NONTRADITIONAL STUDENTS: THE IMPACT OF ROLE STRAIN

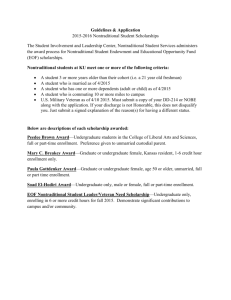

advertisement

NONTRADITIONAL STUDENTS: THE IMPACT OF ROLE STRAIN ON THEIR IDENTITY by Sherri L. Rowlands A.A.S., Business & Accounting, Mohawk Valley Community College, 1997 B.S., Workforce Education & Development, Southern Illinois University, 1998 B.S. Business & Administration, Southern Illinois University, 1998 A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science in Education Degree Department of Workforce Education and Development in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May, 2010 DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this paper to my five children: James, Brendan, Gwendolyn, Zachary, and Michael. These wonderful children may not realize it but while I was going to school as a nontraditional student and single parent, they taught me what role strain was really all about and inspired my interest in the topic. Thanks, kids! i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to gratefully acknowledge the support, help, and encouragement of the following terrific people: Dr. Marcia Anderson—Professor Emerita and Workforce Education and Development Graduate Coordinator and my advisor for this final paper. She provided tons of support, encouragement, humor, and guidance. I could not have finished it without her. Dr. Beth Freeburg—WED Interim Chair and instructor of my WED 561 – Research Methods course. She helped me get a good start on this paper. Karla Rankin—co-worker and friend who encouraged me and let me review her work for Workforce Education and Development. Brooke Thibeault—Associate Director, Foreign Language and International Trade and friend. She graciously agreed to be my outside reader for my oral defense of this paper. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION .................................................................................................................... i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... ii CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION .................................................................................... 1 Need for the Study ................................................................................................. 1 Purpose of the Study .............................................................................................. 2 Statement of the Problem ....................................................................................... 2 Research Questions ................................................................................................ 2 Definition of Terms................................................................................................ 3 CHAPTER 2—RESEARCH METHOD AND REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE ............................................................................................ 5 Overview ................................................................................................................ 5 Methods and Procedures ........................................................................................ 5 Review of Related Literature ................................................................................. 6 Nontraditional Students ............................................................................. 6 Student Identity ........................................................................................ 12 Role Strain ............................................................................................... 15 Student Supports and Accommodations .................................................. 20 CHAPTER 3—SUMMARY, CONCLUSIONS, AND RECOMMENDATIONS ......... 26 Summary of Findings ........................................................................................... 26 Conclusions .......................................................................................................... 27 Nontraditional Students ........................................................................... 27 Student Identity ........................................................................................ 27 iii Role Strain ............................................................................................... 28 Student Supports and Accommodations .................................................. 28 Recommendations ................................................................................................ 28 Recommendations for Practice ................................................................ 28 Recommendations for Further Study ....................................................... 30 Final Recommendation ............................................................................ 30 REFERENCES ................................................................................................................ 32 VITA .............................................................................................................................. 43 iv 1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Need for the Study Nontraditional or adult students are part of one of the fastest growing populations at postsecondary institutions (Fairchild, 2003). Nontraditional students are typically older and have multiple life roles. These life roles may include work and business responsibilities, parenting, spousal, and/or other familial roles, and, possibly, community and social roles and responsibilities. Entering or re-entering school adds yet another role, that of student. The student identity has been the subject of much research in traditional students but limited research has been done involving nontraditional students. The National Center for Educational Statistics identified nontraditional students as having one or more of the following characteristics: delayed enrollment in college, part-time attendance, financial independence, full-time employment, dependents other than a spouse, single parenthood, or failed to graduate from high school (Choy, 2002; Horn, 1996). These traits are also indicators of multiple roles the students must fill in addition to the student role. Adding the student role may increase the probability of role strain and affect the development of the student identity (Fairchild, 2003). Role strain has been researched as it applies to work-family roles, but the student role involves positional and relational identities in nontraditional or adult learners (Kasworm, 2005). How role strain affects the development of the student identity is a question that needs more research. An understanding of how the development of the 2 student identity is influenced by role strain may help in designing better support systems for the nontraditional student. Purpose of the Study The purpose of the study was to contribute to a better understanding of the development of student identity in nontraditional students. More specifically, the study attempted to define the influence of role conflict, role overload, and role contagion in the development of student identity in nontraditional students as an aid in designing better support systems for nontraditional students. Nontraditional students are the “fastest growing” population (Fairchild, 2003, p. 11) in higher education but the attrition rate for these students is around 32% (Allen, 1993). Support systems and accommodations for these students need to be developed by colleges and universities in order to attract and retain nontraditional students. Statement of the Problem The problem addressed in this study was: To what extent does role strain (composed of role conflict, role overload, and role contagion) affect the development of the student identity in nontraditional students, and what accommodations should be available to the students to provide the support needed to succeed? Research Questions 1. Who is the nontraditional student? 3 2. How is the development of student identity in nontraditional students affected by role strain? 3. Which variable of role strain – role conflict, role overload, or role contagion – has the greatest influence on the development of student identity in nontraditional students? 