of torture by the new government, but there is no explicit evidence of 3l debate over the proportionality principle. THE UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT'S ANALYSIS OF A HISTORICAL JUSTIFICATION FOR THE PROPORTIONALITY PRINCIPLE In Harmelin v. Michigan,3 2 Justice Scalia's concurrence detailed the historical and textual origins of the eighth amendment and, on that basis, concluded that the eighth amendment does not encompass 27. Id. at 860. See SOURCES OF OUR LIBERTIES, supra note 24, at 236 (supporting the proposition that the cruel and unusual punishment clause incorporated the principle of English law that the length and severity of a punishment must fit the crime); Comment, The Eighth Amendmen Beccaria, and the Enlightenment: An Historical Justificationfor the Weems v. U.S. Excessive Punishment Doctrine, 24 BUFFALO L. REV. 783, 816-18 (1975) (arguing that Beccaria, an eighteenth century philosopher who subscribed to proportionality in sentencing, influenced colonial Americans and therefore, historical justification exists for the proposition that the eighth amendment encompasses the proportionality principle). But see Schwartz, 71 J. CRIM. L. & CRIMINOLOGY at 380-81 (criticizing Granucci's historical justification for finding a proportionality principle). Granucci argued that the prohibition of excessiveness in punishment was first expressed in the Bible in the concept of lex talionis - an eye for an eye. Granucci then noted a concern with proportionality by Greek philosophers, and later in eighth century English law. By 1066, the concept of proportionality gave way to discretionary amercements. Three chapters of the Magna Carta subsequently were devoted to regulation of excessive amercements. Granucci asserts that prior to adoption of the English Bill of Rights in 1689, English. law contained a prohibition against excessive punishments. Granucci noted that the provision was later adopted in the Virginia Declaration of Rights of 1776, and that the framers used virtually identical language in the eighth amendment. Granucci, 57 CALIF. L. REV. 844-45, 847, 853. 28. Granucci, 57 CALIF. L. REV. at 865. 29. Id. 30. See Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238, 258-63 (1972) (Brennan, J., concurring) (asserting that the brief statements from the conventions and the scanty debate from the First Congress, which referred to the cruel and unusual punishment clause, only revealed that the Framers were concerned with the misuse of legislative power, but did not reveal what punishments they considered to be "cruel and unusual"). 31. Id. at 259 (quoting Patrick Henry's speech at the Virginia ratifying convention in which Henry argued for a cruel and unusual punishment clause in the Federal Bill of Rights because, concerning punishments "no latitude ought to be left, nor dependence put on the virtue of representatives"). 32. 111 S.Ct. 2680 (1991). 1992] PROPORTIONALITY 1253 a proportionality principle, but only outlaws modes of punishment that are cruel and unusual.33 Justice Scalia noted that the words "cruel and unusual" must be read in the conjunctive, and therefore although a punishment may be cruel, it must also be uncommon to the American law to be a violation of the eighth amendment.34 Justice Brennan, concurring in the judgment of the per curiam, reached a contrary conclusion in Furman v. Georgia,35 a capital sentencing decision that held that imposition of the death penalty could violate the eighth amendment when imposed for certain crimes. 36 Justice Brennan determined that the framers had intended to ban tortuous punishment, but found that historical evidence did not support the additional conclusion that this was the framers' only intent.3 7 Instead, Justice Brennan argued that the language of the clause was indefinite and should be adapted to changing conditions and purposes brought about by time.38 In his concurring opinion in Furman,Justice Thurgood Marshall further argued that because the cruel and unusual punishment clause follows language that prohibits excessive fines and excessive bail, "[t]he entire thrust of the eighth amendment is, in short, against that which is excessive." 39 Justice Marshall concluded that the cruel and unusual punishment clause does proscribe punishments found to be excessive in relation to the offense. 40 THE PROPORTIONALITY PRINCIPLE: BEYOND HISTORICAL JUSTIFICATION TO AN EVOLVING STANDARD The United States Supreme Court announced that a punishment must be proportionate to the offense in Weems v. United States.4 1 In Weems, a Philippine government official was convicted of falsifying public documents and was sentenced to fifteen years of cadena temporal, a punishment involving chaining the wrists and ankles, forcing the prisoner to do hard and painful labor, and imposing additional accessory penalties on the prisoner during and after his imprison33. Id. at 2686-96. 34. Id. at 2687. 35. 408 U.S. 238 (1972). 36. Id. at 239-40; Id. at 263-64 (Brennan, J., concurring). Justices Douglas, Brennan, Stewart, White and Marshall made up the per curiam and each filed a concurring opinion supporting the judgments. Chief Justice Burger, Justices Blackmun, Powell, and Rehnquist each filed separate dissenting opinions. Id. at 240. 37. Id. at 263 (Brennan, J., concurring). 38. Id. at 263-64. 39. Id. at 332 (Marshall, J., concurring). 40. Id. at 331-32. 41. 217 U.S. 349 (1910). 1254 ment.42 CREIGHTON LAW REVIEW The Court reversed Weems' [Vol. 25 conviction, finding his punishment to be disproportionate to his crime, and therefore violative of the cruel and unusual punishment clause of the eighth amendment.43 The Court held that it is a precept of justice and of the fundamental law that a sentence be proportionate to the offense both in degree and in kind. 44 In condemning Weems' sentence as cruel and unusual, the Court compared Weems' sentence with sentences imposed for more serious offenses in the same jurisdiction. 45 The Court found, for example, that some homicides were not punished as severely as the less grave crime of falsifying documents.4 Some members of the Court have given the Weems decision precedential weight to support the proposition that challenges to sentences based on their disproportionate length could be reviewed for constitutionality. 47 Members of the Court who have rejected such a broad proportionality guarantee in noncapital sentences have limited the Weems holding to its facts.48 These members have argued that in Weems, because the Court considered the extraordinary nature of the accessories included in cadena temporal, the length of imprisonment alone was not the basis of the Weems decision. 49 Although Weems' precedential weight may be limited, the decision offered an alternative to purely textual and historical analysis of the eighth amendment.5° The Court stated: [T]ime works changes, brings into existence new conditions and purposes. Therefore a principle to be vital must be capa42. Id. at 357-58, 363. The additional accessories imposed on Weems included denial of his parental rights and his right to participate in family or property during his punishment. Also, following his term, Weems would be subjected to various methods of surveillance by the government. Id. at 363-64. 43. Id. at 382. Although the eighth amendment was not applicable to the states at this time, the Court stated that the Philippine Bill of Rights must be interpreted as the Court would interpret the Federal Bill of Rights, because the wording and spirit of the Phillipine Bill of Rights were identical to that found in the federal constitution. Id. at 367. 