excerpt - School for Advanced Research

advertisement

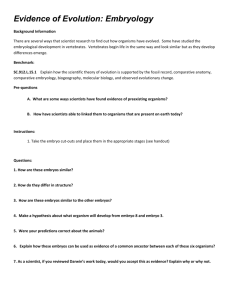

Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 261 9 Embryo Tales Lynn Morgan Today it is commonplace for human embryos and fetuses to speak to all manner of social issues. In addition to declaiming on the well-worn subject of abortion, embryos and fetuses help advertise cars and telephone service, have vehement reactions to vaccine and disease research, justify the incarceration of pregnant women, motivate workplace safety legislation, and hold forth on a host of other issues. They are, in short, active agents. Feminist scholars have been concerned about the rapid proliferation of “fetal subjects,” especially because the focus on fetuses threatens to curtail reproductive options (Morgan and Michaels 1999). Feminists have often identified modern visualizing technologies as one of the crucial elements in the creation of fetal subjects, arguing that ultrasound and amniocentesis permit some people to assign attributes of personhood to the unborn.1 There is no question that the proliferation of visual images since the 1970s has sparked a dramatic increase in Copyrighted Material www.sarpress.org 261 Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 262 LY N N M O R G A N the subjectivity recently granted to embryos and fetuses. In this essay, I argue that human embryos were invoked as political actors and agents as early as the 1910s and 1920s, when a new visualizing technology allowed embryologists to describe embryo forms and composition in unprecedented detail and thereby to attribute innovative meanings to human embryos. Yet the images of embryos that scientists produced during that time did not immediately result in personification of the embryo, nor did they much influence attitudes toward abortion, which was by then already illegal in all states. Although today we tend to associate visual images of human embryos and fetuses with the politics of abortion, I argue that the meanings ascribed to such images vary depending on the context in which they are visualized. I want to denaturalize the human embryo by showing that visual depictions of it were not always considered relevant to abortion or reproductive politics. This finding suggests that embryos do not take their meanings from immanent qualities. Embryos do not themselves pose conundrums or create disputes; rather, social controversies provide the interpretive lenses through which embryos are imbued with meaning (Addelson 1999). Taking the contemporary feminist concern with the animated fetal subject and projecting it backward to the 1910s and 1920s, I inquire in this chapter about the circumstances in which embryologists first coaxed their specimens to speak. In the waning years of the nineteenth century, a small group of human anatomists began to take an interest in human embryos.2 By appealing to their clinical colleagues, they painstakingly collected and preserved miscarried embryos and fetuses. They used the newest visualizing technology of their day, the microtome, to produce models of the human embryo from the earliest, hitherto unknown stages of development. With the scientific tools at their disposal, they began to craft a tangible entity that had long been imagined but rarely seen and never systematically studied. 262 www.sarpress.org Copyrighted Material Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 263 E M B R Y O TA L E S By producing visible evidence of the embryo’s contours and dimensions, the embryologists set the stage for major epistemological and ideological shifts. They claimed human gestational development as a biomedical enterprise, the embryo itself as a neutral biological product, embryo collecting as a valuable, legal, and ethically justifiable enterprise, and themselves as experts in a new professional specialty. From today’s vantage point we can see that the embryologists worked to collapse the distinction between “the way a thing is made intelligible [and] the thing itself” (Stormer 2000:109). They claimed that they could interpret embryos accurately and dispassionately by looking at the material evidence. Embryo specimens, they were certain, would carry their meanings intact and “speak for themselves.” As embryos began to enter public conversation in the 1910s and 1920s, the range of topics to which they were considered relevant was much different from what it is today. Most strikingly for our purposes, the embryo specimens were not considered pertinent to the social problems of abortion, illegitimacy, and contraception, all of which were nevertheless pressing issues at the time (Chesler 1992; Fee 1987; Gordon 1976). Embryos were hitched to an entirely different set of social problems, namely, evolution, the “race problem,” and the relationship of humans to nonhuman animals. In this chapter I explore how the embryos got recruited as evidence in these particular social dilemmas. I conclude that embryos are discursively produced within particular social dramas and hence are not automatically or naturally associated with abortion or reproductive freedom, as is so often assumed today. A WORD ABOUT SEMANTICS The favored term for the product of conception in the early twenty-first century is “fetus,” although the word, like its referent, is controversial. Antiabortion activists prefer “unborn child,” “preborn,” “our little friend,” and so on, because “fetus” is too clinical to confer the sympathetic Copyrighted Material www.sarpress.org 263 Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 264 LY N N M O R G A N appeal they seek. Pro-choice activists note that the term “fetus” is often applied inappropriately throughout the whole course of pregnancy, thereby collapsing the physiological and, presumably, moral differences that distinguish a zygote from a ten-week embryo and a thirty-seven-week viable fetus. Celeste Condit (1990) pointed out that abortion opponents have worked hard to forge a rhetorical connection between the term “fetus” and an arresting visual image of the late-term fetus, thereby ensuring that “fetus” performs antiabortion service. In spite of such terminological disputes, “fetus” has been the preferred term because it is considered more neutral than other options.3 Early in the twentieth century, the term of choice was “embryo,” although its use, too, was inconstant and controversial. In formal scientific contexts, embryologists used “embryo” to refer to the developing human during the first eight weeks of gestation, but in their correspondence and publications they often used it to refer to all stages of development. A striking example of slippage between the terms embryo and fetus is evident in the catalogue for the socalled human embryological collection amassed by North American anatomists at the Peking Union Medical College in the 1920s. According to the catalogue, the collection in 1925 contained 358 Chinese specimens, of which 254 were normal (i.e., not obviously pathological). A closer look at the list reveals that only 7 of the normal specimens were embryos, whereas fully 239 were fetuses and 8 were infants (Fortuyn 1927:68). Calling it an “embryological collection” inflated its status (and the prestige of its producers) at a time when anatomists coveted and cherished bona fide human embryos. In this and many other contexts, the terms embryo and fetus were actively contested throughout the early twentieth century, much as they are today. COMPOSING AMERICAN HUMAN EMBRYOLOGY In 1883, a young American anatomist, Franklin Paine Mall (1862–1917), traveled to his parents’ home country of 264 www.sarpress.org Copyrighted Material Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 265 E M B R Y O TA L E S Germany to study anatomy. There he encountered Wilhelm His, who was