4. What supports do nontraditional students need, and what accommodations should faculty, staff, and institutions offer to eliminate or to mitigate the effects of role strain in nontraditional students? Definition of Terms Nontraditional student: Defined as having one or more of the following characteristics: delayed enrollment in college, part-time attendance, financial independence, full-time employment, dependents other than a spouse, single parenthood, or failed to obtain a high school diploma (Choy, 2002; Horn, 1996). They can be defined further as “minimally nontraditional (one characteristic), moderately nontraditional (2 or 3 characteristics), or highly nontraditional (4 or more characteristics)” (Horn, 1996, p. i). Role conflict: Defined as simultaneous, incompatible demands from two or more sources (Home, 1998). Role contagion: Defined as a preoccupation with one role while performing another (Home, 1998). Role overload: Defined as insufficient time to meet all demands (Home, 1998). 4 Role strain: Defined as a “felt difficulty in fulfilling role obligations” (Goode, 1960, p. 483). Additionally, role strain is composed of the variables of role conflict, role contagion, and role overload (Home, 1997). Student identity: Defined as a social construct within an educational setting with three primary dimensions: self-concept (the felt identity), the presented self (how one presents self to others), and the attributed self (the identity attributed to one by others) (Kaufmann & Feldman, 2004). 5 CHAPTER 2 RESEARCH METHOD AND REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE Overview The problem researched in this study was: To what extent does role strain (composed of role conflict, role overload, and role contagion) affect the development of the student identity in nontraditional students, and what accommodations should be available to the students to provide the support needed to succeed? A review of literature was conducted to answer the research questions stated. The scope of the study required research in four areas: (a) Nontraditional Students; (b) Student Identity; (c) Role Strain, and (d) Student Supports and Accommodations Available or Recommended for Nontraditional Students. Methods and Procedures The type of research used in this study was descriptive research. Best and Kahn (2006) defined descriptive research as “…concerned with conditions or relationships that exist, opinions that are held, processes that are going on, effects that are evident or trends that are developing” (p. 118). A variety of literature was available for review including research studies in several scholarly journals. Material was reviewed from those journals, government brochures, books, monographs, and several presented papers from different educational, psychological, sociological, and other organizations. Much of the material was located from several databases on the Internet. Google Scholar was used primarily in locating relevant literature. The Morris Library at Southern Illinois University 6 Carbondale has an extensive e-journal library from which many journal articles and research studies were retrieved. Key words used to locate relevant literature included “nontraditional students”, “student identity”, “role strain”, and “adult learners”. All of the literature retrieved was printed and studied extensively for information that could be used to answer the research questions. Some of the retrieved data, while interesting, did not apply to this study and was set aside. The data that did apply to this study was reviewed, analyzed, and, finally, synthesized to make conclusions and recommendations for further study. Review of Related Literature Nontraditional Students Who is the nontraditional student? Cross (1980) stated, “The term ‘nontraditional students’ is generally used to describe adult part-time learners who carry full-time adult responsibilities in addition to their study” (p. 627). In a comprehensive review of literature across the ERIC database, Kim (2002) identified three criteria researchers use to define nontraditional students. The first, and most common, was age. Students that were older than 25 years were typically classified as nontraditional (Allen, 1993; Benshoff, 1993; Bishop-Clark & Lynch, 1992; Bowl, 2001; Countryman, 2006; Darab, 2004; Donaldson & Graham, 1999; Johnson & Watson, 2004; Kasworm, 1990; Kasworm, 2003c; Kim, 2002; Richardson & King, 1998). The other two criteria identified by Kim (2002) were background characteristics and at-risk behaviors. Background characteristics included ethnicity and socioeconomic status. At-risk behaviors included part-time enrollment, full-time employment, single parenthood, or 7 high school drop-out. All of the at-risk behaviors listed by Kim were included in the list of defining characteristics used by the National Center for Education Statistics. The National Center for Education Statistics (Choy, 2002; Horn, 1996) defined the nontraditional student as a student having one or more of the following characteristics: • Delays enrollment (does not enroll directly after high school). • Attends part-time for at least part of the school year. • Works full-time (35 or more hours per week). • Financially independent for financial aid eligibility. • Has dependents other than a spouse. • Is a single parent. • Does not have a high school diploma. They can be defined further as “minimally nontraditional (one characteristic), moderately nontraditional (2 or 3 characteristics), or highly nontraditional (4 or more characteristics)” (Horn, 1996, p. i). Using these criteria, Choy (2002) reported 73% of all enrolled college students were nontraditional. Background characteristics and at-risk behaviors could be barriers to higher education (Bowl, 2001). Low income and socially disadvantaged students, single parents, and high school dropouts were highly likely to drop out of a program in the first year. Some institutions would not admit students with these characteristics (Bowl, 2001; Richardson & King, 1998: Schuetze & Slowey, 2002). Additional characteristics are described by other researchers. Some students are classified as nontraditional because English was not their first language (Tyler, 1993). 8 Fairchild (2003) reported on other common traits shared by nontraditional students, “Typically, adults are on campus only for classes or administrative requirements, as opposed to social or athletic activities (O’Connor, 1994), and they navigate college independently, without an age cohort (Benshoff and Lewis, 1992)” (p. 11). Nontraditional students attended school for various reasons. According to Benshoff (1993), these included: changing job requirements, family life transitions, changes in leisure patterns, and self-fulfillment. Additionally, Kasworm (2003c) reported some students enrolled for “education in life areas of health, religion, and citizenship” (p. 5). As a population, nontraditional students usually chose community colleges as a provider of higher education because they were more accessible (Choy, 2002; Ely, 1997: Kasworm, 2003c; Kasworm, 2003d; Kim, 2002). Kasworm (2003c) explained the choice of an institution: Adult undergraduate students typically enroll in a college that is readily accessible, relevant to current life needs, cost-effective, flexible in course scheduling, and supportive of adult lifestyle commitments. However, some adults also are committed to pursuing colleges that are prestigious (and perhaps not adult-student friendly) or that offer specialized academic programs with requirements for full-time attendance (such as architecture). Enrollment in such programs is a significant financial and life commitment for adult students. (p. 7) In other research, Kasworm (2003d) concluded, “The majority of adult students are parttimers; they do not live on campus or participate in most collegiate activities nor rarely spend time out of class with faculty and other students” (p. 5). Polson (1993) concurred 9 saying, “most [adult] students are off-campus directed” (Other Characteristics section, para. 1). Nontraditional students also had more life roles, experiences, and responsibilities than traditional college students (Cross, 1980; Ely, 1997; Fairchild, 2003; Kasworm, 2003c, 2003d; Kim, 2002). This was both detrimental and beneficial to nontraditional students. Competing life roles and responsibilities demanded time and attention and detracted from the student role. The resulting role strain affected student performance and was often a factor in student attrition (Polson, 1993; Scott, Burns, & Cooney, 1996; Tyler, 1993). Role strain was a major source of stress in adult students (Dill & Henley, 1998; Giancola, Grawitch, & Borchert, 