44. Id. at 366-67, 377. 45. Id. at 380-81. 46. Id. at 380. 47. Solem v. Helm, 463 U.S. 277, 286-87 (1983). Justice Powell, joined by Justices Brennan, Marshall, Blackmun, and Stevens, deemed Weema the "leading case" supporting the proposition that the eighth amendment guarantees proportionality review of noncapital sentencing. Id. 48. Rummel v. Estelle, 445 U.S. 263, 272-74 (1980). Justice Rehnquist was joined by Chief Justice Burger and Justices Stewart, White, and Blackmun. Id. 49. Id. at 274. 50. Weems, 217 U.S. at 373. The Weems Court stated that the eighth amendment should not be interpreted as referring to the physical abuses and penalties inflicted during the reign of Stuarts, otherwise the cruel and unusual punishment clause would have no meaning today. Instead, the Weems Court argued that the framers were concerned with legislative abuse of power. Id. at 372-73. 1992] PROPORTIONALITY 1255 ble of wider application than the mischief which gave it birth. This is peculiarly true of constitutions... In the application of a constitution, therefore, our contemplation cannot 5 be only of what has been but of what may be. ' This conception of the Constitution as a vital and living document, subject to changing interpretation, has been termed the "evolving 52 standard." A plurality of the Supreme Court in Trop v. Dullesss held that the punishment of denationalization of an American citizen for wartime desertion was cruel and unusual punishment within the meaning of the eighth amendment. 54 Chief Justice Warren, writing for the plurality, announced that the "[eighth] [a]mendment must draw its meaning from the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society." 5 Chief Justice Warren suggested that the "evolving standard" be measured by determining whether the sentence offends the "cardinal principles for which the constitution stands," and by comparing the sentence with those imposed for similar crimes in other nations.5s After Trop, the Supreme Court continued to rely on an "evolving standard" in its capital sentencing decisions as a basis for proportionality analysis. 57 For example, in Coker v. Georgia,m the Court held that the death penalty was disproportionate to the crime of rape. 59 In Coker, the Court found a punishment excessive if the punishment 51. Id. at 373. 52. Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86, 101 (1958) (plurality opinion); see Judge Mulligan, Cruel and Unusual Punishments" The ProportionalityRule, 47 FoRD. L. REV. 649 (1979) (arguing that Weems concerned barbarous punishment and did not represent affirmative precedent for a proportionality principle, but because the clause is evolutionary in character and barbarous punishments have disappeared, the clause must be applied to extraordinarily excessive terms). Chief Justice Warren cites Weems for the proposition that the scope of the eighth amendment is not static and its language is imprecise. Trop, 356 U.S. at 100-01. 53. 356 U.S. 86 (1958) (plurality opinion). 54. Id. at 101. 55. Id. 56. Id. at 102. 57. See, e.g., Enmund v. Florida, 458 U.S. 782, 788, 801 (1982) (holding that the death penalty is cruel and unusual punishment for accomplice felony murder); Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153, 179-183, 207 (1976) (holding that the evolutionary standard mandates the death penalty as applied to murder in the case at bar); Furman,408 U.S. at 269-70. Justice Brennan argued that if a strictly "'historical"' interpretation of the cruel and unusual punishments clause prevailed, the clause would have been effectively read out of the Bill of Rights." Instead, Justice Brennan stated that the cruel and unusual punishment clause must be interpreted so that it comports with human dignity. He suggested that one way to do this analysis is to look to the present practices of society, i.e., legislative decisions, to determine if a particular punishment is still considered dignified. Id. at 265, 270. 58. 433 U.S. 584 (1977). 59. Id. at 592. 1256 CREIGHTON LAW REVIEW [Vol. 25 "(1) makes no measurable contribution to acceptable goals of punishment and hence is nothing more than the purposeless and needless imposition of pain and suffering; or (2) is grossly out of proportion to the severity of the crime." 6 The Court evaluated both prongs by examining objective factors to the maximum extent possible, including history and precedent, and public and legislative attitudes toward the 61 crime and sentence. THE CURRENT STATE OF THE PROPORTIONALITY PRINCIPLE RUMMEL V. ESTELLE: THE FIRST OF THE PROPORTIONALITY TRILOGY Outside the context of capital sentencing, the Supreme Court did not accept another proportionality challenge until 1983, when it decided Rummel v. Estelle.6 2 Justice Rehnquist, writing for the plurality in Rummel, emphasized the twin themes that would be central to later proportionality decisions: judicial deference to the legislature 63 and avoidance of subjective decisionmaking. Rummel received a mandatory life sentence with the possibility of parole under a recidivist statute for obtaining $120.75 by false pretenses.64 Rummel was previously convicted of two relatively minor felonies: using a credit card fraudulently to obtain goods or services worth $80.00, and passing a forged check for $28.36.65 The Court denied Rummel's proportionality challenge, finding that his sentence was not cruel and unusual punishment within the meaning of the eighth amendment. 66 In Rummel, Justice Rehnquist wrote, "one could argue without fear of contradiction by any decision of this Court that for crimes concededly classified and classifiable as felonies, that is, as punishable by significant terms of imprisonment in a state penitentiary, the 60. Id. (citing Gregg, 428 U.S. at 183, 187). 61. Id. 62. 445 U.S. 263 (1980) (plurality opinion). 63. Id. at 274. Justice Rehnquist was joined by Chief Justice Burger, Justices Blackmun, Stewart, and White. Id. at 264. 64. Id. at 266-67. Rummel was sentenced under Article 63 of the Penal Code of the State of Texas "which provided that '[w]hoever shall have been three times convicted of a felony less than capital shall on such third conviction be imprisoned for life in the penitentiary."' Id. at 264 (recodified as TEX. PENAL CODE ANN. § 12.42(d) (Vernon 1974). 65. Id. at 265-66. 66. Id. at 265. Rummel's challenge was based on a four-factor proportionality analysis gleaned from Hart v. Coiner, 483 F.2d 136, 140-43 (4th Cir. 1973), cert. denied, 415 U.S. 983 (1974). Id. at 267. In Hart, the Fourth Circuit held that a mandatory life sentence for four non-violent felonies imposed under the West Virginia recidivist statute was unconstitutionally disproportionate. Hart, 483 F.2d at 143. 1992] PROPORTIONALITY 1257 length of the sentence actually imposed is purely a matter of legislative prerogative." 67 Justice Rehnquist stated that "It]his is not to say that a proportionality principle would not come into play in the extreme example mentioned by the dissent, if a legislature made overtime parking a felony punishable by life imprisonment."8 Therefore, the plurality acknowledged that proportionality review may be necessary in rare noncapital sentencing decisions. 69 However, Justice Rehnquist did not advance any criteria for making a proportionality determination if these hypothetical situations were realized. 70 The dissent objected to the plurality's narrow characterization of the proportionality principle. 