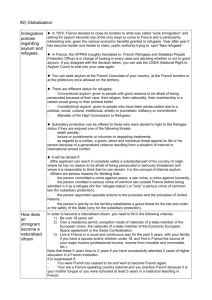

The protection of refugees and their right to seek asylum in the

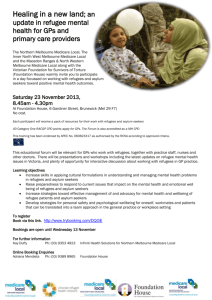

advertisement