2009; Ross, Niebling, & Heckert, 1999). Life experiences were beneficial in some cases as they helped students understand and apply some classroom knowledge. Nontraditional students were often classified as a group with poor study skills, poor time management, deficits in basic general education skills, age-related deficits in cognition, and poor academic performance (Ely, 1997; Kasworm, 1990; Richardson & King, 1998). Richardson and King (1998) stated, as a result of their research, It is clear that adult students are consistently stigmatized in terms of their capacity to benefit from higher education and that these negative stereotypes are shared by at least some educators, both as individuals and also corporately through organizations such as the APA. (p. 69) Richardson and King further maintained, These stereotypes are ageist in their content and in their implications, because they obstruct legitimate opportunities for older people to achieve 10 personal development, financial status, and political power. They are also indirectly (although somewhat less obviously) sexist, in that the majority of adult students are female. (p. 91) Richardson and King’s research was focused on disputing the negative images attributed to nontraditional students. They found, through a comprehensive review of literature related to adult students, that most of these negative stereotypes were untrue. Deficits in study skills were dismissed as “meaningless, because there is no one specific set of skills that constitutes effective studying in higher education” (p. 81). As far as time management, they concluded, “…adult students seem to make more use of timemanagement strategies than younger students” (p. 81). Age-related deficits in cognition were usually demonstrated by students age 60 or older and were “often linked with poor physical health or physical disablement” (p. 75). Richardson and King reported most nontraditional students perform academically as well or better than younger more traditional students. Other researchers agreed with this finding (Carney-Crompton & Tan, 2002; Donaldson & Graham, 1999). Donaldson and Graham (1999) stated: Despite a lack of certain types of campus involvement and recent academic experience, adult students apparently learn and grow as much or more than younger students during their undergraduate collegiate experiences. This implies that adults may be using different skills, techniques, settings, or interactions with faculty, fellow students, and others to achieve their desired results. (p. 26) Finally, deficits in basic general education were usually in math and composition and could be explained by the time away from an educational setting. Most students did 11 well in introductory courses designed to improve these skills but disliked the courses being labeled “remedial.” (Ely, 1997). Nontraditional students tended to take longer than five years to complete a degree program and were far more likely to drop out than traditional students (Horn, 1996). This was primarily due to part-time attendance but also due to breaks in education as other life roles interfered. Horn (1996) reported Nontraditional students were more than twice as likely to leave school in their first year than were traditional students (38 percent versus 16 percent). However, for students who persisted to their second year, nontraditional rates of attrition were much closer to the rates of traditional students. (p. ii) Allen (1993) reported commuting students were at higher risk for attrition and most nontraditional students are commuters. Nontraditional students had different classroom experiences than traditional students. Some researchers observed nontraditional students experienced a feeling of discomfort in the classroom and they attributed this to “a lack of self-confidence among nontraditional students about their ability to succeed” (Bishop-Clark & Lynch, 1992, p. 115; see also Kasworm, 2005). Younger students in the classroom were observed to defer to the older students and expected them to be authorities equal to the instructor. They further observed hostility between younger students and older students when the older students failed to live up to the supposed image. Faculty expectations of nontraditional students are mixed. Bishop-Clark and Lynch (1992) observed, in many classes, older students treated faculty as peers and often expected reciprocation from the 12 faculty. Some nontraditional students reported, however, they felt the faculty was uninterested in them and that the faculty would have preferred only traditional students in class. Kasworm (2005) also reported adult students complained faculty expected more from them due to their life experience and graded them a little more harshly. Student Identity How is the development of student identity in nontraditional students affected by role strain? In order to answer that research question, it was important to study the development of student identity in general. Research on identity led to one definition of identity as the “self-meanings that are formed in particular situations” (Burke & Reitzes, 1981, p. 84). The performance of a role leads to the development of the identity in that role. Burke and Reitzes (1981) noted In order to be (some identity), one must act like (some identity). In order not to be (some other identity), one must not act like (that other identity.) If being feminine, for example, means being tender and one defines oneself as being feminine, then one must act in ways that will be interpreted by oneself as well as by others as acting “tender” and not acting “tough.” In our case with the student roles and identities, if one has a student identity that is high in Academic Responsibility, then one should act in ways that have the same meaning. (pp. 90-91) Identity, then, was linked to role performance and the meanings attributed to the role by oneself and others. 13 Much of the research on the development of student identity was focused on traditional college students. A few researchers studied adult or nontraditional students (Bron, 2002; Kasworm, 2005; Shields, 1995). The research on nontraditional student identity focused, for the most part, on academic performance and motivation rather than the student identity as a whole. Student identity was defined as a social construct within an educational setting with three primary dimensions: self-concept (the felt identity), the presented self (how one presents self to others), and the attributed self (the identity attributed to one by others) (Kaufmann & Feldman, 2004). The most important dimension in mature student identity is the self-concept or the felt identity (Johnson & Watson, 2004; Kasworm, 2003a; Kasworm, 2005; Kaufmann & Feldman, 2004). The felt student identity is often based on perceptions of what a student should be or the “ideal student image” (Kasworm, 2005, p. 10). Adult or nontraditional students’ perceptions of what a student should be were colored by their age and life experiences. Through interviews with adult students, Kasworm (2005) and Johnson and Watson (2004) determined adults formulate a student identity using age-appropriate standards of behavior and life experiences. A five-stage process for developing a mature student identity was defined by Johnson and Watson (2004) and involved: • Retrospecting—looking back on past experiences to define the present • Lacking fit—being uneasy in an alien group or environment • Changing views—focusing on abilities and needs rather than deficits 14 • Student success—positive experiences foster feelings of success and accomplishment • Perceived success—being seen as successful by other students and peers. The process was influenced by beliefs about appropriate student involvement, relationships with faculty, peers, and younger students, and by the reason for going to school. Curiously, adult students who returned to school for career advancement often had weaker student identities than students who returned for other reasons (Shields, 1995). Nontraditional students formed a student identity based on participation, involvement, and acceptance in the classroom (Kasworm, 2003d; O’Donnell & Tobbell, 2007). A program designed to help nontraditional students transition to higher education was examined and discussed by O’Donnell and Tobbell (2007). They reported that the peripheral program provided limited access to services available to matriculated students and its courses in study skills, essay