7 ' Justice Powell, writing for the dissent, argued that based on history and precedent, the Court had a constitutional obligation to undertake proportionality review of challenged capital and noncapital sentences.72 Justice Powell outlined a three-prong test to measure the proportionality of a sentence and to "minimize the risk of constitutionalizing the personal predilections of 73 The dissent stated that the following factors were federal judges."1 together and that no single factor should control: be considered to "(i) the nature of the offense; (ii) the sentence imposed for commission of the same crime in other jurisdictions; and (iii) the sentence imposed upon other criminals in the same jurisdiction." 74 After applying the three factors, the dissent concluded that for Rummel's 67. Rummel, 445 U.S. at 265. The Court criticized the challenging defendant for relying on capital sentencing decisions to support proportionality review of his sentence. The Court found that because death is irrevocable and uniquely different in kind to all other forms of punishment, the mode of analysis used in capital cases is"of limited assistance in deciding the constitutionality" of a sentence of life imprisonment. Id. at 272. 68. Id. at 274 n.11. (citations omitted). 69. Id. The dissent in Rummel relied on this footnote to argue that a proportionality principle remained applicable in noncapital sentencing decisions. Id. at 306, 307 n.25 (Powell, J., dissenting). 70. Id. at 274. 71. Id. at 288, 295 (Powell, J., dissenting). Justice Powell was joined by Justices Brennan, Marshall, and Stevens. Id. at 285. 72. Id. 73. Id. at 295. As to the scope of this inquiry, Powell noted that a court must focus on whether an offender deserves such punishment, not solely on utilitarian goals. To illustrate, Powell stated that a mandatory life sentence levied against overtime parkers may deter this practice, but it would offend our sense of justice. Id. at 288. See generally James, Eighth Amendment ProportionalityAnalysis: The Limits of Moral Inquiry, 26 ARIz. L. REv. (1984) (arguing that proportionality analysis is inherently a moral judgment because the concept of proportionality is based on the retributive theory of punishment). 74. Rummel, 445 U.S. at 295 (Powell, J., dissenting) (citations omitted). Justice Powell argued that drawing the line between forging a check for $28 and violent crime was no more difficult than making that determination between murder and rape. Id. (citing Coker, 433 at 598). Justice Powell warned the Court not to allow difficulties of 1258 CREIGHTON LAW REVIEW [Vol. 25 crimes of defrauding others of a total of $230, Texas had imposed a disproportionate sentence on Rummel by depriving him of "his free'75 dom for life." Justice Rehnquist's plurality opinion criticized the proportionality analysis offered by the dissent. 76 Justice Rehnquist argued that a factor considered by the dissent, the absence of violence in Rummel's offenses, was inconclusive evidence of the lesser gravity of his offenses because the interest of society in deterring nonviolent crimes may be greater in some circumstances than in deterring certain violent crimes. 77 Justice Rehnquist found that to compare Rummel's life sentence imposed under the Texas recidivist statute to the recidivist sentencing schemes of other states would be too complex given distinctions between states, such as varied positions concerning the 78 possibility of parole and different levels of prosecutorial discretion. Justice Rehnquist further argued that a comparison of punishments imposed for other offenses within Texas would reveal only inherently speculative conclusions of proportionality because each offense would implicate different societal interests, and thus would be de79 serving of different sentencing lengths. Hum-l v. DAVIS: THE SECOND CASE IN THE TRILOGY In Hutto v. Davis,80 the Court held that a forty-year prison term, imposed for possession of nine ounces of marijuana with intent to distribute, was not an unconstitutionally disproportionate sentence. 8 l The Court stated that the Fourth Circuit, by affirming the disproportionality finding of the lower court, had disregarded the Rummel decision, which held that courts should reluctantly review noncapital sentences and should rarely find a noncapital sentence disproportionate.8 2 The Court found that the United States Court of Appeals for linedrawing in other cases to obscure its vision on the extreme facts in Rummel. Id. at 295-96 n.12. 75. Id. at 295, 299, 299 n.19. 76. See infra notes 77-79 and accompanying text. 77. Rummel, 445 U.S. at 282 n.27. 78. Id. at 280-81. 79. Id. at 282 n.27. For example, embezzlement or dealing in hard drugs are not violent but assault a unique set of social values. Id. 80. 454 U.S. 370 (1982). 81. Id. at 371, 375. Davis, a Virginia prisoner, on a writ of habeas corpus, challenged his sentence as disproportionate and used the analysis from Hart v. Coiner, 483 F.2d 136 (4th Cir. 1973), cert. denied, 415 U.S. 983 (1974). Davis, 454 U.S. at 371. 82. Davis, 454 U.S. at 372, 374. The trial court had found Davis' sentence to be so grossly disproportionate to the crime as to constitute cruel and unusual punishment. Davis v. Zahradnick, 432 F. Supp. 444, 453 (W.D. Va. 1977). The lower court examined the nature of the offense, the punishments in Virginia for other crimes, and the legislative purpose behind the punishment. Id. The United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, on rehearing en banc, PROPORTIONALITY 1992] 1259 the Fourth Circuit had "sanctioned an intrusion into the basic linedrawing process that is 'properly within the province of the legislatures, not courts.' "83 The dissent in Davis, authored by Justice Brennan and joined by Justices Marshall and Stevens, stated, "the per curiam,by suggesting that it was improper for the courts below to engage in a disproportionality analysis, represents a serious and improper expansion of Rummel."" The dissent asserted that proportionality review was an eighth amendment guarantee to be applied to Davis' noncapital sentence and concluded that under such a review, the sentence was unconstitutional.8s SOLEM V. HELM: THE FINAL CASE OF THE PROPORTIONALITY TRILOGY In Solem v. Helm,s8 Justice Powell, writing for the majority, resurrected a slightly modified version of the three-factor proportionality analysis ("Solem three-prong test") that he first outlined in his dissent in Rummel.8 7 Justice Powell's factors were "(i) the gravity of the offense and the harshness of the penalty; (ii) the sentences imposed on other criminals in the same jurisdiction; and (iii) the sentences imposed for commission of the same crime in other jurisdictions." s The majority concluded from its analysis that a life sentence without parole, imposed on Helm under the South Dakota recidivist statute for passing a no-account check, was a violation of the eighth amendment because the sentence was not proportionate to found the analysis and the conclusion of the district court correct. Davis v. Davis, 601 F.2d 153, 154 (4th Cir. 1979). After granting certiorari, the United States Supreme Court remanded the case to the Fourth Circuit with instructions to reconsider its original holding in light of the Rummel decision. Hutto v. Davis, 445 U.S. 947 (1980). The Fourth Circuit affirmed the district court a second time. Davis v. Davis, 646 F.2d 123, 124 (4th Cir. 1981). 83. Davis, 454 U.S. at 374 (quoting Rummel, 445 U.S. at 275-76). Justice Powell concurred in the judgment of the Court although he argued that the sentence was disproportionate. Justice Powell found that Rummel was controlling because Rummel's petty crimes were far less severe than Davis' drug dealings and yet Rummel's sentence was more harsh than that of Davis. Justice Powell further argued that Davis had failed to demonstrate by statutory comparison the greater disproportionality of his sentence. Id. at 375, 377, 379-80 (Powell, J., concurring). 