pdf - Fondazione Internazionale Menarini

advertisement

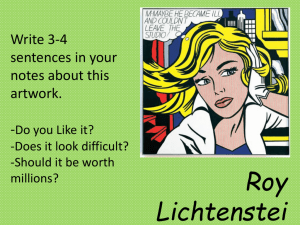

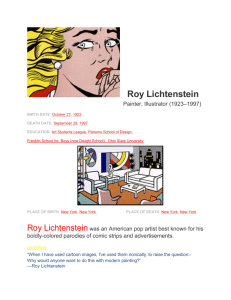

n° 368 - January 2015 © Tutti i diritti sono riservati Fondazione Internazionale Menarini - è vietata la riproduzione anche parziale dei testi e delle fotografie Direttore Responsabile Lorenzo Gualtieri - Redazione, corrispondenza: «Minuti» Edificio L - Strada 6 - Centro Direzionale Milanofiori I-20089 Rozzano (Milan, Italy) www.fondazione-menarini.it Much More than a Comic A journey through Roy Lichtenstein’s Pop Art at Turin’s GAM Contemporary man is constantly surrounded – and at times steamrolled – by images; modern technologies permit immortalising and reproducing any fragment of life, making each unforgettable, frozen in time – but also a simple drop in an ocean of indistinguishable drops. The image has always been used to preserve memory, initially the memory of the world of spirituality and power; it gradually became a common heritage and then what it is today, a mass consumption commodity found everywhere: in product logos, news, ads and media in general. By the 1950s, a strong change in the value of the image – and consequently, of art – was perceivable, first in the U.K. and then – and above all – in the U.S., where the phenomenon denominated Pop Art got its start. It began as a repudiation of the excessive intellectualism of Abstract Expressionism; it drew its strength from common ‘wares’ available to everyone at any time: advertising, comics, news, all types of everyday products, from soup to laundry soap. The term ‘Pop Art’ derives from the word ‘popular’ in its sense not of ‘trendy’ but of ‘mass’. Pop Art did not seek to provoke, as had Dada, nor to communicate a social message; it did not aim to stimulate rebellion of any kind. More than anything, it was the reflection of a changing world, of new production methods, of the rise of a new consumer society, of an age in which any object whatsoever can be (re)produced in series – all without critical or alarmist intent. Rather than to abstract from the new reality, it instead tried to include it in the world of art and by doing so created new categories, new forms of availability: art must keep in step with the times and become a mass phenomenon, no longer an enjoyment for a few but the narration of the stories of everyone, from the labourer to the rich industrialist, from the seamstress to the high-fashion stylist. Independently of each other, Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol launched Pop Art in the U.S., drawing inspiration from tabloid cartoons and advertising. From characters loved by comic-strip readers, Mickey Mouse and Popeye became works of art; the very titles of Lichtenstein’s creations sound ‘comic’ – or better, onomatopoeic: Takka takka, Varoom, Crak, Whaam! – and it seems that the canvas itself is shouting them. This new art encountered strong opposition, since it seemed almost to provoke, to critique the emotional depth of the Abstract Expressionists’ canvases: the more traditional critics, who had barely had time to digest the novelties of Pollock’s drippings, did not appreciate this emerging trend in artistic production and did not hide their disappointment. A 1964 Life magazine article on Lichtenstein was titled ‘Is he the worst artist in America?’. The borderline between art and design became very thin as Pop Art advanced – and criticism pulled out all the stops; for example, it formally charged ‘banality’. This was by no means the first time the art world had pilfered from mass culture, but until that time this tactic been employed to temper overlyserious contents with spunky low notes; Pop Art, on the other hand, seemed to do the opposite and make the commonplace object the undisputed protagonist. Lichtenstein was accused of blatantly copying the comics and therefore of lack of originality. Nothing could be less true, however, since his ‘copying’ was a complicated process. The artist carefully selected one or more panels from a comic strip and made sketches which he then Study for Pop! - Marsha and Jeffrey Perelman Collection © Estate of Roy Lichtenstein / SIAE 2014 page 2 Still Life with Mirror (Study) - Private collection Oh, Jeff...I Love You, Too...But... (Study) - Private collection © Estate of Roy Lichtenstein / SIAE 2014 © Estate of Roy Lichtenstein / SIAE 2014 transferred to canvas without ever reproducing the strip or the panel as a whole; after tracing the image on the canvas and adapting it to the picture plane, he filled it in by stencilling on dots in primary colours and added heavy outlines to give prominence to the figures; he began painting from the light ground and then went on to the black outlines. Despite appearing to be simple reproduction of normal comics, his work was actually a study and an accurate union of mechanical reproduction and handwork – and it is indeed difficult to distinguish the two. Perhaps Lichtenstein’s technique should be considered the cry of a man who felt oppressed by the modern technologies and who attempted to imitate them, first placing himself on