writing, and note taking were disdained by the students. The student identity was weak or nonexistent as students complained they did not feel like “proper students” (p. 325). Kasworm (2005) found nontraditional students formed student identities based on relationships with faculty, peers, and younger students in the classroom. Classroom involvement was based on students’ “constructed image of the ideal college student” (p. 17). Multiple role students struggled with the student identity. Van Meter and Agronow (1992) researched whether choosing the student role as the salient role would reduce role strain. They found it increased role strain unless perceptions of spousal and family support were high. Several researchers reported multiple role students dropped 15 the student role first as a coping mechanism to role strain (Adebayo, 2006; Allen, 1993; Benshoff, 1993, Berkove, 1979; Blaxter & Tight, 1994; Carney-Crompton & Tan, 2002; Clouder, 1997; Darab, 2004; Eagan, 2004; Fairchild, 2002; Feldman & Marinez-Ponz, 1995; Home, 1992, 1997, 1998; Home & Hinds, 2004; Home, Hinds, Malenfant, & Boisjoll, 1995; Scott, Burns, & Cooney, 1996; Tyler, 1993; Van Meter & Agronow, 1982). Role Strain Which variable of role strain—role conflict, role overload, or role contagion— have the greatest influence on the development of student identity in nontraditional students? Multiple identities or roles are a part of everyday existence for most people. Each role has its own demands and obligations. The student role becomes one role among many for nontraditional students and comes with a number of demands which may be difficult to fulfill and increases role strain. Adebayo (2006) commented: Students generally are faced with a number of stressors. These include continuous evaluation, pressure to earn good grades, time pressures, unclear assignments, heavy workload, uncomfortable classrooms, and relationships with family and friends (Ross, Niebling, & Heckert, 1999). In addition to these, nontraditional students are faced with employment demands and social and family responsibilities. No, doubt, combining work commitment, family responsibilities, and school obligations may be very complex and tasking. Ultimately, the struggling and juggling 16 inherent in this may create tension and health-related problems for the individuals concerned. (p. 126) Several studies have been conducted on multiple roles and role strain and most of it focused on women as subjects (Adebayo, 2006; Berkove, 1979; Carney-Crompton & Tan, 2002; Clouder, 1997; Darab, 2004; Eagan, 2004; Home, 1998, 1997, 1992; Home & Hinds, 2000; Quimby & O’Brien, 2006). This may be because women often were the primary caregivers in the home, thus they have higher demands from the family role. Researchers identified two perspectives of multiples roles and role strain—role scarcity and role expansion (Eagan, 2004). The role scarcity perspective implies multiple roles with different demands and obligations lead to role strain. Individuals did not have the strength or energy to effectively meet all those demands and, therefore, suffer from stress and other problems. To reduce role strain, decisions are made to continue or leave role relationships or to bargain with other stakeholders to meet role demands (Goode, 1960). Role expansion, on the other hand, implied additional roles are a benefit and can be a source of greater self-esteem and purpose (Eagan, 2004). Successes in one role could lessen feelings of failure or loss in another role. Multiple roles provided multiple opportunities for accomplishments and rewards. Family activities might produce more energy to cope with all other roles (Marks, 1977). One caveat to the expansion theory— multiple roles might be beneficial but they were less beneficial for women than men (Eagan, 2004). The scarcity theory was the most common view of multiple roles and role strain. In 1960, Goode defined role strain as a “felt difficulty in fulfilling role obligations” (p. 17 483). The author theorized “an individual’s total role obligations are over-demanding” (p. 485) and described five ways an individual attempts to reduce role strain which he called compartmentalization, delegation, elimination, extension, and barriers to intrusion. Compartmentalization involved setting aside other role demands to deal with a different role. This was dependent on the location and context of the role such as being a student while in the classroom. Situational urgency or crisis might also force other roles to the background. This coping mechanism could be similar to identity centrality in which group identification was used to define a role (Settles, 2004). Delegation reduced role strain by passing some role demands to someone else. Childcare, for example, could be delegated to a spouse, family member, or childcare provider. This coping mechanism was dependent having others available to take on some of the role demands. It was constrained by role demands which could not be delegated, for example, a student taking an exam. Elimination of role relationships and demands reduced role strain. If demands from a work role were causing role strain an individual might try to find a different job or student demands might cause an individual to quit school. Blaxter and Tight (1994) suggested students might use this to reduce strain: Where their responsibilities extended to two or more major roles, there were usually major doubts about their capacities to cope. They were struggling, rather than juggling, with time, and withdrawal from study or one of their other roles seemed a probable consequence. (p. 162) It was important to note some roles were not easily eliminated and other roles might involve loss of status or recognition if curtailed or terminated. 18 Extension of one role might allow an individual to plead commitments to avoid demands of another role (Goode, 1960). Expansion of a role could facilitate other role demands such as joining a club or group to increase networking possibilities. Indefinite expansion was impossible as the initial decrease in role strain was soon lost as the number of roles grew increasing role strain. Barriers to intrusion were a common coping mechanism to reduce role strain (Goode, 1960). Simple barriers such as turning off a cell phone or shutting an office door might keep role demands down. Administrators used secretaries through whom appointments must be made to control role demands. Marks (1977) did not reject or embrace the theories of role scarcity and role expansion but theorized that commitment to a role influenced whether an individual felt role strain. He suggested people have an abundance of energy and time for roles to which they are highly committed. Lesser commitment to roles with high demands could bring about role strain. Three dimensions of role strain were role conflict, role overload, and role contagion (Home, 1998). Role conflict (simultaneous, incompatible demands from two or more roles) was usually the greatest factor in role strain. In some literature, the terms “role conflict” and “role overload” were used interchangeably (Coverman, 1989). Coverman stressed role overload existed “when persons (usually women) simultaneously fulfill multiple roles, such as spouse, parent, and paid worker” (p. 967). Role contagion is described as a preoccupation with one role while fulfilling another, such as worrying about a school assignment while at work or home preparing dinner (Coverman, 1989; Home, 1998). 