84. Id. at 382-83 (Brennan, J., dissenting). The dissent argued that the Court based its holding on the overwhelming state interest in deterring habitual offenders and did not come to the issue of the proportionality of the harsh sentence. Id. at 382. 85. Id. at 383-84, 386. 86. 463 U.S. 277 (1983). 87. Id. at 292. See supra notes 73-74 and accompanying text. Justice Blackmun, who had voted with the plurality in Rummel, joined the Court in Solem, enabling them to maintain a majority. Solem, 463 U.S. at 279. See supra note 75 and accompanying text. 88. Solem, 463 U.S. at 292. 1260 CREIGHTON LAW REVIEW [Vol. 25 the crime.8 9 In Solem, Justice Powell's majority maintained that the eighth amendment prohibited disproportionate sentences in both capital and noncapital sentencing. 9° Justice Powell declared that "no penalty is per se constitutional." 9 1 The majority argued that Rummel should control only similar factual situations because, although the Rummel Court had recognized that some sentences may be so grossly disproportionate as to violate the eighth amendment, the Court had failed to offer a mode of analysis to conduct proportionality review. 92 Justice Powell distinguished Solem from Rummel based on the fact that Rummel's life sentence offered the possibility of parole, whereas Solem would serve 93 a more severe sentence of life imprisonment without parole. The Solem dissent, written by Justice Burger, found that the plurality was disingenuous in its characterizations of history and proportionality precedent. 94 The dissent argued that history and precedent demanded adherence to a more narrow proportionality principle to be applied in capital cases and in those rare noncapital "cases where reasonable men cannot differ as to the inappropriateness of a punishment. '95 The dissent also rejected the Solem three-prong test because the test required a reviewing court to measure sentences based on an unacceptably "abstract moral scale." 96 HARMELIN V. MICHIGAN. THE CURRENT STATE OF PROPORTIONALITY The proportionality principle was reexamined by the Supreme Court in Harmelin v. Michigan.97 In Harmelin, the Court held that a mandatory life sentence without the possibility of parole for possession of 672 grams of cocaine was not so grossly disproportionate as to 89. Id. at 284. Helm, after serving two years of his life sentence, challenged his sentence on the basis of disproportionality. His prior felony convictions were three third-degree burglaries, the offense of obtaining money under false pretenses, grand larceny, and a third offense of driving while intoxicated. First, the Court found Helm's crimes to be of lesser gravity than other crimes because Helm's crimes were all nonviolent and victimless. Second, his sentence was found to be the most severe available in South Dakota. Helm was found to have been treated in the same manner or more severely than criminals having committing far more serious crimes in South Dakota. Third, the court found Helm had been treated more severely than he would have been in any other state. Id. at 279-80, 283, 296-300. 90. Id. at 289-90. 91. Id. at 290. 92. Id. at 303-04 n.32. 93. Id. at 304 n.32. 94. Id. at 304, 313 (Burger, J., dissenting). 95. Id. at 311 n.3. 96. Id. at 306. 97. 111 S.Ct. 2680 (1991). 1992] PROPORTIONALITY 1261 violate the cruel and unusual punishment clause of the eighth amendment. 98 Justice Scalia, authoring one concurrence, found that the eighth amendment did not contain a proportionality principle." Justice Scalia argued that although the language of the eighth amendment could bear a construction that would sustain a finding of a proportionality principle, this interpretation was outweighed by the historical evidence against it. 1 ° Justice Scalia argued that if the framers had wanted to include a proportionality principle in the eighth amendment, they would have modeled the language of the eighth amendment after existing state constitutions that stated the proportionality principle explicitly. 1 1 Justice Scalia concluded that the decision in Solem should be overruled and rejected the Solem three-prong test advocated by the Harmelin dissent.10 2 According to Justice Scalia, the first prong, analyzing the gravity of the offense and the harshness of the penalty, was of no utility because there was no objective standard by which to compare the gravity of different offenses. 10 3 Justice Scalia's concurrence argued that the second prong, comparing sentences imposed for other offenses in the same jurisdiction, could not be analyzed because judges could not compare sentences of similarly grave crimes without an objective standard of gravity. 1 4 Justice Scalia's concurrence further found that the third prong, comparing sentences imposed for the same crime in other jurisdictions, was irrelevant to an eighth amendment analysis because such an analysis suggested that one state must criminalize acts in a fashion similar to another state.'0 5 Justice Scalia's concurrence argued that such a demand for state conformity would be inimical to the principles of federalism. 1° 6 Justice Scalia concluded that state legislatures should make proportionality evaluations on the appropriate length of sentences because such judgments 98. Id. at 2701-02, 2709. Harmelin, who had no prior criminal record, was sentenced under a Michigan statute that provided a mandatory life sentence without parole for possession of 650 grams or more of any mixture containing a controlled substance. Harmelin challenged his sentence based on its significant disproportionality, and based on the fact that the sentencing judge was unable to consider any mitigating factors. Id. at 2684, 2684 n.1. 99. Id. at 2686 (Scalia, J., concurring). 100. Id. at 2692. 101. Id. at 2692, 2692 n.8 (quoting the New Hampshire Bill of Rights as an example of a state constitutional provision existing prior to the time the eighth amendment was adopted that detailed a proportionality guarantee separate from its cruel and unusual punishment clause). 102. Id. at 2686, 2697-99. See supra notes 87-91 and accompanying text. 103. Harmelin, 111 S.Ct. at 2698. 104. Id. 105. Id. at 2698-99. 106. Id. at 2699. 1262 CREIGHTON LAW REVIEW [Vol. 25 involve subjective decisionmaking, something beyond the realm of ju07 dicial power.' Justice Scalia's concurrence dismissed the need to preserve a proportionality principle to guard against the possibility of a legislature making overtime parking punishable by life imprisonment. 0 8 Justice Scalia wrote, "one can imagine extreme examples that no raexamtional person... could accept. But for the same reason ithese 9 ples are easy to decide, they are certain never to occur."' In Harmelin, seven members of the Supreme Court found that the eighth amendment did contain a proportionality principle."i 0 However, these members of the Court divided over the most accurate mode of proportionality review."' Justice Kennedy agreed with Justice Scalia's concurring judgment, but argued in a second concurrence that stare decisis required the Court to adhere to a narrow proportionality principle."i 2 Justice Kennedy argued that proportionality analysis should be governed by four points of commonality from past decisions: (1) substantial deference should be given to legislative criminal sentencing judgments; (2) the eighth amendment does not require the states to adhere to any one penalogical theory; (3) the differences among state sentencing schemes are an inevitable and sometimes positive aspect of federalism, and therefore differences between states alone could never render a sentence disproportionate; and (4) a proportionality review must be informed to the greatest possible extent by objective factors."i 3 Justice Kennedy stated that these principles should inform the final principle that "the Eighth Amendment does not require strict proportionality between crime and sentence," but prohibits only those sentences grossly disproportionate relative to 14 the crime. Justice Kennedy applied the Solem three-prong test and argued that if the analysis of prong one, the gravity of the crime compared to the harshness of the sentence, did not reveal gross disproportionality between the sentence and the crime, then the court should end its re107. Id. at 2698-99. 