wilmabill - The Wilma Theater

advertisement

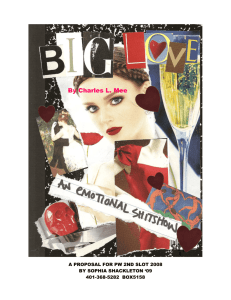

MARCH/APRIL 2004 THE WILMA THEATER Artistic Director Blanka Zizka Newsletter Editor and Dramaturg Nakissa Etemad Artistic Director Jiri Zizka Contributing Writers Susannah Engstrom Nakissa Etemad Managing Director Lynn Landis THE NEWSLETTER OF THE WILMA THEATER Charles L. Mee’s Wintertime: March 10 – April 18, 2004 A Playwright’s Singular Vision of Copyright When one wants to read a Charles Mee play, there is no need to go to a bookstore or library or to contact his agent for a perusal copy of a script. One need only visit charlesmee.org to find almost every play he has ever written. In this day of controversy over copyright law violation through downloading original works from the internet, Mee not only takes the risk of others appropriating his words but actually encourages it. He has entitled the practice: “the (re)making project,” with the invitation as follows: “Please feel free to take the texts from this website and use them as a resource continued, page 2 Meet the Author of Wintertime One of the foremost avant-garde writers working today, author Charles Mee spoke with Wilma Dramaturg & Literary Manager Nakissa Etemad about his work, his life, and the genesis of Wintertime. NE: You had written political history for many years and then returned to writing for theater. Can you tell me about that path? CM: I got out of college in 1960 writing plays. And had stuff done at La MaMa in its very earliest days at St. Mark’s Church in the Bowery, and places like that. And then I got very caught up in antiVietnam War activities and started writing stuff about politics. Which led to stuff about the Cold War, which led to stuff about American foreign policy, and I took this immense detour in life. I stopped writing for the theater altogether and wrote political history for 20 or 25 years and only got back to writing for the theater again in the late ‘80s. But the theater had always been my great love, really. NE: Do you think there’s a quality in both history and theater that connects your love for them? Mee’s writing takes inspiration from collage artists of the 20th Century. Bottom Photo: Man Ray. CM: I don’t think of it so much as the two things appealing to the same impulse as that I come back to writing for the theater with a different sense of things than I think originally I had. That is, it seems to me that human beings are formed by history, not just by the psycho-dynamics of early childhood. Charles L. Mee And so the people I put on stage, I hope in some way, their behavior is explained a little more broadly than just by psychology but includes history and culture and gender and genetics – all of those things that we really know are true. So it’s a broader, more open understanding of what it is to be human, I hope, and that’s what I think I bring to [the theater] from having spent all those years writing history. NE: How does playwriting compel you in your life now? CM: The truth is, when I was a kid, the first play I ever saw – my mother took me to see the musical South Pacific. And there was an actor who had a big sailing ship tattooed on his stomach – sailing ship on the water, on waves – and he continued, page 2 open stages 2 Playwright’s, cont. from page 1 for your own work: cut them up, rearrange them, rewrite them, throw things out, put things in, do whatever you like with them – and then, please, put your own name to the work that results.” (Of course, to produce his work as written, one must obtain rights as with any other playwright’s work.) This unusual practice of “(re)making” is due in part to his philosophy of original writing. Here is an abridged version of his introduction from his website that says it all: There is no such thing as an original play. None of the classical Greek plays were original: they were all based on earlier plays or poems or myths. And none of Shakespeare’s plays are original: they are all taken from earlier work. […] Sometimes playwrights steal stories and conversations and dreams and intimate revelations from their friends and lovers and call this original. “the culture writes us first, and then we write our stories.” And sometimes some of us write about our own innermost lives, believing that, then, we have written something truly original and unique. But, of course, the culture writes us first, and then we write our stories. […] And so, whether we mean to or not, the work we do is both received and created, both an adaptation and an original, at the same time. We remake things as we go. […] I think of these appropriated texts, [my plays on this website], as historical documents – as evidence of who and how we are and what we do. And I think of the characters who speak these texts as characters like the rest of us: people through whom the culture speaks, often without the speakers knowing it. And I hope those who read the plays published here will feel free to treat the texts I’ve made in the same way I’ve treated the texts of others. Meet the Author, cont. from page 1 could make his belly roll in a