RealProperty in brief.B.04.08.pmd

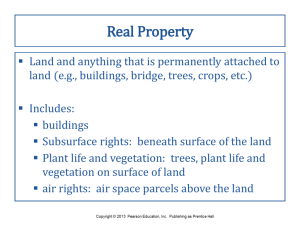

advertisement