intent on transforming embryology into a systematic science (see Hopwood 2000). His had begun to collect and study that rarest and most precious of anatomical specimens, the young human embryo (which he lovingly called “fruit”). When Mall became intrigued with the project, His presented him with two human embryos to take home. Mall brought the little immigrants to the United States in 1886 and immediately began to augment his collection by asking his clinical colleagues to preserve any embryos or fetuses they might acquire. Here are the first few lines of a circular Mall sent to doctors from his post at Clark University, where he worked between 1889 and 1892: “During the last few years the kindness of several physicians has enabled me to procure for study about a dozen human embryos less than six weeks old. As a specialist in embryology I ask if you can aid me in procuring more material. It is constantly coming into your hands and without your aid it is practically impossible to further the study of human embryology.” Mall was an intelligent man and an independent thinker, although painfully shy. His ideas about how to professionalize and elevate the teaching of anatomy won recognition in 1893 when he was appointed the first professor of anatomy at the new Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. For several years Mall divided his time between securing cadavers for dissection, teaching gross anatomy, collecting embryos, and promoting the fields of anatomy and human embryology. All the while, he and his colleagues in other states worked with civil authorities to set up the legislative and regulatory frameworks that would make it legal for them to acquire and dissect embryo, fetal, infant, and adult remains (Morgan 2002). After several unsuccessful bids to find funding for an embryological institute, Mall finally received a grant from the Carnegie Institution of Washington in 1913. Andrew Carnegie’s foundation had a special interest in reproductive Copyrighted Material www.sarpress.org 265 Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 266 LY N N M O R G A N science; it also sponsored eugenics research at Cold Spring Harbor and experimental marine embryology at the Woods Hole Marine Biological Laboratory (Clarke 1998; Kohler 1991). The Carnegie Institution of Washington agreed to fund a new, independent institute at the Johns Hopkins medical school to house Mall’s increasingly valuable collection, which by that time numbered more than one thousand specimens, many of them intact and unsectioned. The Carnegie Institution of Washington Department of Embryology (CIWDE) would be devoted to the systematic study of human embryology and dissemination of research results through the journal Carnegie Contributions to Embryology. Because Mall and his colleagues were bench scientists and teachers rather than clinicians, they relied on a network of clinical collaborators (many of them Johns Hopkins alumni) to provide specimens. Most of their “material,” as they called it, came from women who had aborted (whether spontaneously or by induction was not specified), although some embryos were discovered in the pathology laboratory after elective hysterectomy or at autopsy. Each new specimen to arrive would come under the care of Osborne O. Heard (1891–1983), a technician trained in sculpture and pattern making who put his skills to work on the CIWDE embryos for forty-two years, from 1914 to 1956. Heard and his assistants at CIWDE took the greatest care to photograph, fix, slice, stain, mount, and measure each specimen. Research at CIWDE centered on normal—as opposed to teratological—morphology and development, although all human embryologists were interested in the question of whether environment or heredity was to blame in the etiology of “monsters” (Mall 1908; Sabin 1934:305–307). Mall’s first two German embryos produced a steady supply of offspring in the United States. By the time Mall died in 1917, at the age of fifty-seven, the CIWDE collection had become an invaluable resource and the envy of anatomists worldwide. George L. Streeter (1873–1948), the reluctant 266 www.sarpress.org Copyrighted Material Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 267 E M B R Y O TA L E S successor to the director’s post after Mall’s untimely death, lacked Mall’s vision and determination. Nevertheless, with the “generous provision” of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, operations at CIWDE were “carried on without interruption” (Streeter 1917). Streeter expanded the embryological research conducted at CIWDE to include domestic pigs, sloths, chicks, alligators, opossums, rhesus macaques, and other animals, but human embryos remained the centerpiece of the collection (Corner 1946:126). By the time George W. Corner, an eminent anatomist, science writer, and CIWDE director from 1940 to 1955, wrote his popular book Ourselves Unborn in 1944, he could boast, “In the laboratory where these words are being written, 9,000 human embryos and fetuses have been entered in the record books, each one with its history of frustration and its challenge to new discovery, each an honored and cherished gift upon the altar of truth” (Corner 1944:28–29). The collection was considered embarrassingly old-fashioned by the 1960s, and at one point it was nearly destroyed. It got a new lease on life in the 1990s in the form of the visible embryo project, which digitalizes specimens for online viewing and sectioning (see, for example, Smith 1999; http://embryo.soad.umich.edu/). Today the renowned collection, with nearly ten thousand specimens, is housed at the Human Developmental Anatomy Center, part of the Research Collections division of the National Museum of Health and Medicine. The construction of embryology as a new area of expertise in the United States arose in tandem with rational, scientific practice and the “disciplining” of reproductive sciences (see Clarke 1998). Embryology was divided into two realms: experimental marine embryology, centered at Woods Hole, and human embryology, based at CIWDE at Johns Hopkins. CIWDE was able to transform human embryology from an anatomist’s hobby into a respectable professional specialty. Mall and his colleagues obtained Copyrighted Material www.sarpress.org 267 LY N N M O R G A N what had formerly been considered waste and turned it into prized objects. They created a new vocabulary that alienated embryological “specimens” from their origins in women’s lives. They cast alternative forms of pregnancy knowledge—such as that produced by women and midwives—as insignificant, superstitious, or wrong. They entirely ignored the women who contributed specimens; indeed, they celebrated the physicians—not the pregnant women—who gave specimens to the collection. The work they did resulted in the consolidation of embryological knowledge, as well as the embryos themselves, within a powerful and tenacious biomedical context. After their initial work setting up the research facilities and collecting networks, CIWDE embryologists and their colleagues at other institutions faced the question of how to interpret sectioned embryos. What could they read from their models and slides? What secrets would the embryos reveal? As they dissected and described the specimens, they began to ascribe meaning to their creations. Some of their descriptions were narrowly corporeal, such as the development of the aortic arches. But in the process of describing the human embryo’s empirical features, the embryologists reified and constructed the embryo, changing it from a speculative notion or putative entity into a tangible, verifiable object (Duden 1993b:2). CIWDE embryologists helped to turn what Duden called “fluxes and stagnations” (1993b:83) into modern, rational, embryo-logical