19 Home (1992) found that role conflict was most pronounced between student and parenting roles. This was confirmed in a later study. The perception was that family and student work “just never ends” (Home, 1998). Giancola et al., (2009), in a more recent study, found students reported the greatest stressors were school-family conflict. Low incomes, course work (rather than internships or thesis), and children under age 13 were all factors in role strain in female students (Home, 1992, 1997, 1998; Home & Hinds, 2000). The best predictor of role strain, however, was an individual’s own perceptions of role demands. Feldman and Martinez-Ponz (1995) conducted a study which examined an individual’s perceptions of role strain using the variables of self-efficacy and self-esteem. Students reported lower perceptions of role strain when perceptions of self-efficacy and self-esteem were high. Clouder (1997) found most women accept all role demands as legitimate and try to fulfill then. Darab (2004) agreed saying “the degree of difficulty is exacerbated because they [female students] continue to accept primary responsibility for family work” (Role Strain and Stress section, para. 1). Once perception of role demands was factored out, low income became the most significant variable in role strain. Time and energy spent to cover expenses on a limited budget could stress even dedicated students (Fairchild, 2003). Role strain from increased roles and their demands and from time conflicts was associated with high stress, depression, and anxiety in women students (Carney-Compton & Tan, 2002; Darab, 2004). Carney-Compton and Tan also found nontraditional students performed at a higher academic level than traditional students even though they had more stressors and fewer sources of instrumental and emotional support. High academic 20 achievement led to greater satisfaction, self-esteem, role gratification, and ego enhancement. The exception to this may be work-school conflict. Lundberg (2004) reported students working more than 30 hours a week performed less well and had lower grades on course work. Work-school conflicts were less common but when they occurred, the student role suffered and, occasionally, was eliminated. Student Supports and Accommodations What supports do nontraditional students need, and what accommodations should faculty, staff, and institutions offer to eliminate or to mitigate the effects of role strain in nontraditional students? Three areas of support have been identified as family, workplace, and educational institutions. The best support for nontraditional students was perceived support from their families (Berkove, 1979; Clouder, 1997; Home, 1992, 1997, 1998; Kirby, Biever, Martinez, & Gomez, 2003; Quimby & O’Brien, 2006; Van Meter & Agronow, 1982). Berkove (1979) identified four areas of husbandly support for adult female students – attitudinal, emotional, financial, and behavioral. Women reported less stress from husbands purporting more liberal views regarding women’s roles and abilities. Van Meter and Agronow (1982) found that Women who place the family role first were more likely to perceive their husband’s agreement with that role choice and also his emotional support for her school endeavors outside the family regardless of whether there are children present or not. . . . Furthermore, the data suggest that for the 21 woman who puts another role first, her partner’s agreement with that choice is vitally important in alleviating role strain. (p. 136) Quimby and O’Brien (2006) suggested a secure family attachment predicted well-being in female students along with parenting and student self-efficacy, self-confidence, and perceived social supports. Family support was so important some researchers recommended orientation programs and social events involving the whole family (Berkove, 1979; Carney-Crompton & Tan, 2002; Home, 1992; Kirby et al., 2003; Quimby & O’Brien, 2006). Workplace demands were less likely to cause role strain due to fixed hours and fixed tasks but paid study leave was a significant source of support to students where it was available (Home & Hinds, 2000). Other workplace supports included use of equipment and resources, job sharing, and flexible scheduling. Co-workers and superiors can provide information about workplace education polices and support students in their efforts (Home & Hinds, 2000; Home et al., 1995). Institutional supports might help with role strain but most educational institutions still had traditional student mindset. Blaxter and Tight (1994) researched how adults managed life-long education and had this to say about institutions’ perceptions of adult students: Lifelong education is clearly becoming a reality in societies like ours, but at an individual rather than a societal level. Adults are increasingly expected, and often required, to engage in serious study if they are to maintain or improve their employment positions and make the best use of their life chances. But this reality is coming about without much planning 22 and it is being achieved by placing a disproportionate element of the responsibility and burden upon the individual adults themselves. They are being expected to take on the role of student in institutions where the perception of the student role is of someone with no other major commitments, and with little or no reduction in their other responsibilities. (p. 162) Because of this perception of adult students the supports offered by institutions were rarely what the students truly needed. Ely (1997) reported Nontraditional students have made the additional following suggestions: (a) Separate registration, advising, and orientation; (b) improved access and availability to parking; (c) special assistance with financial aid and housing (easy to understand, simplified paperwork); (d) improved information services and communication networks; (e) increased social networking and support; (f) increased and convenient counseling services for adults; (g) increased availability of weekend, evening, and off-campus classes; (h) better preparation of faculty and staff to meet the needs of nontraditional students; (i) availability of childcare; and (j) credit consideration for life and work experience. Other services considered important, but are often unavailable to nontraditional students, include health services and publications for adults (Benshoff, 1993, p. 12-13). (p. 4) Countryman (2006) found nontraditional students requested more tutorials and labs, optional class offerings such as night, weekend, and afternoon courses, childcare 23 services, accessible parking, and additional campus safety. Allen (1993) suggested institutions provide more financial aid specifically for nontraditional students, flexible advisement and counseling with “well-trained staff who are alert to the special problems of nontraditional students who are at risk of dropping out of school” (Academic Advising and Counseling section, para. 1). Tyler (1993) suggested institutions and individual faculty members needed to quickly identify “at-risk” nontraditional students by having students complete an index card answering simple questions about how long they had been away from school and how many social roles they had. The answers to these questions could “red-flag” at-risk students. Accelerated degree programs are available in some areas and are designed to allow students to complete a degree program in two years or less. This involves, usually, in taking one course, or possibly two, a month on nights and/or weekends. Kasworm (2003b) reported adult students in these programs “believed that they were in a supportive world defined for adult learners” (p. 18). Students found the programs convenient, well-structured, and focused. Students had to develop a new set of learning strategies to cope with the accelerated pace of the courses. Kasworm (2003b) reported Successful adult students created a mental life space to do the course work and attend the class sessions, create a new time schedule to keep up with the pace, and rethink their other role commitments in relation to this new and important commitment to the degree program. If adult participants could not adjust to the demands of the course work and could not keep up the pace of learning through the accelerated learning classroom, they dropped out by the end of the second course. (p. 21) 24 Accelerated degree programs were available at few accredited universities at the time of the research but they seemed to be a viable choice for multiple role students looking for a supportive learning environment. Distance education, another educational choice, was becoming more wide spread and allowed students more control over when, where, and speed of learning, but in many institutions it was offered only to geographically challenged students (Carney-Crompton & Tan, 2002; Home, 1998, 1997; Home & Hinds, 2000). This option required students to be self-directed and motivated; there was a high drop-out rate and it rarely attracted low income students (Home, 1998). Another institutional support was flexible scheduling of courses and adult services. Research at a Weekend College program found the program substantially reduced the impact of returning to school on the family, work, and social life of students (Kirby et al., 2003). They noted a lower number of childcare problems possibly due to the availability of other family members, more support from families, and increased status at work. Other scheduling options, such as night courses, varied in actual support based on other life situation variables. Students who were also parents faced a unique challenge in returning to school. Whether they were single parents or had a partner, the age of the children could be a significant factor in role strain. Children younger than 13 years old required more attention and role conflicts involving school and parenting demands were common. Medved and Heider (2002) suggested faculty and staff should be aware of student-parents in the classroom. Faculty-student interactions were important for student persistence and achievement. Institutions could also offer low-cost childcare for student-parents. 