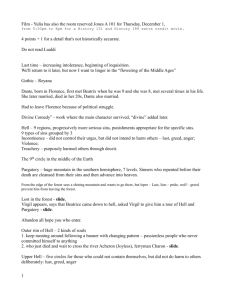

THE INFERNO DANTE ALIGHIERI Cantos I–II Summary: Canto I

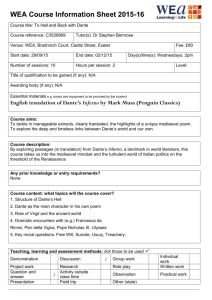

advertisement