108. Id. at 2696-97, 2697 n.11. But see Brennan, Reason, Passion,and "The Progress of the Law", 10 CARDozo L. REV. 21-22 (1988). 109. Harmelin, 111 S.Ct. at 2696-97. 110. See supra note 8 and accompanying text. See infra notes 112, 117-20 and accompanying text. 111. See infra notes 112-20 and accompanying text. 112. Harmelin, 111 S. Ct. at 2702. 113. Id. at 2703-05. Justice Kennedy further argued that the "relative lack of objective standards concerning terms of imprisonment has meant that '[o]utside the context of capital punishment, successful challenges to the proportionality of particular sentences [are] exceedingly rare.'" Id. at 2705. (quoting Solem, 463 U.S. at 289-90 (quoting Rummel, 445 U.S. at 272)). 114. Id. at 2705. 19921 PROPORTIONALITY 1263 view. 1 15 He stated that if the threshold question indicated gross disproportionality, then a reviewing court should undertake a comparison of sentences imposed for other offenses in the same jurisdiction, or sentences imposed for the same offense in other jurisdic6 tions, only to validate its initial finding of disproportionality." The dissent in Harmelin, authored by Justice White rejected Justice Kennedy's modification and found that analysis under the original Solem three-prong test revealed that the mandatory sentence of life without parole imposed on Harmelin would be unconstitutionally disproportionate." 7 The dissent asserted that historical analysis of the cruel and unusual punishment clause was of limited helpfulness in determining the scope of the proportionality principle." 8 Rather, the dissent argued that a reviewing court must find that a sentence violates the eighth amendment, "if it is contrary to the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society.""19 The dissent found that objective factors, such as those outlined in the three-prong test, aided in identifying the "evolving 115. Id. at 2707. 116. Id. Justice Kennedy's review of Harmelin's sentence ended with the threshold inquiry because he found that the severity of Harmelin's crime "brings his sentence within the constitutional boundaries established by our prior decisions." Id. at 2706. 117. Id. at 2719 (White, J., dissenting). Justice White was joined by Justices Blackmun and Stevens. Id. Justice Powell, who outlined the Solem three-prong test to measure proportionality, retired from the Supreme Court in 1987. Nowak et al., Constitutional Law, Appendix A (3d ed. Supp. 1988). In Harmelin, Justice Marshall authored a separate dissent in which he agreed with the reasoning of Justice White's dissent, but also reiterated his view that the eighth amendment proscribes the death penalty. Id. at 2719 (Marshall, J., dissenting). Justice Stevens, joined by Justice Blackmun, in a separate dissent, added that mandatory life sentences without parole are similar enough to the death penalty in that the offender is permanently deprived of his freedom. Therefore, Justice Stevens argued, Harmelin's sentence can be justified only by a determination that the offense is so horrendous that "society's interest in deterrence and retribution wholly outweighs any considerations of reform or rehabilitation of the perpetrator." Id. at 271920 (Stevens, J., dissenting). 118. Id. at 2712 (White, J., dissenting). The dissent stated that when examining prong one, a reviewing court should look at "the harm caused or threatened to the victim or society." Id. at 2716 (quoting Solem, 463 U.S. at 294). The dissent contended that reviewing courts must consider that the "punishment must be tailored to a defendant's personal responsibility and moral guilt" in order to be constitutionally proportionate. Id. (citing Enmund v. Florida, 458 U.S. 782, 801 (1982)). The dissent found that life imprisonment without parole was the harshest penalty available in Michigan, and that the Michigan legislature imposed this penalty only on first-degree murderers, drug manufacturers, distributors, and possessors of 650 grams or more of a controlled substance. Id. at 2718. The dissent examined the sentences other states imposed for Harmelin's offense and concluded that because no other state provided such a severe penalty, "the degree of national consensus this Court has previously thought sufficient to label a particular punishment cruel and unusual" had been established. Id. at 2719 (quoting Stanford v. Kentucky, 492 U.S. 361, 371 (1989)). 119. Id. (quoting Trop, 356 U.S. at 101). 1264 CREIGHTON LAW REVIEW [Vol. 25 standards of decency" as reflected by objective societal indicators.120 LOWER COURTS' APPLICATION OF HARMELIN V. MicHIGAN Since the Court handed down its splintered decision in Harmelin, lower courts have applied the proportionality principle with varying results. 12 1 The United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, in United States v. Lemons,122 held that a thirty-year prison term for nine counts of bank fraud was not so disproportionate a sentence as to violate the eighth amendment. 123 The Fifth Circuit, in Lemon, because of the varied analyses employed by the divided Harmelin plurality, was able to continue to rely on the holding in Solem v. Helm, as evidenced by its use of the three-prong test.12 4 The court cited Harmelin only to offer reference to an example of the ap1 25 plication of the proportionality test. In contrast, the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, in United States v. Hopper,12 6 found Justice Kennedy's concurring opinion in Harmelin dispositive as the proper analysis of the proportionality decision before it. 1m The court reasoned that it must recognize a narrow proportionality principle because, "although only two Justices would have held that the eighth amendment has no proportionality requirement, five Justices agree that there is no require128 ment of strict proportionality.' The United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit rejected a proportionality challenge in United States v. Manuel,' 9 holding that a fifteen-month sentence for failure to appear for sentencing on a charge of federal forgery was not cruel and unusual pun120. Id. The dissent rejected Justice Kennedy's reading of Solem, which stated that "no single criterion can identify when a sentence is so grossly disproportionate that it violates the Eighth Amendment." Id. at 2714 (quoting Solem v. Helm, 463 U.S. 277, 291 n.17 (1983)). The dissent instead argued that all three factors must be evaluated in order for the analysis to be accurate. Id. See supra note 88 and accompanying text. 121. See irnfra notes 123-31 and accompanying text. 122. 941 F.2d 309 (5th Cir. 1991). 123. Id. at 319-20. 124. Id. A lower court does not need to follow a particular mode of analysis if a plurality of the United States Supreme Court agrees only in their judgment in a particular case and is split on the appropriate method for arriving at the judgment. Inter- view with Professor Michael Fenner, Professor at Law, Creighton University School of Law (February 26, 1992). 