25 Several other support suggestions were offered by different researchers. Financial aid was a mixed support for nontraditional students. It helped with the costs of education but, if in the form of loans, added stress about an increasing debt load. Renegotiating financial aid availability and regulations was a topic for further examination. Flexible assignment deadlines actually increased role strain in many students because uncompleted work still demanded attention (Home, 1998). Fairchild (2003) suggested educators focus on learning skills and knowledge applicable to life circumstances. Targeted orientation sessions for the student and family might be beneficial for adult students especially if they involve fellow students that had already been coping with multiple role demands. Individual and group counseling with peers, faculty, staff, and professionals could provide a valuable tool for students trying to cope with role strain (Berkove, 1979; Home, 1998; Home et al., 1995). The biggest institutional support might be, however, educator awareness of multiple role adult students. Perhaps Bron (2002) said it best: It is possible to have different identities, or several, at the same time, can cope with them accordingly in different social situations, family, work, being with friends. Because of changes in life, like in emigration or changing the career, where new culture, new language, and symbols as well as meanings are involved we can enrich and shape our lives again and again. To capture such processes is essential for understanding human conduct and becoming, but most of all, for adult educators, to capture the intersubjectivity of human learning. (p. 16) 26 CHAPTER 3 SUMMARY, CONCLUSIONS, AND RECOMMENDATIONS Summary of Findings Nontraditional students are a diverse population with many traits and characteristics that set them apart from the traditional student body at higher education institutions. They are typically more than 25 years old and often have other roles and responsibilities. These multiple roles might make it difficult to develop a strong student identity. Student identity is a felt self-concept based on perceptions of what a student should be. Adults adjust that perception by age and life experiences as they strive to fit in with the group. A weaker student identity may lead to poor performance or attrition in nontraditional students. Multiple roles can cause role strain in nontraditional students. Role conflict, overload, and contagion can impact the development of the student identify and affect student persistence and achievement. To be successful, these students may use several coping mechanisms and supports. Family provide the best support for multiple role nontraditional students. Workplace supports, where available, also help students cope with multiple roles. Institutional supports and accommodations vary in their effectiveness and, often, fail to meet student needs adequately. Several suggestions were made by various researchers on how institutions can help nontraditional students. These included family events and orientations to improve family support, flexible course and assignment scheduling, 27 flexible hours for registration and administrative duties, increased information on and availability of financial aid, and training for faculty and staff to increase awareness of nontraditional students’ needs. Conclusions Nontraditional Students Who is the nontraditional student? It was clear that a large number of students attending higher education institutions were nontraditional in the sense they were not young students just out of high school. They were usually more than 25 years old and had other various traits described by these researchers that included multiple roles, parttime attendance, and working full time among other at-risk behaviors. They usually performed as well or better than younger students but they may have taken longer to complete a degree program due to part-time attendance and breaks in education. They had a high attrition rate, and they needed various supports and accommodations to be successful. Student Identify How is the development of student identity in nontraditional students affected by role strain? Role strain did have an impact on the development of student identity. Role strain created stress and anxiety in students. If the role strain was difficult for students to handle, the student role was frequently eliminated. Students who successfully coped with role strain often had family support. The choice of the student identity as a salient role 28 helped strengthen the student identity but increased role strain when family support was not present or limited. Role Strain Which variable of role strain—role conflict, role overload, or role contagion—has the greatest influence on the development of student identity in nontraditional students? Role conflict appeared to have the greatest influence on the development of student identity. Role conflict was defined as simultaneous, incompatible demands from two or more sources. It required an either/or choice. Students had to choose which role demand to fulfill. Family demands often took precedence over the student role. Role overload and role contagion had some influence on the development of student identity but to a lesser degree than role conflict. Student Supports and Accommodations What supports do nontraditional students need, and what accommodations should faculty, staff, and institutions offer to eliminate or to mitigate the effects of role strain? Family support appeared to be the most important factor in succeeding as a student. Family events and orientations were suggested by a number of researchers as a way to bolster family support. Institutional supports such as flexible scheduling of courses, flexible hours for registration and other administrative duties, and improved financial aid were the most commonly requested by adult students. Recommendations Recommendations for Practice 29 1. Nearly three-quarters of all enrolled college students have at least one trait defining them as nontraditional, so the term “nontraditional student” needs to be dropped in favor of a more appropriate label for this body of students. Some researchers suggested using “adult students” or “adult learners” as labels for this group but in most countries, students 18 years old or older are adults, so the adult students/learners labels are not quite accurate either. Other labels suggested were “reentry students”, “returning students”, “educationally disadvantaged students”, “first generation students”, and “minority students” Perhaps the best label should be “mature” or “older students.” 2. Faculty and staff awareness of the needs of nontraditional students could be improved by training seminars and further research. Early identification of atrisk mature students is extremely important. Supportive faculty and staff can make a difference in persistence and success of nontraditional students. Some consideration should be given to alternate scheduling of assignments, exams, and presentations to help students resolve role conflict. 3. Increased resources of and information about financial aid should be a priority of any higher education institution that wants to attract and keep nontraditional students. Financial aid is extremely important to most students, but nontraditional students may have other financial responsibilities that could be impacted by the demands of going to school. 4. Institutions should consider offering low-cost childcare, counseling, social networking services to nontraditional students. All of these services could mitigate role strain. In addition, nontraditional students have requested 30 improved parking and campus safety. These things may seem trivial but they could make a difference in student retention. 