knowledge. TEACHING THE EMBRYOS TO SPEAK Today’s embryos and fetuses “speak” about such a wide range of topics that it is hard to imagine them voiceless. Yet there was a time, early in the twentieth century, when embryologists pondered their mute, incipient subjects and wondered what they might have to say. Certainly the early embryos spoke about few of the topics their counterparts address today. They did not, for example, reflect on the 268 www.sarpress.org Copyrighted Material Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 269 E M B R Y O TA L E S practice of embryo collecting; that would have been impossible, because the CIWDE embryologists themselves had absolutely no reservations about collecting or sectioning human embryos. The embryologists regarded the embryo as a bit of biological material pure and simple, not as a political lightning rod, an emotion-laden corpse, or a quintessential symbol of life. Not surprisingly, the embryos’ first utterances could reflect only the concerns of those scientists who taught them to speak. Of course embryos never “speak” for themselves, nor do they “reveal” scientific secrets apart from the social context within which the embryos are produced (Clarke 1998; Haraway 1992; Hartouni 1997). Understandings of human embryos are always affected by context-specific meanings, which explains why they “read” differently in a jar of formaldehyde than in a commercial for long-distance telephone service. Yet the early human embryologists did not think they were inventing the embryos or telling them what to say. They thought of themselves not as ventriloquists or scriptwriters but as interpreters or as channelers who would give voice to the embryos’ materiality. Initially, the embryos could only mutter softly about their anatomical and morphological structure, which was fine with the embryologists. “Structure,” one embryologist said, “is the only distinctive mark of living bodies” (Minot 1906:19). To understand structure, embryologists used a microtome to section each specimen. By sectioning several specimens at sequential “stages” (i.e., gestational ages) and comparing the progression, embryologists could describe the development of specific organ systems. They wanted to know, for example, whether the lymphatics arose from the blood vessels and which bone centers were the first to ossify. Their audience was restricted to other embryologists. My concern in this essay is not with their morphological work, however, but with the processes through which they brought embryos to bear on social issues and controversies and, in turn, how those controversies came to appear to Copyrighted Material www.sarpress.org 269 Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 270 LY N N M O R G A N reside in the corporeal substance of the embryos. The examples that follow demonstrate how embryos were mobilized to address debates over the uniqueness of the human species, evolution, racial embryology, and the place of embryology in producing knowledge and creating the fetal subject. Through these examples, we begin to see the embryo becoming a touchstone, an icon, in the pressing social debates of the day. CONCEIVING THE EMBRYONIC SUBJECT Before the embryologists could begin to say what the embryo was, they had to establish what it was not. They had to establish, for example, that it was not unmentionable. Until that time it would have been crass even to mention the word “embryo” in polite company. Breaking that taboo was crucial to the embryologists’ mission, for if “embryo” could never be uttered, then the embryologists’ work would remain insignificant as well. The project to modernize embryo etiquette was taken up by a sensitive female champion of medicine, Armenouhie T. Lamson (1883– 1970). Lamson had migrated to the United States from Turkey with her parents at the age of twenty-five. Two years later she enrolled at the Johns Hopkins medical school to study medical literature and art (from 1910 to 1912). Lamson turned out to be a talented medical artist and writer. In 1916 she wrote a popular book called My Birth: The Autobiography of an Unborn Infant, which told the story of human gestational development as a collective autobiography, in the first person, from the embryo’s point of view.4 Lamson reminded readers that it was inappropriate at the time to discuss a baby yet unborn. In the following passage, her fetal narrator speaks to the reader about how the reader cannot speak about her: Yet to-day I am only a sweet but an unspeakable secret. Tomorrow my existence and my arrival will be heralded among many people. To-day good form and good manners have 270 www.sarpress.org Copyrighted Material Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 271 E M B R Y O TA L E S barred me from the conversation of all well-bred people. Tomorrow I shall be the only proper and interesting topic of their verbal intercourse. To-day only my mother takes me seriously and considers me in her actions. To-morrow I shall rule every member of her household. (Lamson 1916:134) The embryologists faced other challenges. They had to convince a skeptical public that a new life begins, biologically speaking, at conception rather than at quickening. Because they devoted their careers to studying the first eight weeks of gestational development, their professional legitimacy rested on acceptance of this claim. It may have been widely known by the middle of the nineteenth century that pregnancy began well before quickening, as Kristin Luker argues (1984:25). But knowing this in the abstract and believing it wholeheartedly were apparently still two different things. Judging by the number and the stridency of statements that appeared in textbooks and women’s magazines in the early twentieth century, many doctors apparently felt that their patients still needed to be convinced: The word quickening means coming to life, and it was formerly believed that the baby was not an independent living being until this symptom appeared. Of course, we know now that such an idea was entirely wrong. The baby has a life of its own from the moment of conception; this is not only scientifically established, but is recognized from the moral and legal view-points as well. (Meaker 1927:41) In our every-day way of speaking, fertilization means conception; it is the instant in which a living being begins its existence. There is no longer the slightest excuse for confusion regarding the period at which the life of the unborn child begins. Before the significance of fertilization was understood, it was perhaps not unreasonable to believe that life began with quickening or about the time the fetal heartsounds could be heard. But now we must acknowledge that Copyrighted Material www.sarpress.org 271 Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 272 LY N N M O R G A N both these ideas were incorrect. The animation of the ovum at the moment of conception marks the beginning of growth and development which constitutes its right to be considered as a human being. (Slemons 1917:27–28) The most effective way for embryologists to prove that pregnancy began with conception was to materialize the embryonic body, to show that it had (i.e., to give it) a shape and a form (Morgan 1999). Embryologists provided the evidence and interpretations of corporeality—in the form of drawings, serial sections, models, scientific articles, and stories—that changed the way embryos were envisioned and imagined. Prior to this time, we might say that miscarried embryos lived and died “in nature,” without passing through a cultural phase. The embryologists added a “cultural phase” to embryo existence, paradoxically, by turning dead embryos into evidence of life. Their results produced a material embryonic form upon which cultural attributes could be