way that made the ship rock on the waves. And I think that’s when I fell in love with the theater. And so I grew up to be a more sort of serious person writing all this political history, but I think in some way the seriousness of that world combined with the ship rocking on the waves is what I never tire of. And so I get up in the morning every morning and get a cup of tea and come to my desk, and there’s just something I always want to work on. And it’s this source of endless pleasure for me. It’s like there’s no solution to playwriting. I guess maybe mathematicians get up in the morning interested in doing another problem, too, but, to me, the world of the theater is this infinitely variable set of fascinating human beings that just I never tire of. NE: What was the inspiration for the story of Wintertime? CM: Well, several years ago a director named Ken Watt who had done my version of Orestes in San Francisco called and asked if I would write something for him to do in San Francisco. And I thought, “Oh, great. I mean, he loved that twisted, nasty Orestes, he’d like me to do something really twisted and horrible. And I don’t know anybody in San Francisco, I don’t have any friends there so I can do something really awful.” And so I set out to do a really awful, twisted, nasty piece of work. And out came this kind of frothy romantic comedy called Summertime. And I didn’t quite believe it but I sent it to Ken, and he didn’t believe it at all. So he tried to surface deep, dark, awful stuff from the subtext. And I went out to see this workshop, and I said to him, “You know, I don’t think you can do this, I don’t think you can sort of load King Lear on top of a frothy comedy without sinking the whole deal.” And he said, “Yeah, I think you’re right.” So he turned it upside down, and he did this nice little romantic comedy. But I watched it and I thought, “But I could do that. I could surface the dark stuff and call it Wintertime.” “I love theater that takes me someplace I’ve never been – whether that’s to some really foreign land or just to some other place in the human heart.” So I set out with the same people in the same summer house but in the middle of winter to do this really dark play. And out again came this romantic comedy. So I’ve sort of given up on the dark, twisted play. But beyond that, I guess Wintertime is sort of full of my life.… You know, a lot of times I’ve taken a classical model, or I’ve taken something and deconstructed it and appropriated Notes Toward a Manifesto Written by Charles L. Mee in 2002 If Aristotle was right that human beings are social animals that we create ourselves in our relationships to others, and if theatre is the art form that deals above all others in human relationships, then theatre is the art form, par excellence, in which we discover what it is to be human and what it is possible for humans to be. Whatever else it may do, a play embodies a playwright’s belief about how it is to be alive today, and what it is to be a human being – so that what a play is about, what people say and how things look onstage, continued, page 8 Cover of the First Edition of Mee’s autobiography, design by Leslie Goldman. 3 open stages material and stuff. But this play actually comes completely from my life. Which is to say, none of the characters is exactly a character – nobody is me, or a friend of mine, but sort of scraps and shards of my life and friends. Or bits of them coalesce in different ways and those become new characters. So to watch it is kind of wonderful for me because I see my life flashing before my eyes in this odd, remade way. NE: How do you think Wintertime falls into your canon of plays? CM: I guess, just in those terms, probably half my plays begin as being material stolen from somebody else, and half of them are original – which is to say, stolen from wives and friends and family and…. But in another sense, I think that my earlier plays, many of them derived from Greek tragedies, were horrible, nightmarish kinds of plays. And my work in the past several years or so has taken a turn into a sort of happier world – because my life has; I’m just a happier person. And so there have been a lot of plays about love, and a lot of plays that have some kind of sweetness to them – not because I’m a sweet person but because I maybe have encountered sweet people, or longed for it. But I think Wintertime, in some way, combines a little bit of both of those worlds…. I was thinking of Molière a lot while I was writing it, this kind of beautiful thing that Molière does of sort of floating a nice comic world and then having these dark threads that run through it, or threads of melancholy or sorrow or regret or heartbreak or whatever else it may be. So that it feels [like] it combines a little bit of light and dark at the same time. NE: You developed part of Wintertime at Sundance Theatre Lab with Les Waters as the director, who then directed it at La Jolla Playhouse and then at Long Wharf Theatre. Did you follow any subsequent productions? CM: No. […] But I’m a guy who almost never goes to rehearsals anyway. (NE: