Laid-back learning

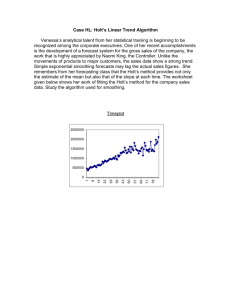

advertisement

Laid-back learning November 1, 2004 The Age ed supplement The notion of 'slow' schools is gaining ground as educators react to the pressures of timeand tests. Alice Russell reports. Cram down a hamburger. Prepared to a formula, consumed and forgot in minutes, it has passing appeal but lacks the benefits of a proper meal. In a similar way, say some parents and educators, schools are dishing up a "fast-food" education that stresses results at the expense of understanding and measures achievement with superficial tests. "We've all been influenced by this notion that quality can be measured by standardised tests and quality can be measured by ranking schools in order of their standardised test results," says Melbourne education consultant Kathy Walker. "That moves a whole community away from remembering what we're really on about, which is nurturing children so that they develop a set of skills and knowledge to help them in their life. And there isn't as much urgency as everyone seems to portray about it all happening within a given time frame." Schools have upped the pressure on children, says Fred Ackerman, president of the Victorian Primary Principals Association. Originally the prep year was, as its name implies, a preparatory class before formal learning began. No more. "There's a worldwide trend for there to be specific expectations - or what tend to be called outcomes - for all children, in all eight key learning areas, in all seven years of primary school education," Mr Ackerman says. As a consequence, young children are forced into a very structured process that "flies in the face of common sense". Some cope; some even like the routine. "But there are those children, particularly at primary school level, particularly boys, for whom those sort of expectations are placed upon them long before they're ready which can result in the opposite effect to what you would want," Mr Ackerman says. In 2002, British academic Maurice Holt, professor emeritus of education at the University of Colorado in the US, called for a worldwide "slow schools" movement. He had been inspired by the slow food movement, which started in Italy in 1986 as a protest against the arrival of McDonald's hamburgers in Rome. Its philosophy of respecting tradition and valuing culture and complexity has spread: there are now slow cities, and art critic Robert Hughes recently said we needed more slow art. Professor Holt likened schools to fast-food producers inasmuch as they were interested only in content, sequence and results that could be expressed numerically. "The pressure to proceed from one targeted standard to another as fast as possible, to absorb and demonstrate specified knowledge with conveyer-belt precision, is an irresistible fact of school life," he wrote. Two years on, Professor Holt remains convinced that we need slow schools: places that aren't geared to test results, national benchmarks or international comparisons, but that provide the intellectual space for scrutiny and argument, and where understanding matters more than coverage. From his home in Oxford he explains that slow schools place "the idea of deliberation and community at the centre of curriculum process". Parents are closely involved, teachers "have standing by virtue of their specialism and their professionalism", and schools account for their work in a variety of ways - not just by standardised tests. His call for change is chiefly driven by his conviction that standardised testing has had devastating effects on education. The tests, he says, are generally unreliable and trivial. They encourage teachers to "teach to the test", make no allowance for different communities, and lead if not to league tables at least to odious comparisons between schools. They are expensive, so only a few subjects - usually maths and English - are tested, making the remainder of the curriculum an "irrelevant sideshow". The Australian Education Union has long condemned standardised testing, which in Victoria takes the form of the AIM (achievement improvement monitor) literacy and numeracy tests done in years 3, 5 and 7. This is less than in the US and Britain but it's likely to increase: the Federal Government plans to extend it to years 6 and 10 and to science, and civics and citizenship. Some schools are already breaking ranks, and not just the alternative establishments that might be expected to step back from government guidelines. In August, as thousands of children across Victoria undertook AIM tests, life went on pretty much as usual at Spensley Street Primary School in Clifton Hill. Only 12 of the 90 eligible students did the tests. "I object to the tests because I think they are by and large meaningless," says principal Maureen Douglas. Although she emphatically does not want her school categorised as a slow one, her views on standardised testing concur with those of Professor Holt. As teachers inevitably concentrate only on what is going to be tested, she says, the curriculum tends to narrow. And