projected. Another challenge faced by the embryologists was to dismantle the theory of prenatal influence. Well into the twentieth century, many people, including doctors, believed that the unborn child was subject to prenatal influence (also called “maternal impressions”), defined as “the idea…that the growing child may be marked, injured or deformed in some way by the anger, fright, horror, depression or other emotional disturbance of the mother” (Reed 1924:17). Prenatal influence was blamed for birthmarks and birth defects such as cleft palate and clubfoot, behavioral idiosyncrasies, food likes and dislikes, personality characteristics, and so on. The doctrine of prenatal influence was more than idle belief; it was a prescription for behavior. Pregnant women were not supposed to overstimulate, exert, or upset themselves for fear of adversely affecting the child-to-be.5 Embryologists regarded the idea of prenatal influence as biologically impossible. They insisted that the placenta 272 www.sarpress.org Copyrighted Material Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 273 E M B R Y O TA L E S created an impermeable barrier between pregnant woman and embryo. Embryos, they said, should be regarded as autonomous entities, and women as passive albeit indispensable “incubators” rather than active participants in the production of new persons. In the following quotations, we see how the scientists worked to establish embryonic autonomy, to sever the bond that connected woman to unborn child, and to interpose the scientist as the voice of truth. Superstitious mothers must be told that the infant from the very first day of its being is an independent being. The mother only provides its temporary dwelling place and supplies the necessary nourishment. Heredity and influences of unknown origin are solely responsible for accidental birthmarks and malformations. (Lamson 1916:87–88; emphasis in original) The scientific fact is that it is impossible for the mother to mark her offspring, either intentionally or by accident. Physiologists who have worked industriously on the problem declare unanimously that there is no nervous connection between the mother and the babe. There is no means by which a nervous or emotional impulse can be communicated to the child from the mother. Nutrition and excretion are the only functions of the umbilical cord which joins the child to the mother, and even through this the blood from the mother does not pass back and forth directly. The nutritive particles and the waste are selected and separated out by the action of certain specialized cells in the placenta. It really seems as if Nature had purposely erected a barrier to protect the child in the womb from injury. After the conception occurs the mother does not influence the babe. She merely acts as a highly specialized incubator. (Reed 1924:17) Mall opposed the theory of maternal impressions and lamented the fact that some doctors still espoused it. Specimen number 246 in Mall’s collection bears this note from the doctor who donated it: Copyrighted Material www.sarpress.org 273 Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 274 LY N N M O R G A N The woman from whom this specimen was obtained is the mother of two children, the youngest about seven years of age. Since then she has had five miscarriages, all of about the same age as this specimen. No history of syphilis, but have started to give her iodine of potash, with the hope that she may give birth to a child…. It would be interesting if the great fire we had recently [the Baltimore fire of 1904] could have played any part in this trouble, as she felt well up to that time, and the fright due to the fear that the fire would burn out her neighborhood, too, kept her in a state of great excitement for about 24 hours. (quoted in Mall 1908: 244–245) Mall committed himself to correcting this error. The following passage contains an uncharacteristically self-congratulatory tone, accompanied by his unbridled disdain for misinformed and improperly educated colleagues: It may be noted here that the obstetricians and gynecologists of America as a class advocate strongly the theory of maternal impresses [sic], due largely, no doubt, to their insufficient scientific education. On the other hand, we may pride ourselves over the masterful strokes of American teratologists against this theory; the experimental teratologists have produced double monsters, spina bifida and cyclopia, under the very noses of these practitioners, but they continue their futile speculations over mere coincidences. (Mall 1908:4) Although the embryologists’ outspoken opposition to prenatal influence would ostensibly improve women’s scientific literacy, there were other issues at stake. The debate gave embryologists an unprecedented occasion to boast about their superiority over clinicians, as well as to argue that all medical students should study embryology. It would take a lot of work, Mall knew, to impose the correct embryo-logic, but the embryologists’ prestige hung in the balance. Embryologists could enhance their status and 274 www.sarpress.org Copyrighted Material E M B R Y O TA L E S influence within the reproductive sciences if they could show that pregnancy was not influenced by women’s actions, emotions, or other social influences (except in extreme circumstances such as starvation or opium or alcohol addiction). Miscarriage, for example, would have to be regarded as the result of “faulty implantation” or “germ defects” rather than the Baltimore fire. If the theory of prenatal influence could be discredited, then embryologists would be exquisitely positioned to provide the most authoritative knowledge about human development. The notion of prenatal influence faded to the status of myth just as the embryological worldview became ascendant. As this transformation was achieved, gestation and the production of children came to be regarded as biological processes largely beyond the scope of human agency.6 While the embryologists were involved in skirmishes over prenatal influence and quickening, the embryo was starting to receive its first social attributes. In My Birth, for example, the embryo emerged as an opinionated little protocitizen during an era of heightened American consternation over foreign immigration and high immigrant fertility. Lamson, herself an immigrant, was undoubtedly conscious of the eugenicist stigma against foreigners that permeated medical discourse, which might explain why she cast her embryo protagonist as a nationalist: It seems that I have to bear that name [“fetus”] until the time comes when I am born and my parents give me a permanent name. I hope that name, which I shall have to bear all through life, will be the true product of the country I am to call my “country.” It is a pity that a great country, like the one to be mine, is filled with names founded on stolen or borrowed roots from dead countries and gone people. It seems to me it is time that there should be invented names which stand for American liberty and democracy for American boys and American girls to live up to. Such a one I would wish to bear. (Lamson 1916:110) Copyrighted Material www.sarpress.org 275 Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 276 LY N N M O R G A N Lamson’s patriotic little embryo suggested that being born was like coming to America, picking (or sometimes being involuntarily granted) a new name to mark the change in residence and identity. In hindsight, we can see that the cultural work performed by embryologists was extraordinarily important. They conceived the embryo as a purely biological product, dismissed any notion of social influence over gestation, and relegated women to an ancillary, incidental role in development. They legitimated the collection and possession