Do you not enjoy it, or...?) No, no, I actually love it. But I feel that the director and the actors should be as free to do their thing as I was to do mine. And I feel that when a playwright is in the room, everybody thinks the Watercolor by Ted Kautsky. definitive version of this play exists in his head, and if we can just find out what that is and replicate it exactly on stage, we’ll have done the right thing. But I don’t think there is such a thing as a definitive version of anything. And so I think if the actors feel a little freer to just explore and find out for themselves who these people are, they have a great deal more vitality and spontaneity, and they become who they are going to best become in that play. So I think getting out of the way is really crucial. I think I’m the only playwright who believes that, but I really believe that by staying out of rehearsals I get better productions. […] It occurred to me some years ago that the playwrights who got the best productions were the dead playwrights, and maybe that was because they didn’t go to rehearsal. NE: Our audiences saw Big Love last season. Big Love is your response to a classic, whereas Wintertime is an original piece. In your opinion, how is Wintertime different or similar to Big Love? CM: Well, I think it’s a very different play. I mean the same person wrote it, so it’s the same person concerned with the issues of how people get along and whether they’re kind or cruel or selfish or generous or any of those things. I guess I think, in a way, Big Love was really all about young people dealing with relationships – for the most part anyway. And Wintertime feels to me more like all the generations. So there’s this young love that sets it off, but then it’s not just a question of whether two young people are going to find true love, it’s a question of whether a marriage of some years can be sustained, or if not, different sorts of relationships between grown-ups can work.... So I guess that’s the main thing. NE: Having seen our production of Big Love, is there something you’re curious about or expecting with our production of Wintertime? CM: Well, I don’t know what to expect. I thought the production of Big Love was really wonderful. And I think Jiri is amazing and brilliant. And so I’m just excited to see whatever he does. NE: What do you personally love most about the theater? CM: I love theater that is terrific fun and very challenging both to the heart and the mind, that’s completely involving, and that takes me someplace I’ve never been – whether that’s to some really foreign land or just to some other place in the human heart. 4 Designing Mee: Meet the Designers of Wintertime Wilma Dramaturg & Literary Manager Nakissa Etemad had the delightful opportunity to talk to those creators who live behind the scenes and work their magic in images rather than words, the designers whom we rarely get to hear from, as their products speak for themselves. The design team for Wintertime happens to be the same team that designed last season’s Big Love, also by Charles L. Mee and directed by Jiri Zizka. Set Designer Jerry Rojo, Costume Designer Janus Stefanowicz, Lighting Designer Jerry Forsyth and Sound Designer Bill Moriarty discuss the design process and share their impressions of Charles Mee and his work. Setting a World of Ideas NE: Talk to me about the work of Charles Mee. Jerry Rojo: It is to me the best kind of theater, what the stage is all about. Wintertime has much more traditional dialogue, and the scenes are about people who talk and express themselves, and I think it’s more Chekhovian in that way, or Pinteresque. My first impulse after having read Wintertime for the first time was the birch trees. They have this lyrical and romantic quality to them, and if it’s a birch tree forest, then it can be dangerous at the same time. And because the play is [taking place in] the winter, it can have a number of urges to it that one can play on or off of as the play proceeds. NE: How is it different for you to design a Charles Mee play versus another more traditional playwright’s work? Initial Concept Sketch of Wintertime Set Design by Jerry Rojo. Insert: Rojo’s Scale Model of the Set. open stages JR: It’s much more of a process between the director and the designer. Jiri and I have been working on this since September, and it still isn’t over. Things are still evolving, and we’re still looking at some questions. It never ends because you think you’ve solved this problem – then we do something else, and that impinges on [our first solution] and we have to make changes… So it takes a long time. Whereas in a traditional play, it’s all pretty much spelled out. A lot of directors I’ve worked with see theater as words for actors and hope that the designer does a nice background, and that’s about the end of it! The Wilma tends to do so much with lights and sound and scenery and all of that… that’s how they perceive the theater. And that to me is the best kind of theater. NE: After having designed over a dozen shows at the Wilma, both you and the theater seem to have found a good fit. Does a philosophical writer like Charles Mee inspire you in a certain way? 5 JR: Yeah, he does, because I think he’s a writer who has a certain theory of art: that there can be no art without ideas… Now I don’t believe that plays should be didactic…Mee is probably less message-oriented than say Brecht, for example, but boy, for me, Wintertime screams out a message! In one of the first lines of Wintertime, Francois says something about America, that people misunderstand each other, that no place else do they do that. So early on in the play, Mee I think is telling us this is about America – it’s not about [certain] people, this is how America does things.