125. Lemons, 941 F.2d at 319. 126. 941 F.2d 419 (6th Cir. 1991). 127. Id. at 422. See United States v. Pickett, 941 F.2d 411 (6th Cir. 1991) (applying Harmelin to uphold a sentence imposed under a federal statute punishing conspiracy to deliver crack cocaine, and finding both concurring opinions in Harmelin to be viable analysis). 128. Hopper, 941 F.2d at 422. 129. 944 F.2d 414 (8th Cir. 1991). 1992] PROPORTIONALITY 1265 ishment.' 3 0 The court found that the Harmelin decision had modified Soalem, and "although the extent of ...[the] modification ... is not yet clear, it is evident that Solem's holding that the eighth amendment 'forbids only extreme sentences that are 'grossly dispro131 portionate' to the crime' is still controlling."' ANALYSIS THE STATE OF THE LAW AFTER HARMELIN The law of proportionality review is in an unsettled and unsatisfying state as a result of the divergent characterizations of the proportionality principle made by members of the Supreme Court.132 The problems arising out of the decisions in Rummel v. Estelle,'33 Hutto v. Davis,'34 and Soalem v. Helm'35 still remain because the decisions are viable to some extent following the decision in Harmelin v. 36 Michigan.' The rationale used by the Court in Rummel and Davis was problematic because, although the Court admitted the possibility that in rare instances a noncapital sentence could be unconstitutionally disproportionate to the crime committed, the Court in both decisions refused to provide any evaluating criteria and therefore, the Court allowed a constitutional deficiency to exist.'3 7 After Rummel and Davis, when a criminal defendant presented a reviewing court with a proportionality challenge to a noncapital sentence, the court had no 38 guidance with which to make such a determination. The Court in Soalem answered the absence of evaluating criteria by way of the three-prong test. 3 9 In Solem, the Court found that the proportionality principle assured the criminal defendant the constitutional right to a judicial determination that the noncapital or capital sentence imposed on him was proportionate to the crime he 140 committed. The Court in Solem failed to overrule Rummel and Davis and therefore, the Solem decision enabled the Supreme Court in Harme130. Id. at 415, 417. 131. Id. at 417 (quoting Harmelin, 111 S.Ct. at 2705) (Kennedy, J., concurring)). 132. See irqfra notes 141-50 and accompanying text. 133. 445 U.S. 263 (1980). 134. 454 U.S. 370 (1982). 135. 463 U.S. 277 (1983). 136. 111 S. Ct. 2680 (1991). See infra notes 141-50 and accompanying text. 137. Davis, 454 at 384 (Brennan, J., dissenting) (finding that the per curiam offered no analysis as to why the facts at issue did not fit into the Rummel rarity example). See supra notes 68-70, 76-79, 82-83 and accompanying text. 138. Soalem, 463 U.S. at 290 n.17. 139. See supra notes 88, 92-93 and accompanying text. 140. See supra notes 90-91 and accompanying text. 1266 CREIGHTON LAW REVIEW [Vol. 25 lin to recharacterize those opinions to support the divergent positions of the justices. 14 ' In Harmelin, Justice Scalia's concurrence characterized the Rummel and Davis decisions as restricting proportionality review solely to capital sentences.142 This characterization supported Justice Scalia's finding that the eighth amendment contains no proportionality principle. 143 Justice Scalia, to his credit, acknowledged that the Solem decision was incompatible with Rummel and Davis and should be overruled.'" In contrast, Justice Kennedy's concurrence in Harmelin attempted to reconcile the irreconcilable holdings of Rummel, Davis, and Solem by way of a modified Solem three-prong test.145 The modified test requires a first-prong analysis of the gravity of the offense and harshness of the sentence to reveal gross disproportionality in sentencing before the analyses of prongs two and three, the sentences imposed on other criminals in the same jurisdiction, and the sentences for commission of the same crime in other jurisdictions, are conducted. 14 Justice Kennedy argued that because Rummel and Davis rejected the use of a comparative analysis, his modification of 147 the Solem test reconciled the discordant precedent of Harmelin. Actually, Justice Kennedy manipulated the Solem holding to avoid overruling the decisions preceding Solem. 48 Despite Justice Kennedy's attempts, the mode of analysis used in Rummel and Davis cannot be reconciled with Solem because the Court in Solem looked at all three prongs-no factor controlled and all were necessary for accurate analysis. 49 In contrast, the Court, in Rummel, and in Davis, rejected any mode of analysis based on the factors making up the Solem three-prong test. 15° The lower courts are predictably split on the correct application of the proportionality principle because of the ambiguous resolution 5 in Harmelin.1 ' For example, the Fifth Circuit used a pure Solem 141. Harmelin, 111 S. Ct. at 2684-86 (Scalia, J., concurring) (arguing that the text and footnotes in Rummel and Davis were incorrectly expanded in Solem to permit the inference that challenges of gross disproportionality should be successful); Id. at 2703 (Kennedy, J., concurring) (stating that although different analyses were used in Rummel and Davis than in Solem, the Court in Solem announced that its decision was consistent with these two decisions and therefore, Justice Kennedy argued, the three decisions must be reconciled). 142. Id. (Scalia, J., concurring). 143. Id. 144. Id. at 2686. 145. See supra notes 8, 112-16 and accompanying text. 146. Harmelin, 111 S. Ct. at 2707 (Kennedy, J., concurring). 147. Id. 148. See supra notes 87-88, 117, 147 and accompanying text. 149. See supra notes 80-88, 117, 147 and accompanying text. 150. See supra notes 76-79 and 82-83 and accompanying text. 151. See supra notes 122-31 and accompanying text. PROPORTIONALITY 19921 1267 analysis to rule on a proportionality challenge to a thirty-year prison sentence.'5 2 The Sixth Circuit, when faced with a challenge to a tenmonth sentence, found that Justice Kennedy's concurrence in Harmelin required that a court only perform a cursory and generic examination of the crime committed, and that if the threat of the crime to society was found to be severe, then the proportionality test ended and the sentence would stand as constitutionally proportionate.153 The split of interpretations in the circuits will inevitably lead to a future reconsideration by the Supreme Court of the role of proportionality review. CRITICISM OF JUSTICE SCALIA'S ANALYSIS IN HARMELIN Why is the law in this difficult state, and what is the real obstruction to coherent resolution of the proportionality debate? The primary difficulty lies with each member of the Court attempting, based on their own exemplars of constitutional interpretation, to give meaning to the ambiguously worded eighth amendment.'" This Analysis will undertake an informal critique of the textual and historical mode of eighth amendment interpretation used by Justice Scalia in Harmelin.155 This Analysis will then look at a more sound and fair alternative, the "evolving standard" of eighth amendment interpretationlM6 JUSTICE SCALIA'S GENERAL PRINCIPLE: No PROPORTIONALITY PRINCIPLE After an exhaustive review of eighth amendment background, Justice Scalia found textual and historical evidence dispositive when he concluded, "the Eighth Amendment contains no proportionality guarantee."'1 57 A clear decision from a majority of the Court, prohibiting proportionality review of noncapital sentences, would surely have been more instructive than the discordant guidance before and 152. See supra notes 122-25 and accompanying text. 153. See supra notes 126-28 and accompanying text. 154. See generally Scalia, Originalism:The Lesser Evil, 57 U. CIN. L. REV. 849, 854 (1989) (arguing that the originalist approach to constitutional interpretation, based on text and evidence of contemporaneous understandings, is preferable to nonoriginalism, based on nonhistorical evidence such as evolving standards, and that the text of the Constitution does not give the judiciary the power to judge the constitutionality of federal laws). Debate over constitutional interpretive theory is beyond the scope of this Analysis. See generally INTERPRETING LAW AND LITERATURE (S. Levinson & S. Mail- loux ed. 155. 