Curved Lines: Forrest-Thomson, Klee, & the Smile

advertisement

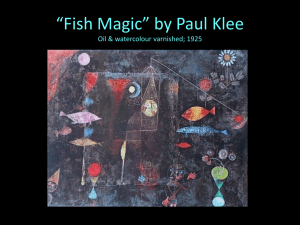

Sara Crangle Curved Lines: Forrest-Thomson, Klee, & the Smile Although integral to most paintings, contours merit special attention in Veronica Forrest-Thomson’s poem dedicated to Cézanne, presumably because the artist in question was such a keen proponent of the heavily-demarcated outline. Initially, Forrest-Thomson appears to imitate Cézanne in proclaiming “the joy of everything with edges.” Restraint, compression, and “assumed balance” are extolled as the products of the contour in the octave of this Italian sonnet, and we await the turn. It comes. The sestet reads as follows: But these tight contours owe shape and definition to the eye of inessential man who from complication learns to simplify, fuse form with what alone forms cannot show, and in this act becomes as sure as they. (27)1 Beware “tight contours”: in delineating, they delude us into a state of certainty, making us believe in what cannot be seen — “learning to simplify” is surely suspect. Forrest-Thomson is not genuinely interested in straightforward lines of clarification, and her address to deceptively clear painted lines is both satirical and readily extended to the poetic line. As she stated at a 1975 reading, the most important principle of poetry is that it “progress by deliberately trying to defeat the expectations of its readers or hearers, especially the expectation that they will be able to extract meaning from a poem” (169). Forrest-Thomson strives to destabilise her audience, a motivation clearly in keeping with the inherent unsteadiness of the phrase “assumed balance” in “Contours — Homage to Cézanne.” Pursuing the defeat of audience expectation has a much longer history than Forrest-Thomson’s twentieth-century aesthetics, albeit in the context of producing and comprehending comedy. Kant is credited as the first to define laughter as a reaction to expectations that yield nothing, an instinctual response to a mental void that emerges in place of a predicted perception. Laughter, Schopenhauer went on to argue, begins with observed incongruity; in turn, physical and societal imbalance are central to Henri Bergson’s seminal 1884 lecture on the comic. For Bergson, it is when the human body becomes rigid, mechanical, or clumsy that laughter erupts. He counters this stiffness with his own philosophical emphasis on the unrepeatable flux and flow of subjective experience, suggesting that society laughs at rigidity as a corrective, a means of ensuring “the greatest possible degree of elasticity and sociability” from its members (11). Bergsonian laughter affirms a living “comic spirit” in large part because Bergson lived in an age where it was still acceptable to use phrases such as “comic spirit.” Vestiges of this sort of language linger on today, where theorists have a tendency to describe laughter as transcendental, as if it emerges from, or can transport us to, an inexplicable metaphysical cosmos.2 Whilst her poetry exhibits a self-conscious wittiness and extols the unknown, these are not the sort of language games ForrestThomson is willing to play; as a speaker tells us in an early poem: “the individual ego (once called a soul) / must learn to let the transcendental go” (32). And while she often describes or discusses laughter in her poetry, Forrest-Thomson’s risibility does not, like Bergson’s, counter human inflexibility by affirming the flux of life. Instead, curiously, Forrest-Thomson frequently renders the act of laughing in the same way that Bergson describes the cause of laughter. Forrest-Thomson’s laughter is not directed at rigidity, but is rigid; her laughter does not free, but constrains. As one speaker tells us: “So again laughter muscles / go through their contractions nicely, for it’s [sic] all right; / you can move now” (110). Forrest-Thomson’s laughter is bitter: it emerges ironically after love is proclaimed, or is tied to the fear of becoming a laughingstock.3 “Mirth,” one speaker asserts, “cannot move a soul in agony” — in Forrest-Thomson’s poems, mirth does not even move the laugher (135). These sardonic tendencies are perhaps surprising in the work of a writer so keenly interested in the failure of language to communicate; in her extensive explorations of non-verbal expression, laughter might well feature positively as well as derisively. But while Forrest-Thomson’s levity rarely rises, her combined interests