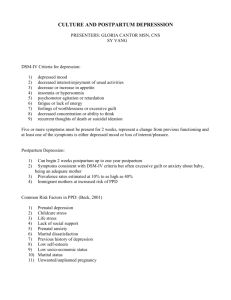

Postpartum Complications

advertisement