156. 157. 1988). See supra notes 99-101, 118-20, and accompanying text. See infra notes 158-75 and accompanying text. See infra notes 176-200 and accompanying text. Harmelin, 111 S. Ct. at 2686. See supra notes 33-34 and accompanying text. 1268 CREIGHTON LAW REVIEW [Vol. 25 after Harmelin.1 m However, Justice Scalia's general principle, denying the existence of a proportionality principle, is inconsistent with his mode of analysis and inferior to the proportionality principle for three reasons. 159 First, accepting the proposition that the eighth amendment contains no proportionality principle means that such a principle cannot be valid at all, even in the context of capital sentencing.1' ° Second, by denying judicial review of sentences challenged on the basis of disproportionate length, the legislatures retain an almost 161 unrestricted grant of power to make such sentencing decisions. And third, past proportionality decisions of the Court mandate the use of the fairer and sounder "evolving standard of decency" to ana162 lyze proportionality. PROPORTIONALITY AND CAPITAL SENTENCING Justice Scalia wrote in Harmelin, "[p]roportionality review is one of several respects in which we have held that 'death is different,' and have imposed protections that the Constitution nowhere else provides."'' 1 3 Based on a purely textual and historical interpretation of the eighth amendment, Justice Scalia's proposition that no proportionality principle exists except in death penalty cases is plainly inconsistent. 164 If the eighth amendment contains no proportionality principle, then the principle can be applied neither in capital sentencing cases nor in noncapital cases. 1 65 If a majority of the Court adopted Justice Scalia's mode of analysis and his conclusion, then the Court would effectively invalidate all prior decisions based on the proportionality principle wherein the death penalty was found to be disproportionate in relation to the crime committed. 166 Justice Scalia's assumption that death sentences are necessarily different in excessiveness from all other sentences, including the life 16 7 sentence without parole imposed on Harmelin, is also problematic. Justice Scalia's analysis renders life sentences without parole less horrible than death, and thus not worthy of the constitutional protection offered by proportionality review. 16 Although through judicial 158. See supra notes 90-96 and accompanying text. 159. See infra notes 163-81 and accompanying text. 160. See injfra notes 163-69 and accompanying text. 161. See infra notes 170-75 and accompanying text. 162. See infra notes 176-81 and accompanying text. 163. Harmelin, 111 S. Ct. at 2701. 164. See supra notes 20-23, 33-34 and accompanying text. See infra note 162 and accompanying text. 165. Harmelin, 111 S. Ct. at 2712 (White, J., dissenting). 166. See supra notes 35-40, 57-61, 163-65 and accompanying text. 167. Harmelin, 111 S. Ct. at 2719-20 (Stevens, J., dissenting). 168. Id. at 2683. 1992] PROPORTIONALITY 1269 decisionmaking the "death is different" principle has become a part of American jurisprudence, the history and the text of the eighth amendment reveal no distinction between a deprivation of life and the most serious deprivations of liberty.' 69 Therefore, both deserve equal eighth amendment protection. UNRESTRAINED LEGISLATIVE PREROGATIVE IN NONCAPITAL SENTENCING Accepting Justice Scalia's analysis in Harmelin, the judiciary would not have the power to review a noncapital sentencing decision challenged on the basis of its disproportionate length. 170 Justice Scalia's assertion-that a disproportionate unconstitutional use of sentencing power by a legislature would be so obvious that it would be certain never to occur-removes the proverbial "safety net" once provided by the Rummel overtime parking hypothetical.' 71 Justice Scalia's opinion renders the length of all noncapital sentencing decisions constitutional per se, regardless of the relative gravity of the 72 offense.' Penalogical decisions, specifically criminal sentencing determina173 tions, appropriately originate in the state and federal legislatures. The courts must respect and defer to legislative decision; the states must be allowed to observe the problems on their streets and experiment to solve these problems. 7 4 Justice Scalia's concurrence, however, would have the courts give up their responsibility to protect the criminal defendant from disproportionate sentences imposed by overi zealous legislatures Th MERITS AND CRITICISM OF PROPORTIONALITY REVIEW UNDER AN EVOLVING STANDARD Justice Scalia's mode of analysis ignores proportionality principle precedent of the Court. 76 The more ethical and sound alternative to 169. See, e.g., Eddings v. Oklahoma, 455 U.S. 104 (1982) (holding that state courts must examine all mitigating evidence in death penalty cases); Beck v. Alabama, 447 U.S. 625 (1980) (holding that the death sentence may not be imposed when the jury is allowed to consider the lesser-included offense). Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963) (Harlan, J., concurring) (finding that the Constitution does not distinguish capital cases from noncapital cases). 170. See supra notes 90-92, 108-09 and accompanying text. 171. See supra notes 92, 108-09 and accompanying text. 172. See supra notes 90-91 and accompanying text. 173. Solem, 463 U.S. at 290. 174. Id. 175. Harmelin, 111 S. Ct. at 2714 (White, J., dissenting). 176. See supra notes 50-61, 90 and accompanying text. Some members of the current Supreme Court contend that the doctrine of stare decisia should be less strictly adhered to in the area of constitutional law. However, this debate is beyond the scope 1270 CREIGHTON LAW REVIEW [Vol. 25 pure textual and historical eighth amendment interpretation is the "evolving standard" analysis alluded to in Weems v. United States.177 In Weems, the Court argued forcefully for a vital and living interpretation of the constitution when it stated, "[t]he future is [the constitution's] care and provision for events of good and bad tendencies of which no prophecy can be made. In the application of a constitution, therefore, our contemplation cannot be only of what has been, but of what may be.' 7a In Trop v. Dulles, 179 Chief Justice Warren advanced the alternative interpretation and announced that the "evolving standard of decency marked by the progress of a maturing society" determines the progressing content of the eighth amendment. 80 The dissenters in Rummel, Davis, and Harmelin, and the Court in Solem, all recognized the limitations that a purely historical analysis places on a determination of the scope of the cruel and unu8 sual punishment clause in a progressive society.' ' Some members of the Court have criticized the "evolving standard" as standardless and an invitation for judges to make subjective decisions.'8 2 The "evolving standard of decency" is on its face an abstract concept.' 