the value of their professional experience is undermined. "A judgement about where a child is at needs to be made by the professionals that work with the child every day, and not by an arbitrary test," Ms Douglas says. Schools must offer the AIM tests but parents can ask for their children to be exempt. To ensure they're informed, Spensley Street runs evenings in which teachers discuss the long-term implications of standardised testing. "It puts the whole emphasis on surface skills and performance-based tasks that don't relate to deeper issues," says school council president Sarah Deasey. None of her three children has done the tests and she doesn't believe she's missed out on any enlightening information. "I feel that I know their capabilities well enough," she says. "I'm not particularly concerned about where they are in terms of the state average - what it would be showing is a fairly shallow response anyway." Avoiding the tests is only one aspect of the Spensley Street approach that recognises that children learn at different rates and in different ways. They work in mixed-age groups to encourage treatment of them as individuals, not part of an age cohort on whom similar expectations can be placed, and play is an important part of the curriculum. Play projects help them learn to stay involved with the task at hand, and encourage them to explore further, something not likely to happen if the lesson ends at the bottom of an A4 sheet. Literacy and numeracy remain high priorities, but Ms Douglas also wants students to be thoughtful, industrious, empathetic, and risk takers. "Children need a great range of activities to develop and demonstrate such skills," she says. "Why rush it? Children need time to explore and to make sense of the world, and as the children are doing that, the teachers are observing them and then using the information as a teaching point." At Collingwood College, a government prep to year 12 school, principal Frances Laurino doesn't actively discourage parents from the AIM tests, but she warns them their children will probably do poorly on the year 3 test and better on the year 5 one. For the first few years of school, Ms Laurino is happy for a "slow" approach. "As long as they're happy, as long as they're engaged, working with others, they'll learn," she says. "They mightn't learn what the education department expects them to learn, but they're learning." The school has stopped using the widespread Early Years literacy program, which requires children to spend two hours on literacy each morning and read books graded according to their difficulty. Ms Laurino became concerned when she found that children could tell her the level of the book they were reading but nothing about the content. The program's fate was probably sealed the day a small boy knocked at her door, insisted that he had to talk to her, and explained that he hated school, "because all we do is read read read and write write write. We don't do anything exciting." Soon after, Collingwood College introduced a Reggio Emilia stream, which emphasises arts and language, and responds to children's interests while covering the basic disciplines. It runs alongside a Steiner stream: among other things, Steiner educators believe that children learn when they are ready to, and shouldn't read until they're at least seven. The two "are diametrically opposite in learning philosophies but they both cater for people's need to not have their children put into a sausage machine", Ms Laurino says. But however sympathetic these schools might seem with slow school principles, they are not slow schools. And the take-up worldwide has been, well, not fast: Toronto in Canada has one, and Australia has another, the Blue Gum Community School in Canberra. Part of the problem may be the term itself: applied to food, it has pleasant connotations of simmering pots in cosy kitchens, but in education slow is not generally regarded as a desirable quality. But though Professor Holt agrees it's counter-intuitive, he wants to preserve that connection with the growing slow movement. "It's time to reclaim 'slow'," says Blue Gum executive director Maureen Hartung. "It's not about going hippie. It's that notion of having time to stop and reflect and giving students time to stop and reflect, which educational systems aren't usually very good at." Blue Gum students pass their days unregulated by bells, so that interesting studies can be pursued to a natural conclusion and lunch happens when everyone gets hungry. There are wider implications, including allowing children time to consider values and moral judgements rather than simply imposing them. Last year, a debate over which of the children were entitled to use different parts of the yard led to a discussion about refugees and asylum seekers. "It's seeing the opportunities that emerge because you make the time to listen to them," Ms Hartung says. Schools can become much more "child-centred" without compromising their standards, says Ms Walker. They can still do a broad range of testing and assessment, including