5. Finally, institutions should investigate the possibilities of offering more accelerated degree programs, distance learning courses, off-campus courses, and night, evening, and weekend courses. Flexible scheduling of required courses is necessary to increase student retention. Recommendations for Further Study 1. Role strain in male students is a topic that requires further study. Most of the role strain research involves women. More men are taking the primary caregiver role so research on role strain in male nontraditional students could provide further insights into what these students require to be successful. 2. Further studies into how technology can improve or offer different, preferably low-cost, options for course delivery should be conducted. Courses on interactive CD or DVD or other technologies may provide an opportunity for nontraditional students to obtain a degree at their own pace with less stress and role strain. 3. Finally, further studies into how to improve faculty and staff awareness of nontraditional students and their needs are highly recommended. Supportive faculty and staff can improve student retention and successful degree completion in nontraditional students. Final Recommendation 31 Nontraditional students have been called the “fastest growing segments” (Fairchild, 2003, p. 11) in higher education today. Ely (1997) stated Brace yourself. Enrollment growth is predicted to “skyrocket in the next few years under the welfare reform package passed by the last Congress. When welfare recipients are required to find employment, they will turn to open-access community colleges for training”(Cuancara, 1997, p. 11). In our rapidly changing society, “global competition and rapid advances in technology” (“Not Just for Kids”, 1997, p. 16) are placing increased demands on the community colleges for quick, efficient, and up-to-date training and retraining. Many of the individuals in these programs will be today’s and tomorrow’s nontraditional students. (p. 5) Today’s institutions need to be ready for some of the best students they may ever see. 32 REFERENCES Adebayo, D. O. (2006). Workload, social support, and work-school conflict among Nigerian nontraditional students. Journal of Career Development, 33(2), 125-141. doi:10.1177/0894845306289674 Allen, B. (1993). The student in higher education: Nontraditional student retention. The Community Services Catalyst, 23(2). Retrieved from http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/ejournals/CATALYST/V23N3/allen.html. Benshoff, J. M. (1993, November). Educational opportunities, developmental challenges: Understanding nontraditional college students. Paper presented at the First Annual Conference of the Association for Adult Development and Aging, New Orleans, LA. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/0000019b/80/ 13/2e/33.pdf Berkove, G. F. (1979). Perceptions of husband support by returning women students. The Family Coordinator, 28(4), 451-457. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdfplus/583504.pdf Best, J. W., & Kahn, J. V. (2006). Research in Education (10th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon Bishop-Clark, C., & Lynch, J. (1992). The mixed-age college classroom. College Teaching, 40(3), 114. Retrieved from http://proxy.lib.siu.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=t rue&db=tfh&AN=9707062561&site=ehost-live&scope=site. 33 Blaxter, L., & Tight, M. (1994). Juggling with time: How adults manage their time for lifelong education. Studies in the Education of Adults, 26(2), 162. Retrieved from http://proxy.lib.siu.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=t rue&db=tfh&AN=9502226095&site=ehost-live&scope=site Bowl, M. (2001, June). Experiencing the barriers: Non-traditional students entering higher education. Research Papers in Education, 16(2), 141-160. doi:10.1080/02671520110037410 Bron, A. (2002, March). Construction and reconstruction of identity through biographical learning. The role of language and culture. Paper presented at “European Perspectives on Life History Research: Theory and Practice of Biographical Narratives.” European Society for Research on the Education of Adults (ESREA) Life History and Biographical Research Network Conference, 7th, Geneva, Switzerland. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/0000019b/80/ 1a/12/03.pdf Burke, P., & Reitzes, D. (1981). The link between identity and role performance. Social Psychology Quarterly, 44(2), 83-92. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/sici?origin=sfx%3Asfx&sici=01902725(1981)44%3A2%3C83%3ATLBIAR%3E2.0.CO%3B2-W Carney-Crompton, S., & Tan, J. (2002). Support systems, psychological functioning, and academic performance of nontraditional female students. Adult Education Quarterly, 52(2), 140-154 doi:10.1177/0741713602052002005 34 Choy, S. (2002). Findings from the condition of education 2002: Nontraditional undergraduates [Brochure]. U. S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, NCES 2002-012 . Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2002/2002012.pdf Clouder, L. (1997). Women’s ways of coping with continuing education. Adults Learning (England), 8(6), 146. Retrieved from http://proxy.lib.siu.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=t rue&db=tfh&AN=9705135217&site=ehost-live&scope=site Countryman, K. C. (2006). A comparison of adult learners’ academic, social, and environmental needs as perceived by adult learners and faculty. (Doctoral dissertation, Auburn University). Retrieved from http://proquest.umi.com/pqdweb?did=1147184721&sid=2&Fmt=2&clientId=150 9&RQT=309&VName=PQD Coverman, S. (1989).Role overload, role conflict, and stress: Addressing consequences of multiple role demands. Social Forces, 67(4), 965-982. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2579710 Cross, K. P. (1980, May). Our changing students and their impact on colleges: Prospects for a true learning society. The Phi Delta Kappan, 61(9), 627-630. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20385649 35 Darab, S. (2004). Time and study: Open foundation female students’ integration of study with family, work and social obligations. Unpublished manuscript, School of Social Sciences, Southern Cross University, Australia. Retrieved from http://www.pco.com.au/Foundations04/presentations%20for%20website/Sandra% 20Darab_Newcastle_paper.pdf. Dill, P. & Henley, T. (1998). Stressors of college: A comparison of traditional and nontraditional students. The Journal of Psychology, 132(1), 25-32. Retrieved from http://proxy.lib.siu.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=t rue&db=aph&AN=253723&site=ehost-live&scope=site Donaldson, J. & Graham, S. (1999). A model of college outcomes for adults. Adult Education Quarterly, 50(1), 24-40. doi:10.1177/074171369905000103 1999 Egan, S. B. (2004). Role strain in female students in graduate social work education: Culturally competent institutional responses. (Doctoral dissertation. Fordham University). Retrieved from http://proquest.umi.com/pqdweb?did=765813901&sid=1&Fmt=2&clientId=1509 &RQT=309&VName=PQD Ely, E. (1997, April). The non-traditional student. Paper presented at the American Association of Community Colleges 77th Annual Conference, Anaheim, CA. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/0000019b/80/ 14/fa/be.pdf Fairchild, E. E. (2003). Multiple roles of adult learners. New Directions for Student Services, 102, 11-16. doi:10.1002/ss.84 36 Feldman, S. & Martinez-Ponz, M. (1995, October). Multiple role conflict and graduate students’ performance. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the New England Psychological Association, 1995, Wenham, MA. Retrieved from http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/0000019 b/80/14/4e/cf.pdf Giancola, J., Grawitch, M., & Borchert, D. (2009). Dealing with the stress of college: A model for adult students. Adult Education Quarterly, 59(3), 246-263. doi: 10.1177/0741713609331479 Goode, W. J. (1960). A theory of role strain. American Sociological Review, 25(4), 483496. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/sici?origin=sfx%3Asfx&sici=00031224(1960)25%3A4%3C483%3AATORS%3E2.0.CO%3B2-4 Home, A. (1992, July). Women facing the multiple role challenge. Adult women studying social work and adult education in Canada: A study of their multiple role experiences and of supports available to them. Ottawa, Canada: Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, Ottawa (Ontario). Retrieved from http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/0000019 b/80/15/8d/e7.pdf Home, A. (1997). Learning the hard way: Role strain, stress, role demands, and support in multiple role women students. Journal of Social Work Education, 33, 335–347. Retrieved from http://proxy.lib.siu.