of human embryos, claiming them as literal possessions under the law as well as their own intellectual property (Morgan 2002). They ascribed to themselves the power to define what constituted legitimate embryological knowledge and who they would allow to generate and pursue that knowledge. This is a story about the professionalization of embryology, but it is also much more than that. Out of this scientific practice emerged a social entity that would eventually come to hold enormous power. F R O M A N I M A L TA I L S T O H U M A N TA L E S Today embryos and fetuses have moved far out of the laboratory and beyond the realm of embryology; they live in common public space, where warring constituencies battle over what they will mean. A hundred years ago, almost the opposite was taking place. To the extent that anyone took an interest in human embryos and fetuses, embryologists were moving them from the realm of women and families into the inner sanctums of science. By the time the embryos began to speak, therefore, the embryologists were the only ones around to listen. Or, to put it another way, the embryologists granted themselves the prerogative of animating the embryos and deciding what they had to say. What were those embryonic tales? A hundred years ago even the humanity of the human embryo was not yet secured. Whether because of the work then being performed by the experimentalists at Woods 276 www.sarpress.org Copyrighted Material Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 277 E M B R Y O TA L E S Hole (Werdinger 1980) or because of the associations suggested by embryo morphology, human embryos were apt to be described using piscine metaphors. Many accounts emphasized their fishlike bodies, gill slits, and tails. The Woods Hole embryologists should have been Mall’s natural allies, but they were more excited by their fish and frog experiments than by Mall’s pedestrian morphological project. In comparison with the experiments they were conducting, relatively little cachet was attached to sectioning human embryos. In 1907, for example, Mall received a letter from his friend William G. MacCallum, who wrote, “I have been trying my hand at transplanting brains, livers and such things from one frog to another—I find they stand a tremendous deal of ill usage. My frog with two brains walks backwards always, and is eccentric in many ways.” Mall slogged on, untempted by the experimentalists and never included in the inner circle at Woods Hole. He was left with the challenge of how to anthropomorphize his specimens, to distinguish them from the many other embryos competing for attention. There were at the time at least two competing theories about how the “basic unity of animals from ameba to man” (Aberle and Corner 1953:7) might manifest itself in embryological development. Ernst Haeckel (1834–1919), the German biologist and philosopher, argued that the evolution of the entire animal kingdom was recapitulated in the embryonic development of a single organism (“ontogeny follows phylogeny”). According to Haeckel’s recapitulation theory, young human embryos pass quickly through all evolutionary stages on their way to assuming the human form (see Gould 1977, 2000). Ernest von Baer (1792–1876), in contrast, had argued that “development, as a universal pattern, must proceed from the general to the specific” (Gould 2000:48). Von Baer said that the early developmental stages of embryos would be more similar among related species than the later stages. This was one of the debates that shaped the meanings attached to human Copyrighted Material www.sarpress.org 277 Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 278 LY N N M O R G A N embryos; it constituted the filter through which embryologists examined and interpreted their specimens. When the embryologists peered through their microscopes at sectioned embryos, they had on their minds questions of recapitulation and anthropomorphization (Corner 1944). Whichever theory they subscribed to, there was one point of agreement: evidence would be found by examining actual embryos and by comparing embryos from different species. The answer was in the body. The tail was one important bodily feature in the Haeckelian debate, but the tail was also arguably the characteristic that brought human embryos into public discourse. One disturbing aspect of the embryological account of development was the revelation that all human embryos, regardless of race, possess tails. Possession of a tail was evidence of animality: monkeys and donkeys had tails; humans (especially civilized humans) most certainly did not. Am I satry or man? Pray tell me who can, And settle my place in the scale; A man in ape’s shape, An anthropoid ape, Or a monkey deprived of a tail? —Punch, 1861, quoted in Corner 1944:131 How could human embryos have such an unhuman (or antihuman) characteristic as a tail? Embryonic tails challenged the notion that man was created in God’s image; indeed, Satan’s tail marked him as evil. The embryonic tail also challenged the conviction that a body should reflect the uniqueness and purity of the species. As an embodied contravention of the symbolic boundary between humans and animals, the tail was depressing news. Yet the evidence emanating from the embryologist’s laboratory could not be disputed; this was the corporeal form that science revealed. 278 www.sarpress.org Copyrighted Material Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 279 E M B R Y O TA L E S The tail would have to be explained, accommodated, and controlled. Here I mention four efforts made by embryologists and their proponents to discipline and regulate the embryonic tail. Telling Tails Lamson’s embryonic protagonist in My Birth was quite proud of her developmental progress, with one exception. She found her tail to be embarrassing and shameful. Lamson, in her three-week embryo persona, reported: “Fortunately my body—with a head and tail end—had taken such a curved attitude that the latter, painfully suggestive of my remote ancestors, was carefully hidden away from sight. It is perhaps for this reason that all undeveloped beings like me modestly retain such a position until they have received all the pleasing features of man” (Lamson 1916:60). Lamson’s narrator thought her strong bones “remarkable,” but she always mentioned her tail with chagrin: “There was in reality so little of me, and that very ungainly. In spite of my remarkable skeleton, externally I was just a fishlike being with an ugly and unproportioned head and a suggestive and offensive looking tail” (1916:67–68). And later: “Another happy incident, which had already taken place by the fourth month, was the complete disappearance of my tail—an embarrassing heritage from my remote ancestors. But at that time all of it was well buried within the tissues of that neighborhood” (Lamson 1916:109). Lamson obviously wanted embryos to speak about progressive, corporeal development, but the tail (“painful, suggestive, offensive”) presented a formidable challenge. Lamson’s embryo did what any good late-Victorian girl would do under the circumstances: she hid it modestly, buried it under other tissues, and waited for it to go away so she could stop looking like a fish and achieve the “pleasing features of man.” Copyrighted Material www.sarpress.org 279 Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 280 LY N N M O R G A N Tails of the Orient Whereas Lamson represented the embryonic tail as an impediment to individual progress and achievement, Adolph Hans Schultz (1891–1976) presented the human tail as evidence of embodied racial difference. Schultz was a Swiss physical anthropologist and primatologist who came to Baltimore from Zurich in 1916 to work in Mall’s lab measuring embryos. He published prolifically on