… I think it’s how we have a double standard on sexuality, for example, and that’s why Francois, the Frenchman, and Jacqueline, and these exotic characters are in there because it pits them against our American sensibility, where we have happy endings and romantic young women and lovers and all that stuff. […] He also talks about us as a mercantile, industrious people…and we get too involved in so many other things, we don’t think about ourselves, we don’t think about each other. So I do believe that’s the main theme in the play, how people relate. It’s one of the best relationship plays I’ve ever read. It’s all very true, very real but done in a very entertaining way. And he kind of forces us to look at ourselves. Charles Mee is one of my favorite playwrights. Nobody brings stagecraft and idea in such clarity the way he does. NE: How was the Big Love experience for you? JR: It was phenomenal. It was very process-oriented and it meant a lot of meetings. In the process you can’t just e-mail, you have to sit down and talk and bring stuff to the table – literally, look over pictures and this kind of thing. And that’s how that came together. And I thought that production was about as good as you can get it. In the last analysis, it was a very joyous experience when I look back on it. Clothing Individuality open stages JS: Exactly. I would say it’s one of my favorite things about working at the Wilma, being able to work with the same people over again. NE: How was the Big Love experience? Carmen Roman and Danielle Langlois in last season’s Big Love. NE: When you’re focusing on clothes, how do the words of the play influence you? JS: Oh, it was terrific. And I got a big prize for it, [the 2003 Barrymore Award for Outstanding Costume Design]. I mean it doesn’t get any better. I have to say though, one thing I think that is particularly inspiring about Charles Mee’s writing [is that it offers something] that not all writing does: the non-realistic setting that inspires the sculptural ideas that Jerry Rojo creates. I think that’s really exciting to me, to be in that kind of environment. That our world starts with something that is so creative, that isn’t just three boxy walls. If you do more realistic plays, they have to have more realistic sets. And I just think of that Big Love set…and then I’m sure this one will just be wonderful pieces of art. And then it’s great to be able to have your design on top of it, and lit by a good lighting designer. continued, page 6 Janus Stefanowicz: Basically I need to have the costumes imply character. It’s hard to have a costume imply a word. But we can have it imply a kind of character, without being stereotypical but yet being familiar, for us to recognize that type of person. If you see someone, a young girl in a miniskirt, as opposed to a young girl in all black clothes, you get a different view of two different kinds of characters. But of course, we get who the character is from the written word. And Mee’s characters are very much individual characters. NE: What is it like to design with the exact same team from Big Love? JS: Oh, it’s terrific. I just think that communication is the basis of any good design, and the more you work with the same people, the more you understand what everyone means by a certain word or a certain phrase and what the need is. And it only becomes a tighter unit when you work together multiple times. NE: Is that something that makes you enjoy working at the Wilma so much? Paolo Andino and Danielle Langlois in Big Love. open stages 6 Danielle Skraastad, Amy Gorbey, Carmen Roman, and Danielle Langlois in Big Love. Designing Mee, cont. from page 5 Shedding Light on Surreality NE: How is it different designing a Charles Mee play versus a more traditional playwright’s work? Jerry Forsyth: A Charles Mee play tends to have a secondary layer. There’s a basically realistic portion and then there’s usually an out-of-reality or a heightened-reality moment that interjects. So, for me, one of the first things with a Charles Mee play is trying to identify those non-realistic sections, and determining what he’s trying to say with them and how to treat them in a way that points them out without calling attention to the technical aspects. NE: What does it feel like doing another Charles Mee play here with the same design team? JF: We didn’t have to start from ground zero. We have developed a way of working and sort of a visual vocabulary