8 3 However, the Court has, with a sufficient measure of objectivity, given substantive content to the occasionally elusive constitutional values of the dignity of man and the concept of human justice embodied in the evolutionary standard.'i 4 In Coker v. Georgia,'85 the Court ascertained perceived societal standards of decency to decide the proportionality of the death penalty for rape. x'6 In its analysis, the Court considered several objective factors, including legislative determinations, history and precedent, the response of juries, and public attitudes. 8 7 The Solem three-prong test has also been used by courts to determine with objectivity what society has considered to be the "evolving standards of of this Analysis. See generally Payne v. Tennessee, 111 S. Ct. 2597 (1991). But see Monaghan, Taking Supreme Court Opinions Seriously, 39 MD.L. REv. (1979). 177. 217 U.S. 349, 373 (1910). See supra notes 50-52 and accompanying text. But see Scalia, 57 U. CIN. L. REV. at 862. Justice Scalia admits, "Perhaps the mere words 'cruel and unusual' suggest an evolutionary intent more than other provisions of the Constitution, but that is far from clear; and I know of no historical evidence for that meaning." Id. 178. Weems, 217 U.S. at 373. 179. 356 U.S. 86 (1958). 180. Id. at 101. 181. See supra notes 71-75, 84-85, 90-91, 118-19 and accompanying text. 182. See supra notes 63, 67, 76-78, 83, 95-96, 103-04, 107 and accompanying text. 183. See supra notes 55-61, 73, 96, 177 and accompanying text. 184. See supra notes 45-46, 56-61, 87-89 and accompanying text. 185. 433 U.S. 584 (1977). 186. Id. at 592. 187. Id. 19921 PROPORTIONALITY decency."' 8 8 Critics have harshly attacked the test, particularly the first prong--comparison of the gravity of the crime and the severity of the sentence.' 8 9 Critics argue that because the gravity of different crimes is an inherently subjective judgment, the personal predilections of judges would unacceptably influence the test.19° Linedrawing between a sentence of twenty-five years and fifteen years in terms of relative harshness, or determining the relative gravity of possession of drugs and burglary, are undeniably difficult aspects of proportionality review. 191 However, two safeguards that have been laid down by the Court assure that proportionality review will maintain a constitutionally acceptable level of objectivity. 192 First, a reviewing court must defer to the legislature in all but rare cases in which disproportionality is found. 193 Therefore, the finite linedrawing feared by critics will generally not be undertaken by judges because these judgments, in which it would be necessary to compare similar terms of years in order to determine the proportionality of a sentence, will be left to the legislature.'i 4 Second, the intra- and inter-jurisdictional analysis of the Solem three-prong test aids in "weeding out" the cases that are not disproportionate. 195 The comparison between sentences in the same state for different crimes and the comparison between sentences in other states for the same crime forces a reviewing court to look to objective indicators of what the political majority considers to be the "evolving standards of decency."'9 For example, if the law of only one state imposes life without parole on a shoplifter, then a judge would be alerted toi 7the possibility of an unconstitutionally disproportionate sentence. 9 JuDIcIAL DECISIONS DRAWN FROM PASSION AS WELL AS REASON The three-prong test is not completely objective, but the law is not an objective creature, and judges, as human beings, cannot inter188. See supra notes 76-77 and accompanying text. 189. See supra notes 79, 104 and accompanying text. In Solem v. Helm, Justice Powell defended the test, arguing that courts traditionally have been called on to make judgments as to the gravity of an offense-there are generally accepted criteria to look to despite the difficulty, and courts are justified in making these judgments. Helm, 463 U.S. at 292-93. 190. See supra notes 87-89 and accompanying text. 191. Rummel, 445 U.S. at 275. 192. See infra notes 193-97 and accompanying text. 193. Helm, 463 U.S. at 289-90. 194. Id. at 290. 195. Harmelin, 111 S. Ct. at 2715 (White, J., dissenting). See supra notes 73-74, 88, 117, 120 and accompanying text. 196. Harmelin, 111 S. Ct. at 2715. 197. Helm, 463 U.S. at 291. 1272 CREIGHTON LAW REVIEW [Vol. 25 pret the law without value-based analysis. 198 Justice William Brennan stated, in a speech delivered to the New York Bar Association: Whether the government treats its citizens with dignity is a question whose answer must lie in the intricate texture of daily life. Neither a judge nor an administrator who operates on the basis of reason alone can fully grasp that answer, for each is cut off from the wellspring from which concepts such as dignity, decency, and fairness flow.L99 More dangerous than the judiciary acknowledging that moral judgment will infuse decisionmaking to some extent, would be the state of affairs in our Nation if courts ceased making challenging constitutional decisions for fear of reaching beyond complete objectivity to make humane judgments." CONCLUSION Justice Scalia's concurrence in Harmelin can certainly be characterized as clear and objective. However, the Bill of Rights was adopted to protect individual rights from the political arena, rather than provide an objective formula for judicial decisionmaking. The rights of the criminal defendant are particularly susceptible to excessively harsh treatment. Protection of these rights is one of the duties of highly respected members of the judiciary whom the Nation trusts to make these difficult decisions. Accepting the mode of analysis applied in Justice Scalia's concurrence, the Court would abrogate its judicial responsibility to protect the individual from a legislature or sentencing judge that in rare instances could impose a disproportionately lengthy sentence on an individual. The proportionality principle requires that a criminal sentence be dignified, decent, and fair in relation to the fault of the offender. The proportionality analysis does require some measure of normative judgment, however, the solution lies in the acceptance of one's humanity, a dedication to a vital and evolving interpretation of the Constitution, and maximum appeal to objective factors to determine the 198. See supra notes 57, 73-74, 189 and accompanying text. See also Brennan, Rea- son, Passion,and "The Progressof the Law", 10 CARoZo L. REV. 21-22 (1988). 199. Brennan, 10 CARDOZo L. REV. at 22. See James, Eighth Amendment Propor- tionality Analysis: The Limits of Moral Inquiry 26 ARIZ. L. REv. 871, 882 (proposing an alternative to the Solem test and recognizing that because proportionality is a retributive concept determining moral culpability, the answer to this moral-based determination cannot be value-free). 200. See Stanford v. Kentucky, 492 U.S. 361, 391-92 (1989) (Brennan, J., dissenting) (asserting that the Constitution contemplated that citizens' rights cannot be left to political majorities, and judges must ultimately determine the constitutionality of a punishment). 1992] PROPORTIONALITY 1273 fairness of a punishment. Whatever mode of proportionality analysis the Court adopts, the proportionality principle contained in the eighth amendment must be preserved as a constitutional guarantee by whomever ascends to the United States Supreme Court in the future. Karen L. Tidwall-'93