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=t rue&db=tfh&AN=9706244122&site=ehost-live&scope=site 37 Home, A. (1998). Predicting role conflict, overload, and contagion in adult women university students with families and jobs. Adult Education Quarterly, 48(2), 8597. doi:10.1177/074171369804800204 Home, A., & Hinds, C. (2000). Life situations and institutional supports of women university students with family and job responsibilities. Unpublished manuscript, Department of Educational Studies, University of British Columbia, Vacouver, Canada. Retrieved from http://www.edst.educ.ubc.ca/aerc/2000/homea&hindscfinal.pdf Home, A., Hinds, C., Malenfant, B., & Boisjoll, D. (1995). Managing a job, a family, and studies. A guide for educational institutions and the workplace = Coordonner employ, famille, et etudes. Un guide destine’ aux institutions d’enseignement et au milieu du travail. [Brochure]. University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada. Retrieved from http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/0000019 b/80/14/01/84.pdf Horn, L. (1996). Nontraditional undergraduates: Trends in enrollment from 1986 to 1992 and persistence and attainment among 1989-1990 beginning postsecondary students (NCES 97-578). U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/0000019b/80/ 14/d7/f9.pdf 38 Johnson, G. C., & Watson, G. (2004). ‘Oh gawd, how am I going to fit into this?’: Producing (mature) first-year student identity. Language and Education, 18(6), 474-487. Retrieved from http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdf?vid=2&hid=6&sid=58f2a83f-0e3d-47cb8c1a-83ff64bbbee8%40sessionmgr10 Kasworm, C. (1990). Adult undergraduates in higher education: A review of past research perspectives. Review of Educational Research, 60(5), 345-372. DOI: 10.3102/00346543060003345 Kasworm, C. (2003a). Adult meaning making in the undergraduate classroom. Adult Education Quarterly, 53(2), 81-98. DOI: 10.1177/0741713602238905 Kasworm, C. (2003b). From the adult student’s perspective: Accelerated degree programs. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Educations, 97, 17-27. Retrieved from http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdf?vid=2&hid=6&sid=53a232ca-08be-45ccba22-2dd62e8433a4%40sessionmgr10 Kasworm, C. (2003c). Setting the stage: Adults in higher education. New Directions for Student Services, 102, 3-10. Retrieved from http://www.inpathways.net/SettingtheStage.pdf 39 Kasworm, C. (2003d, April). What is collegiate involvement for adult undergraduates? In C. Kasworm (Chair), What does research suggestion [sic] about effective college involvement of adult undergraduate students? Symposium conducted at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Chicago, IL. Retrieved from http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/0000019 b/80/1b/72/a6.pdf Kasworm, C. (2005). Adult student identity in an intergenerational community college classroom. Adult Education Quarterly, 56(1), 3-20. doi:10.1177/0741713605280148 Kaufman, P., & Feldman, K. A. (2004). Forming identities in college: A sociological approach. Research in Higher Education, 45(5), 463-496. Retrieved from http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdf?vid=2&hid=6&sid=c8d3adcf-46b7-464597a2-d8e039d816d2%40sessionmgr10 Kim, K. (2002). ERIC review: Exploring the meaning of “nontraditional” at the community college. Community College Review, 30(1), 74-89. doi:10.1177/009155210203000104 Kirby, P. G., Biever, J. L., Martinez, I., & Gomez, J. P. (2003). Nontraditional students: A qualitative study of the impact of returning to school on family, work, and social life. Unpublished manuscript, Our Lady of the Lake University, San Antonio, TX. Retrieved from http://www.nssa.us/nssajrnl/NSSJ2003%2021_1/pdf/07Kirby_Peter.pdf 40 Lundberg, C. (2004). Working and learning: The role of involvement for employed students. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 41(2), 201-215. Retrieved from http://journals.naspa.org/jsarp/vol41/iss2/art1/ Marks, S. R. (1977). Multiple roles and role strain: Some notes on human energy, time, and commitment. American Sociological Review, 4(6), 921-936. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2094577 Medved, C. E., & Heisler, J. (2002). A negotiated order exploration of critical studentfaculty interactions: Student-parents manage multiple roles. Communication Education, 51(2), 105-120. doi:10.1080/03634520216510 O’Donnell, V. L., & Tobbell, J. (2007). The transition of adult students to higher education: Legitimate peripheral participation in a community of practice? Adult Education Quarterly, 57(4), 312-328. doi:10.1177/0741713607302686 Polson, C. (1993, September). Teaching adult students. IDEA Paper No. 29. Manhattan, KS: Center for Faculty Education & Development, Kansas State University. Retrieved from http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/0000019 b/80/14/83/73.pdf Quimby, J. L., & O’Brien, K. M. (2006). Predictors of well-being among nontraditional female students with children. Journal of Counseling & Development, 84, 451460. Retrieved from http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdf?vid=2&hid=6&sid=563d70c8-492c-41439375-0c2dcc53852b%40sessionmgr10 41 Richardson, J. & King, E. (1998). Adult students in higher education: Burden or boon? The Journal of Higher Education, 69(1) 65-88. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2649182 Ross, S. E., Niebling, B. C., & Heckert, T. M. (1999, June). Sources of stress among college students. College Student Journal, 33(2), 312-317. Retrieved from http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail?vid=2&hid=6&sid=24317db0-c29d-4742bbe42ef797126ef1%40sessionmgr12&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZSZzY29wZ T1zaXRl#db=tfh&AN=1984378 Schuetze, H., & Slowey, M. (2002). Participation and exclusion: A comparative analysis of non-traditional students and lifelong learners in higher education. Higher Education, 44(1), 309-327. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3447490 Scott, C., Burns, A., & Cooney, G. (1996, March). Reasons for discontinuing study: The case of mature age female students with children. Higher Education, 31(2), 233253. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3447886 Settles, I. H. (2004). When multiple identities interfere: The role of identity centrality. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(4), 487-500. Retrieved from https://www.msu.edu/user/settles/papers/Settles%20When%20multiple%20identit ies%20interfere.pdf Shields, N. (1995). The link between student identity, attributions, and self-esteem among adult, returning students. Sociological Perspectives, 38(2), 261-272. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1389293 42 Tyler, D. (1993, May). At risk non-traditional community college students. Paper presented at the Annual International Conference of the National Institute for Staff and Organizational Development on Teaching Excellence and Conference of Administrators, 15th, Austin, TX. Retrieved from http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/0000019 b/80/13/0c/4f.pdf Van Meter, M. S. & Agronow, S. J. (1982, January). The stress of multiple roles: The case for role strain among married college women. Family Relations, 31(1), 131138. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdfplus/584211.pdf 43 VITA Graduate School Southern Illinois University Sherri L. Rowlands Date of Birth: March 4, 1957 111 E. Knauer St., Ava, Illinois 62907 PO Box 310, Ava, Illinois 62907 rowlands@siu.edu Mohawk Valley Community College Associate in Applied Science, Business & Accounting, May 1997 Southern Illinois University Carbondale Bachelor of Science, Workforce Education & Development, May 1998 Southern Illinois University Carbondale Bachelor of Science, Business & Administration, May 1998 Special Honors and Awards: Summa Cum Laude, Bachelor of Science, May 1998 Summa Cum Laude, Bachelor of Science, May 1998 Research Paper Title: Nontraditional Students: The Impact of Role Strain on Their Identities Major Professor: Marcia A. Anderson, Ph.D.