in gesture and picture produce a notable attentiveness to the curved line. And while curvaciousness takes on many guises in Forrest-Thomson’s work, it is the deflected and expressive line that is the human smile that particularly intrigues and amuses. Of course, smiling is not limited to an expression of observed humour; smiles signal joy, scorn, grimacing, and tired acceptance, among other things. But it is the very multivalence of the smile to which ForrestThomson returns; unlike her mentions of laughter, her smiles are presented complexly and playfully. In making this distinction between laughter and smiling, Forrest-Thomson is in league with traditional theories of laughter. For just as laughter has been rather singularly limited to an outcome of perceived incongruity and imbalance in philosophical thought, so too is its presentation constrained and unyielding in Forrest-Thomson’s poetry; by stark contrast, the smile emerges as a locus of open-ended interpretation and balance. In depicting the smile as a source of witty equilibrium, Forrest-Thomson echoes not philosophical thinking, but rather, considerations of the curved line in modernist aesthetics, and particularly those of Paul Klee, whose ingeniously childlike paintings directly inspired some of her poetry. To begin: some general thinking about curves. A very familiar curved line is, of course, the bracket; the word “curve” has been used as a synonym for parentheses, or curves that enclose writing too distinct for commas, and not emphatic enough for dashes.4 In geometry, a curved line is conceptualised as the tracing of a moving point, one that continuously changes and deviates from a straight line. In physics, a curve is a graph or line that represents a continuous variation of quantity. In geometry and physics, then, curves are associated with movement, change, and variety. This instability is emphasised by Mondrian, who considered curves “too emotional . . . and banished them from his art.” Critic Leo Steinberg comments on Mondrian’s rejection of the curve as follows: Consider now what manner of judgment this is — that curves are emotional. Mondrian could not have arrived at it from a consideration of their essence a priori; the proposition had to be empirical, generalised from the emotional effect which certain curves of his acquaintance had on him. Curves were weighed in their typical contexts and found guilty by association. Now suppose we apply an equally empirical test to straight lines; our enquiry will lead to the following findings: that a straight edge on a wooden surface indicates lumber, or furniture, but never a tree; that a straight line limiting a flow of water defines an embankment or canal, never a river; that a batch of fish surfacing in a flat plane betrays, not a fresh haul, but a new-opened can of sardines. A straight line, then, is the mark of human purpose, human cunning, enterprise, success. And it is a fine example of unconscious human self-congratulation that the word ‘straight,’ in our language, takes on connotations of superior virtue. (277) Steinberg’s is, perhaps, an almost too-obvious association between rectilinearity and rectitude, one that reduces Mondrian’s art to the basic — even base — aims and principles of consumer capitalism. But of course, the straight line is the pre-eminent symbol of progress. In his memoirs, artist Hans Richter suggests that in revolting against bourgeois European society, the Dadas explicitly worked against any sort of “straight-line thinking” (58). And Richter is far from the only Dada to proclaim the value of curvaciousness; on June 20th 1917, Hugo Ball wrote in his diary: “The modern artist will quite consistently avoid incorporating the impulse of his aesthetic creation into certified experience. He will convey only the vibration, the curve, the result, and be silent about the cause” (Flight 119). Similarly, in an essay on Kandinsky, Ball praises that artist’s ability to reject mimesis, “and go back to the true form, the sound of a thing, its essence, its essential curve” (Flight 226). Belief that curves are distilled essence and inspiration arises also in the writing of Jean Arp, who claimed that many of his artworks began with his perception of “a curve or a contrast that moves me” (243). Full of breasts, buds, and bowls, Arp’s sculptural oeuvre is devoted to the curve, which appeals because it is a natural, organic shape that counters the precise angularity of human constructs