their level and then improving on them. The artist took an interest in studies of visual perception throughout his career; he ‘poached’ the Ben Day dot from industrial typography and made it his highly original signature; he did not use his dots as in Pointillism, to create a homogeneous appearance at a certain distance, but rather used a typographic overlay of exaggerated dimensions to convey the idea of a print. The inventor of the Ben Day Rapid Shading Mediums was Benjamin Day, who by 1878 had excogitated an ‘industrial’ application for the optical principles formulated by the 19thcentury colour theorists. But the sensational, innovative character of the Lichtenstein dots derives from the interpretation of reality they convey: a sense of radical change, that life itself was mediated, ‘screened’, by the appalling bulk of printed and transmitted images. Liechtenstein once ironically commented, ‘In almost half a century of career I painted comics and dots for only two years. Is it possible that no one has ever noticed that I have done nothing else?’; and indeed, to see Lichtenstein’s entire oeuvre solely as a collection of dots poses a serious limit to understanding his work. To overcome this obstacle, from 27 September 2014 until 25 January 2015, Turin’s Gallery of Modern Art (GAM) is hosting a total of 235 works by Roy page 3 Lichtenstein which illustrate how he adopted and evolved the Ben Day technique over the course of his creative life, drawings from the early Forties to 1997, several large works and documentation in the form of a photo exhibit of the artist at work. The exhibition, curated by Danilo Eccher, Director of GAM Turin, centres on Lichtenstein’s Opera Prima (First Work); that is, the origins of his work, his sources of inspiration, his sketches and studies – and only then moves on to the finished paintings. The works on show reveal the world of fantasy and dreams latent in Lichtenstein’s canvases – as in those of Miró and Dalí, from whom the artist seems to draw inspiration in certain of his drawings: eyes in a cloud or in an ear, figures broken up, not only in the terms of technique, which makes use of lines and dashes more than dots, but also physically: mouths placed vertically and objects endowed with unbelievable malleability and fluidity suggest that Lichtenstein intends to compose rebuses with his figures; at the origin of his work we thus see references to Surrealism and Dada, albeit more for study and research than for social reasons; he explores the forms but ignores the messages; his is pure creation. It is easy to yield to the temptation to consider Lichtenstein a mere imitator. But he was much more: far from simply imitating, his art draws inspiration from the visual world shared by the masses and proceeds on to something higher, to true artistic representation of subjects considered ‘banal’, succeeding in elevating them towards pure abstraction. Often, contemporary art presents figures which dissolve into the background to abolish depth and make surfaces completely flat. Lichtenstein, like the other Pop artists, instead gives us the illusion of space and the de facto reality of the surface, as though the comic-strip characters had usurped the metaphysical space of Malevich’s geometric figures. Before landing on the shores of Pop Art, Lichtenstein experimented with an Expressionist style, then with a faux folk style to which he adapted American themes and, for a short time, with abstract compositions. He mastered, without difficulty, a series of devices of the modernist schools and the artifices of the avant-gardes, such as the gestural brushstroke for laying on a shadow or a white spot for a reflection, the abstract forms of the grid, monochrome painting, ready-made, the found image. All held together, in his works, by the subjects inspired by advertisements and comics, by that figurative mode which avant-garde art had attempted to overthrow. In 1967 he stated, ‘I don’t draw a picture to reproduce it – I do it in order to recompose it. Nor am I trying to change it as much as possible. I try to make the minimum amount of change . . .’ And here is the kernel of Lichtenstein’s creative approach: to replicate printed images but adapt them to pictorial parameters. Picasso, Matisse, Mondrian and Léger are all present in his canvases, read through comics: the ambiguity of Picasso’s light and shadow, Mondrian’s primary colours, Léger’s semi-caricatural figures, Matisse’s marked, suave contour. A propos of his own pictorial language, Lichtenstein once remarked, ‘Mine is linked to Cubism to the extent that cartooning is. There is a relationship between cartooning and people like Miró and Picasso which may not be understood by the cartoonist, but it definitely is related even in the early Disney’. Enquiry into Lichtenstein’s Opera Prima is essential to understanding the artist’s development, what led him to make certain choices and how he breathed life into what we might call a democratisation of art – which continues yet today. elena aiazzi Study of Hands - Private collection © Estate of Roy Lichtenstein / SIAE 2014