comparisons between animal and human embryos and between white and Negro embryos, including two articles specifically about embryonic tails. In his 1925 article “Embryological Evidence of the Evolution of Man,” Schultz wrote that “man, in the embryonic state, still possesses a true external tail” (1925a:249). He mentioned, on the basis of an 1889 Scientific American account, the case of a twelveyear-old boy from French Indochina who had a nine-inchlong external tail. Schultz included a picture he had drawn from a photograph of the child, who appears nude except for the ankle bracelets that, along with his tail, mark him as doubly primitive (fig. 9.1). By drawing the comparison between the Western, civilized, embryonic tail and the fully articulated tail of a primitive Other, Schultz created two effects: he showed “us” to be more highly evolved than “them,” and he positioned scientists as the arbiters of biological and ethnological truths. De-tails Ross G. Harrison (1870–1959), also an embryologist, was not in the least tempted by ethnological comparison, because in his view the body would reveal all. Harrison spent the early years of his career at Johns Hopkins, working with the embryologists and studying nerve development by grafting tails onto frogs. He published one article about human tails, which he called “caudal appendages” (note the semantic shift from popular to scientific terminology). He began by acknowledging the widespread belief that some peoples had tails but said his review of the liter- 280 www.sarpress.org Copyrighted Material Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 281 E M B R Y O TA L E S Figure 9.1 Adolph Schultz’s drawing of an Indochinese boy with a tail, published in his 1925 article “Embryological Evidence of the Evolution of Man.” Reprinted with permission of the Washington Academy of Sciences. ature on humans did not support accounts about “various lands supposed at one time or other to have been the haunts of human races with tails” (Harrison 1901:96). Harrison retold the story, converting it from fairy tale to scientific truth. He concluded that travelers’ fanciful stories should be replaced by scientific observation; his approach was to bring the tail into the medical realm. He knew from personal experience that individual humans were occasionally born with tails. The remainder of his article described a de-tailing operation he performed Copyrighted Material www.sarpress.org 281 Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 282 LY N N M O R G A N on a six-month-old child in Baltimore, from whom he removed a seven-centimeter tail. Using meticulous anthropometric techniques, Harrison dissected, measured, and otherwise subjected (and subjugated) the tail to medicine’s objectifying gaze. He produced pages of measurements that allowed him to address an ongoing debate about whether human embryonic tails shrank in the course of development or whether they were swallowed up “as a result of the growth of the extremities and the gluteal region” (Harrison 1901:101). This arcane debate—and the embryologists’ concomitant project to medicalize the anomalous human tail—continued for many years as the embryologists “de-tailed” one embryo after another (see Kunitomo 1918). Monkey Business The most pressing and problematic evocation of embryonic tails occurred in debates over whether humans had evolved from apes. Schultz could not resist invoking the embryonic tail once the Scopes trial got under way in Dayton, Tennessee, in July 1925. He had turned down an invitation to provide scientific testimony in support of the Darwinian theory of evolution: “D. F. Malone had wired me from Dayton, inviting me to come as expert witness but I declined to participate in that circus” (Schultz 1925c). Schultz may have refused to take the stand, but he nonetheless felt obligated to take a stand. At home in his chimpanzee lab, he named the largest male chimp “Dayton.” Unlike Lamson, who found the tail an affront to modesty and humanity, Schultz seemed amused by it. He wanted to argue that humans and monkeys were descended from a common ancestor, so he used the tail metonymically to portray the human embryo as unborn monkey. With the trial in full swing, Schultz wrote a short article for Scientific Monthly called “Man’s Embryonic Tail” (Schultz 1925b), which began: “How can a self-respecting scientist claim that his and everybody else’s ancestors once 282 www.sarpress.org Copyrighted Material Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 283 E M B R Y O TA L E S possessed tails like those of monkeys? For no less a reason than that every man at an early stage in his own life-time is ornamented with such an appendage, which, to be true, serves no other purpose than that perhaps of making him feel justly proud of the fact that this organ long ago ceased to be a permanent part of his outer body” (Schultz 1925b:141). Not only did human embryos possess tails, Schultz teased, but our human ancestors once wagged them. He pointed out that human adults sport “purposeless” muscles in their rear ends that “invariably correspond to muscles found in the tails of monkeys” (Schultz 1925b:142). Schultz used the occasion of the Scopes trial to focus on the embryo tail, which would tell a story about the continuity between humans and animals rather than about human distinctiveness. As evidence of his claim, he taught the embryos to bend over and display their backsides. T R A N S N AT I O N A L A N D R A C I A L E M B RY O L O G Y The human embryologists of Mall’s day wondered whether embryos would embody racial differences the way they embodied species differences. Progressive-era doctors and other social reformers in Baltimore were concerned about the effects of immigration on medical and public health problems. The eugenics movement was becoming popular with intellectuals, politicians, and the lay public, many of whom presumed that there must be a biological basis to social and racial inequality. In this climate, some embryologists expected to find racial differences embodied in the structure of human embryos (Schultz 1925a). Racial embryology was encouraged by physical anthropologists, who were at the time busy collecting, measuring, and comparing specimens of different racial “types” (Cotkin 1992:70–71). One such anthropologist, Al?s Hrdli?ka, at the United States National Museum (later the Smithsonian Institution), regularly asked Mall—who had charge of a large anatomy lab—to assist him in building a Copyrighted Material www.sarpress.org 283 Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 284 LY N N M O R G A N collection. In November 1904, for example, Mall reportedly donated thirty-five fetal and newborn specimens—all “colored”—to Hrdli?ka, with subsequent “gifts” in 1906 and 1908 (Gindhart 1989:891). The physical anthropologists thought it likely that the CIWDE embryo collection would reveal racial differences at the earliest stage of development, and they urged Mall to compare the embryos on the basis of race. Mall was not immediately persuaded by their arguments. He was an admirer of Franz Boas, who was then lobbying against immigration restrictions and biologically deterministic ideologies. Mall considered himself an egalitarian, so he was not convinced that racial differences would necessarily be evident in embryological development. But he was too much of a positivist to draw conclusions without solid evidence, so in the 1910s he embarked on a deliberate effort to collect embryo specimens of different racial types. Mall never published any data pertaining to racial differences in embryos, but he occasionally wrote about racial differences in adults, and he permitted other researchers to use his adult anatomical specimens for their investigations. Between 1904 and 1906, for