that I thought would be particularly useful. However, this is such a different animal – it is still a Chuck Mee play and has many of his characteristics, but its world view is a little different. Big Love seemed to be dealing with larger issues almost the whole time. There were some realistic sections but it really did seem to be a state-of-the-world comment throughout a majority of the play. Whereas Wintertime has flashes of that but is predominantly reality-based, or a drawing room comedy with moments of Charles Mee peeking through. So I think it’s useful having the same design team dealing with a second work by the same playwright. NE: How was the Big Love experience for you? JF: Different but good. Everyone likes to toot the collaborative horn, but I usually like going into a show knowing at least what my world is for the play and how I’m treating it. And Big Love was such a wild card that more than usual I needed to go into it with a paint box of tools to choose from to alter the space. And then a lot of decisions were reached in technical rehearsals, generally between Jiri, Jerry Rojo, and myself. So that was initially worrisome and in the end a very pleasant experience. NE: What brings you back again and again to the Wilma, and to working with Jiri? JF: Well, to a great extent that is the answer, working with Jiri. The Wilma has the resources to challenge a designer. […] At the Wilma, it is more about what you want to see as opposed to what you have the ability to put on stage. And, talking about working with the same design team again, having 17 years now with Jiri, you learn how the other collaborator works, and it sometimes makes it more interesting. You have a sense of the way a director likes to work. Reinforcing Mood with Sound NE: How is it different to design sound for a Charles Mee play versus another more traditional playwright’s work? Bill Moriarty: I’ve found there’s not a lot of realistic sound effects, of realistic reinforcement of mood. He calls for a lot of specific music and specific recordings of traditional classic work. And as opposed to some sort of music subtly coming in and reinforcing the background, there’ll be a moment in the play where there’s a shift in emotion, and we just accent that emotion by turning the music up incredibly loud – or as [Mee] calls for, “deafeningly loud.” It’s not a subtle thing, it’s the human emotion that’s changing, and everything about the play’s going to change. NE: Is there any liberty? Do you add other sound effects? BM: Absolutely, yeah. This particular play Wintertime is much more about mood than actions. The last play we did, Big Love, had some huge things happening with the helicopters and people coming in from different places and then the murder scene. This is more just really showing and changing the human emotions. NE: Does the fact that Mee is a philosophical writer inspire your design in a certain way? open stages 7 BM: It’s completely human. I find this playwright to be talking about people and the way people feel, the strange things that people do and are driven by. I come from that place with the music or tones to try and show the different sides of what a human can do. Words from the Actors of Wintertime Considering Charles Mee’s terrifically theatrical style, his poetic language and no holds barred physicality, one might wonder – what must it be like to act in a play by such a writer? And what might draw an actor to this kind of theater? To answer these questions, Literary Assistant Susannah Engstrom spoke with the Wintertime actors a few weeks before the first rehearsal. While some actors had worked on a Charles Mee play before (three were in the Wilma’s production of Big Love) and some actors’ sole exposure to the writer was reading Wintertime, all had something to say about the delights and challenges of bringing Mee’s work to life. What draws you to Charles Mee’s work? I think there’s something visceral, insane, delightful, bizarre about Chuck’s plays…. I threw saw blades last year in Big Love and obviously that’s not something you’re going to do [regularly], but that scene was completely a logical extension of the frustration that was happening for the men in that play.… I think [Mee explores] things in a totally unexpected way. I think he creates insane moments but they still capture the way people either behave or want to behave. possible in terms of love and lust and desire and trust. • ELIZABETH HESS (MARIA) I really like his writing. It’s very poetic and very touching and at the same time it’s really funny. It’s amazing how he can do both at the same time. I also like [Wintertime] because there’s a lot of action and conflict and a lot of hijinks, and it seems like it’s going to be a fun thing to work on. • PRUDENCE HOLMES (BERTHA) [Mee] is not afraid to go beyond the bounds of conventional theatricality. A lot of theater you see today would do just as well on television, and it’s really nice to see something that wouldn’t work on TV. • SETH REICHGOTT (EDMUND) Chuck Mee’s work seems to literally pull me straight from the heart. The passion it