class tests and portfolios of work that show the child's progress: all they avoid is the mentality of children needing to reach a certain level at a certain time. "It is important to have objectives," she says. "Teachers need to know what they're striving for and where they want their children to get to, but we don't want parents or teachers - and most of all we don't want students - thinking that they aren't quite good enough because they might not have got it in the time frame set by the government, or whoever is setting those expectations." Next year, the Victorian Government will introduce a new curriculum, known as Essential Learnings, that has some aims in common with Professor Holt's idea of slow schools. It will give generic, social and personal skills the same weight as knowledge acquisition, cut back on content to encourage deeper learning, and allow schools to cater for their local communities. "It seems to me that what they're doing in Victoria is a bit like McDonald's saying, 'Hey, we're gonna have salads!' " Professor Holt says. He objects to breaking learning into categories - when a student suddenly grasps geometry, do you attribute that to knowledge or to skills? - and he says keeping standardised testing is an "inherent contradiction" that owes more to politics than education. "The legislators think that they can have their cake and eat it. They love the idea of the tests because it makes them look as though they're doing something - and if the test results are poor, they don't get the blame. They can simply kick the schools and the teachers." His slow school campaign continues. It's bound to be a long haul, he says, but interest is spreading: the American Educational Research Association meets next April for a symposium titled The Case for the Slow School. And just as we can apply "cool" to something that's hot, Professor Holt hopes we may one day see "slow" as high praise for education. WHEN SCHOOL IS BORING Soon after he started prep, Thomas' behaviour deteriorated. Ten days into his first term, he announced that school was boring. Before much longer, his mother was resorting to ice-cream bribery and became increasingly convinced her son was not ready for what his school was providing. "Within a week of starting, they were already tracing out the letter A," Samantha Rennie says. "There was not much of a play program at all." Most of the children settled into the routine but Thomas - who has just turned six took to clowning around to cover up his sense of inadequacy. "The school's response to it was that he will adapt, he will make all the changes," Ms Rennie says. Instead, Thomas moved to the Reggio Emilia stream at Collingwood College. Ms Rennie describes the program as child-inspired rather than teacher-inspired. She likes the way the development of maths and writing skills is tied to the children's interests and is happy to see that Thomas is relieved of the pressure to be at a certain stage by a certain time. His behaviour has improved and bribing with ice-cream has become a thing of the past. "He's only just now getting ready to learn to read and write," Ms Rennie says. "I know that in another year he will be ready." Although she won't stop Thomas sitting for AIM tests when the time comes, Ms Rennie is concerned about the effect that they and such programs as Early Years literacy have on schools. "Their emphasis is still about getting kids to get good scores at the end of it all," she says. "It's putting so much emphasis on the school being just about the child's intellect." MARCHING TO A DIFFERENT BEAT Susan Pardy decided she needed to do something about her 11-year-old son, James when, towards the end of year 4, the boy who had always liked learning became unhappy about going to school. "The problem for my son is that he had ceased to be engaged in his learning because he was so anxious about the fact that he couldn't read," Mrs Pardy says. "It's not that James couldn't read and it's not that he couldn't write, it's just that he didn't do it to the level of expectation and so he was losing confidence." Although James had been doing well in other areas - Mrs Pardy describes him as "a bit of a global thinker" - he wilted under the pressure of the Early Years literacy program. "The one thing that wasn't his strength was the thing that the school was requiring for the first two hours of every school day," she says. After some research, Mrs Pardy moved James to Preshil, an alternative school with a philosophy that children should be allowed to develop at their own speed. Her son's reading has improved, helped by more individual attention, he is happier and has regained his interest in learning. "Now he's back there learning about life," Mrs Pardy says. "Whereas he got to the stage at the end of last year that he was just too miserable to learn about anything." All he needed, she says, was time. "I think kids' brains develop at different rates and the education bureaucrats don't seem to recognise that. There just wasn't enough time for James to slow down and go at his own pace."