example, he allowed a young anatomist named Robert Bean to weigh and measure 150 brains from his anatomical laboratory, at Hrdli?ka’s suggestion. Bean used the measurements to support Hrdli?ka’s assertion that “racial differences exist in the Negro brain” (Bean 1906:354). Bean concluded that Negro brains were smaller than Caucasian brains, “the difference being primarily in the frontal lobe” (1906:411). Based on his assumptions about the functions of anterior and posterior parts of the brain (“association centers”), Bean concluded, “The Negro has lower mental faculties (smell, sight, handicraftsmanship, body-sense, melody) well developed, the Caucasian the higher (self-control, will power, ethical and aesthetic senses and reason)” (Bean 1906:412). Mall refuted Bean’s measurements and conclusions in 284 www.sarpress.org Copyrighted Material Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 285 E M B R Y O TA L E S print, thereby distancing himself from Hrdli?ka as well as from the project of scientific racism. Mall measured 106 brains himself. He charged that Bean had used an inaccurate measuring device “borrowed from the Smithsonian Institution” (i.e., from Hrdli?ka) and that Bean had allowed personal prejudice (which Mall called “the personal equation”) to influence his observations. To prevent this from happening to him, Mall conducted his research blind, “without…knowing the race or sex of any of the individuals from which the brains were taken” (Mall 1909:9). He concluded that “with the methods at our disposal it is impossible to detect a relative difference in the weight or size of the frontal lobe due to either race or sex, and that probably none exists” (1909:15–16). Without many more embryo specimens, especially from overseas, Mall was unwilling to conclude that differences among his specimens should be attributed to race. Other factors that might account for the morphological variation, in his view, included geography, nationality, and other unspecified “conditions.” In order to answer these questions, he would have to expand his collection. We know that by 1915 Mall had a few embryological specimens from the Philippine Islands. These may have been collected by his close friends and colleagues Lewellys Barker, Simon Flexner, and other members of the Johns Hopkins medical team sent to the Philippines in 1899 by the Rockefeller Foundation for the purpose of collecting comparative anatomical material from the colonies after the SpanishAmerican war. Barker’s description of the trip mentioned that the team brought back “a large amount of pathological material to be studied later in Baltimore,” although he did not mention embryos specifically (Barker 1942:71). We also know that by 1915 Mall counted among his collection “a few pathological specimens from China,” of which he said, “A preliminary survey of these specimens shows that they are unlike those obtained in the United States which indicates that there are special conditions in the Orient Copyrighted Material www.sarpress.org 285 Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 286 LY N N M O R G A N which we do not encounter here” (Mall 1915). Embryos sent from overseas, however, were useful only if accompanied by detailed histories. In an admonishing letter to Manila, Mall thanked a Dr. Hammach for the specimens he had sent and requested additional information: “From an anthropological standpoint we like to have our specimens identified…. I am anxious to know whether any of these specimens are white” (Mall 1914). Mall had special hope for embryological specimens from what was then called the Orient, because he knew that miscegenation had already diluted many preexisting racial distinctions in North America. In 1905 he requested an “Indian brain” from a pathologist in Canada, who replied: “By the way I am a little doubtful as to the purity of the Indian strain throughout the Dominion. About here all the Indians have suspiciously French names, and when one remembers the moral character of the old ‘Courreurs de Bois’ one is inclined to suspect the origin of these names” (Molson 1905). Nevertheless, Mall wondered whether differences would be discernable if he could find enough examples of undiluted racial types. With that in mind, he wrote a circular titled “On the Study of Racial Embryology” and sent it to doctors on Canadian Native reservations asking them to preserve specimens for him. He explained his need this way: It is now desired to collect specimens from different portions of the world in order to ascertain whether the percentage of the types of variation as well as of pathological condition are constant in widely separated regions. We are still wholly ignorant regarding these points, but in order to test them I venture to ask whether it would not be possible to obtain specimens from your country in order to aid us in this work. If differences exist they would most likely be found in specimens collected from widely separated countries occupied by different races living under very different con- 286 www.sarpress.org Copyrighted Material Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 287 E M B R Y O TA L E S ditions. We can now compare European specimens with American whites; American whites with American negroes; and those from country districts with those from cities. We should like to include in this study embryos from American Indians, for we believe that the hygienic, sociological, and racial conditions between them and European embryos are greater than between American white and American negro embryos which come from people living under similar influences. Could you not inform me whether it would be possible to secure Indian specimens from British North America? (Mall n.d.) Embryos from afar were slow to arrive, however, because missionary doctors had limited opportunities to encounter them. One doctor wrote from British Columbia that in ten years’ experience he had “seen but one case of abortion and only two of miscarriage and these at six months. These Indians are not very prompt in sending for medical attendance in case of sickness as the old women manage all such cases” (Henderson 1916). A similar letter came from Nova Scotia: “I have attended the Indians here for many years but have never met with a case of abortion” (Buckley 1916). And a physician writing from Ontario said, “The Indians seldom call a medical man for confinement or abortions and it will likely be some time before I will be able to procure specimens” (Gillie 1906). Mall would have liked to do comparative research on foreign embryos himself, but during his lifetime he was never able to amass a sufficient number of embryos to feel confident about any conclusions he might draw. By the time he died, he had not published a record of the foreign embryos he had received or any comprehensive account of the racial composition of his own extensive embryo collection. The closest estimate of the racial composition of the Carnegie specimens comes from an article by Schultz, who happily took over the job of collecting foreign and racially distinct embryos after Mall died. Schultz wrote that of 704 of the “normal” specimens in good condition he studied, Copyrighted Material www.sarpress.org 287 Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 288 LY N N M O R G A N 70 percent were white, 18 percent were Negro, and the rest were “other” (4 percent) or unidentified as to race (Schultz 1920). As Schultz set out to collect nonwhite embryos, he explained his project to a colleague working at San Juan Pueblo, New Mexico: [I am engaged in] an anthropological study of racial characteristics as found in human embryos, which has been based for the most part upon the Embryological Collection of the Carnegie Institution of Washington. This comprises over 