emotes balanced by a very strong earnest base really attracts me to return again and again. Excitement lies in the privilege of putting life into an already lively play. And everything’s so huge! And that’s the way human emotions feel – huge! But we subdue those huge feelings in everyday situations and act according to our subdued environments. • JULIANNA ZINKEL (ARIEL) • MICHAEL EWING (JONATHAN) I think [Mee] knows an awful lot about all the permutations of love. He seems very savvy to me about love. Maria, I feel, is caught between domesticity and deliciousness, and I think that’s a common plight for an awful lot of people, and I find it completely compelling… I really feel like [Mee] has a deep experiential understanding of the layers of what’s Ice Sculpture as the centerpiece for a wedding. He has a way of bringing forth many, many, many societal taboos – such as adultery, a mother’s sexual attraction for her son, homosexuality, you name it, things that are considered on the fringe and/or not acceptable in this society – and presenting them in such a way that there’s enormous respect given to each of those lifestyles, or points of view, or sexual orientations.… • DALE SOULES (HILDA) I like that he’s always searching for a bridge between lovers.… He takes these extreme, hidden-away lovers that nobody sees and nobody knows, and he makes them exist and try to find love. And their grand attempt at it makes our struggle seem more clear. • DANIELLE SKRAASTAD (JACQUELINE) continued, page 8 open stages 8 Words, cont. from page 7 Prior to reading Wintertime online in preparation for auditioning, I had never seen or read a Chuck Mee play. I realized in no time at all that he’s a major dramatist. For me, with his concise poetic language and confident use of illustrative symbols and symbolic actions, he creates a stark, very singular world where some very human creatures come to terms (or don’t!) with their various struggles. • JOHN WOJDA (FRANCOIS) truth in all of that. And I suppose you could also say the other way around – to not get buried by the truth.… So both to be able to dig down and be able to come back up again. • ELIZABETH HESS (MARIA) Perhaps it’s the creation of this ‘special world’ of Mee’s that allows the characters in Wintertime to be so believable on the page. The challenge for the actors, then, is to make the characters as believable in the playing as they are on the page – no mean feat! • JOHN WOJDA (FRANCOIS) What are the challenges you face as an actor preparing for a Chuck Mee play? I think one of the big challenges is to find the tone of the piece without losing the truth. When I first read the play I thought, this guy has as much insight in his own way into love as someone like Ingmar Bergman does in his way, and it would be such a shame not to find the Notes Toward a Manifesto, What about the physicality of Mee’s work? We tear our hair out over the complexities of love, but there’s also something so wonderful about [Mee’s] levity. That physicality is just a great way to keep it in perspective. I think smashing things is such a human inclination. • MICHAEL EWING (JONATHAN) I’m a big fan of physical comedy, so any time you can bring that to a show I think not only do the actors enjoy it but I think the audience does, too. • GREG WOOD (FRANK) I love the physicality of Chuck Mee’s work. It makes me feel very comfortable…. I am a very kinetic person by nature and emotion affects me physically, so I think I understand what Chuck Mee is getting at by the physical scenes; it’s when words just don’t or can’t do, it’s when stuff just comes out through your body, and you gotta throw it down, or squeeze it tight, or shove it into the next tree. • JULIANNA ZINKEL (ARIEL) • ELIZABETH HESS (MARIA) cont. from page 2 and, even more deeply than that, how a play is structured, contain a vision of what it is to have a life on earth. If things happen suddenly and inexplicably, it’s because a playwright believes that’s how life is. If things unfold gradually and logically, that’s an idea about how the world works. […] When I had polio as a boy, my life changed in an instant and forever. My life was not shaped by Freudian psychology; it was shaped by a virus. And it was no longer well made. It seemed far more complex a project than any of the plays I was seeing. And so, in my own work, I’ve stepped somewhat outside the traditions of American theatre in which I grew up to find a kind of dramaturgy that feels like my life. […] In 1906/07, Picasso stumbled upon cubism as a possible form. Immediately, he made three pencil sketches of a man, of a newspaper and a couple of other items on a table, and of Sacre Coeur – that is, of the three classic subjects of art: portraiture, still life, and landscape. And he proved, to his satisfaction, therefore, that cubism “worked.” My ambition is to do the same for a new form of theatre, composed of music and movement as well as text like the theatre of the Greeks […] – Excerpts, from “Mee on Mee,” The Drama Review 46, 3. Paolo Andino and Danielle Langlois have their first dance in last season’s Big Love.