2000 specimens, most of these being white; but there are also a considerable number of negroes and a sprinkling of representatives of other races, such as Japanese, Malayan, etc. I have found marked racial differences even in the early stages of development. At the same time the individual variability is very great, and therefore we need a much more extensive material for study before definitive and trustworthy statements on the subject of racial peculiarities can be made. Of Indian embryos we have but a few. Nevertheless an examination of the latter, which show marked differences in the proportions of the face and other parts of the body as compared with white and negro in corresponding stages of development, convinces me that a further study of Indian embryos promises the most interesting results. (Schultz 1918) Most contemporary embryologists and physical anthropologists would agree that evolutionary racism—such as Schultz’s comparison of the size of the nose in Negro and white fetuses (1920)—has long since been consigned to the dustbin of anthropological history. With the exception of antievolution creationists, some of whom are still devoted to explaining away the embryonic tail,7 most embryologists find little of interest in the embryonic tail. The significant point for our purposes is that the embryologists, like the creationists, tended to discover in embryos precisely what they were looking for. That tendency is still very much with us. 288 www.sarpress.org Copyrighted Material Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 289 E M B R Y O TA L E S DISCUSSION Today, images of embryos and fetuses speak loudly about gender and reproductive politics. A hundred years ago they spoke about the singularity or continuity of humans in relation to nonhuman animals. How do we decide what embryos signify? What tales do they tell? The examples presented here suggest that embryo meanings arise out of historically particular social anxieties and controversies. A hundred years ago, embryologists were surrounded by controversy over immigration policy, evolution, eugenics and “race betterment,” and comparative anatomy. They spoke about those issues using the embryo as their medium. Today, the repertoire with which embryos are associated has been both pruned and expanded. They speak now with expert authority about grand themes: morality, compassion, kinship, the human condition. They reserve their most trenchant commentaries for the politics of gender, reproduction, and the commodification of body parts.8 The historical contrast shows the extent to which embryos take their meanings from the scripts they are asked to read, rather than from features of the embryos per se or from an unambiguous reading of sectioned specimens. Embryos do not create social controversies; rather, social controversies create embryos. The practice of collecting human embryos—slicing them into serial sections and interpreting the results through the lens of biological science—was part of the effort to discipline, regulate, and control the embryonic form (Clarke 1998). But just as embryologists materialized the embryonic body and claimed it for science, so they felt authorized to control and shape the interpretations that would be made of it. The embryologists simultaneously denied their own authorship, claiming that the embryo was speaking for itself. Their interpretations of the embryo’s corporeal features were ostensibly based on a rational, unemotional examination of the biological evidence. Yet from today’s vantage point we can see that their readings Copyrighted Material www.sarpress.org 289 Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 290 LY N N M O R G A N were products of the times in which they lived. We can also see the lasting social consequences of the knowledge they produced. They helped to construe the human embryo as an autonomous actor, detachable (at least for heuristic purposes) from women’s bodies and motivated solely by biological forces. They helped to position the embryo as an arbiter in disputes over the moral implications of possessing particular bodily features, a practice that continues today. By allowing embryos to take sides in the culture war over evolution, the embryologists introduced them to politics while ignoring pregnant women and the social circumstances that influence whether and how nascent persons come into being. In all these ways, the embryologists breathed life into their precious specimens, animating them to tell their embryonic tales. Notes Research for this essay was funded by a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Humanities and by a faculty fellowship from Mount Holyoke College. I would like to thank Sarah Franklin and Margaret Lock for animating this essay, and I am grateful to the participants in the “Animation and Cessation” seminar for their support, collegiality, and constructive input on an earlier draft. 1. See, for example, Casper 1998; Duden 1999; Franklin 1991; Haraway 1997b; Hartouni 1993, 1997; Michaels 1999; Newman 1996; Oaks 2000; Petchesky 1987; Roth 2000; Taylor 1992, 1998. 2. American physicians crusading against abortion in the 1860–1880s did invoke the embryo as a living being, but their assertions about embryonic life were based more on commonsense speculation and imagination than on tangible evidence or knowledge about the physical characteristics of the embryo. Few of them had seen many human embryos, and virtually none conducted any systematic research in human embryology. Not until the 1890s did a few American anatomists embark on the empirical study of human embryos. 3. The most recent manifestations of the abortion debate in the United States have been waged over stem cell research and the disposition of “surplus embryos” resulting from in vitro technologies of assisted reproduction. Consequently, the term “embryo” has surfacing in the news. A Lexis-Nexis keyword search of major newspapers for the year beginning 3 February 2000 yielded 290 www.sarpress.org Copyrighted Material Rem 09 1/17/03 11:37 AM Page 291 E M B R Y O TA L E S 908 articles that mentioned the word “embryo,” 433 that mentioned “fetus,” 221 that mentioned “unborn child,” and 3 that mentioned “blastocyst.” 4. For an earlier example, see The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, by Laurence Stern, published in separate volumes between 1759 and 1767. 5. A feminist analysis would note that the theory of maternal impressions functioned to give women a justification for controlling their activities and those of the people around them. In addition, it located responsibility for good reproductive outcomes within the social arena, where people could influence those outcomes through their actions, rather than in the scientific arena, where they were removed from social reach. 6. The idea of prenatal influence is coming back into vogue, not just in physiological terms (such as the effects of gestational diabetes or fetal alcohol syndrome) but in social terms as well. Examples include the well-known work of Marie-Claire Busnel and colleagues, who show that fetuses discern music and voices (http://www.france.diplomatie.fr/label_france/ENGLISH/DOSSIER/ enfance/03.html), which has led to stories of pregnant women playing Mozart to their fetuses. Christopher Coe, a biological psychologist at the University of Wisconsin, studies psychological and environmental influences on prenatal development (http://psych.wisc.edu/faculty/bio/coe.html). 7. See the website http://www.angelfire.com/mi/dinosaurs/tailbone.html. 8. See the controversy over the fetal collections of the Institute of Child Health of the University of Liverpool. The Royal Liverpool Children’s inquiry report can be found at http://www.rlcinquiry.org.uk/. Copyrighted Material www.sarpress.org 291