such as architecture. The curve, as André Breton asserts in “The Automatic Message,” reminds us of “a budding fern, an ammonite, or the curl of an embryo” (23). But more than these natural associations, the curve also evokes the infinite: it is synecdochical for the endlessness of the sphere. I’ve made much here of Dada references to the curve in large part because Forrest-Thomson holds this modernist movement in such high esteem; she dedicates a significant portion of her treatise, Poetic Artifice, to a discussion of Dada aesthetics. Forrest-Thomson is drawn to Dada because she believes that Dada writers prevent “bad naturalisations,” or readings of poems that are tied too closely to the specific meaning of words, and fail to take into account nonsemantic levels of meaning such as sound, rhythm, and cadence. For Forrest-Thomson, Dadas foreground the fundamental artifice, or unrealism, of poetic language, and, as a direct consequence of this emphasis, are adept at defeating audience expectation that art should have a discernible meaning. While recognising that this defeat of expectation can generate humour, Forrest-Thomson tells us rather sternly in Poetic Artifice that Dada writing should not be reduced to the comic. Instead, we should use our disappointment as a tool that makes us “better fitted to appreciate Artifice as readers of poetry” (PA 131) — she thus shares with Bergson a sense that humour has an ethical, improving aim. While failing to acknowledge the culturally transformative value of Dada humour, Forrest-Thomson is nevertheless attuned to the movement in other regards. As in Dada manifestos, Forrest-Thomson points out that Dada writing is nonsense but is not nonsensical; its obscurity is programmatic, as there is always discernible form behind the chaos.5 Dadas may deal in extreme unrealism, but they turn that artifice into a principle of composition — their work is not random. As such, Forrest-Thomson believes the Dadas exemplify her maxim: “A line must be struck between too much and too little experimentation” (PA 81). This boundary drawn between various degrees of experiment extends Forrest-Thomson’s abiding interest in contours and lines, and a similar urge to delineate can be located throughout her critical writings. Echoing formalist practice, Forrest-Thomson condemns criticism that moves beyond the frontier of the poem. And in “Dada, Unrealism and Contemporary Poetry,” Forrest-Thomson’s distinction between realism and “unrealism” involves a boundary both abstract and emphatically concrete. She writes: If Realism in literature aims to mediate the contours of a reality we know from non-literary experience and if it builds its linguistic techniques accordingly, then Unrealism aims to mediate the already mediate techniques of Realism into the contours of fantasy. Unrealism accepts that poets tell lies, and explores and articulates the lies with all the joy of the parodist who may step down from the telescope of theoretical despair to the microscope of technical detail. (78) The contour Forrest-Thomson describes emerges from a fantasy built out of a so-called reality. This edge lacks palpable definition, yet Forrest-Thomson insists on its sharpness, its appealing microscopic detail. Later in this same article, Forrest-Thomson suggests that in reading and writing poetry we pass through levels of meaning and their non-verbal extensions; we then return to the poetic medium with a heightened, fuller sense of its formal principles. What Forrest-Thomson describes is a roundabout journey in which we do not return to our starting point, but to a point of greater comprehension. She delineates, then, an aesthetic based on emphatic lineation, attention to detail, and curved thinking very much akin to that of Paul Klee. For instance, Forrest-Thomson’s emphasis on the minutely attentive contour recalls Klee’s painterly style: Klee is considered the master of the hair-line, and Hugo Ball admired how, “[i]n an age of the colossal” Klee could “fal[l] in love with a green leaf, a little star, a butterfly wing” (Motherwell 54). Klee painted abstractly and microscopically. But more than this, Forrest-Thomson’s travels through poetry recall how Klee, in a well-known passage from his essay “Creative Credo” (1920), takes a metaphorical line on a detailed walk. Klee’s promenades are not linear jaunts from A to B; he does not arrive at a clear destination, and does not want to. Instead, like Forrest-Thomson, Klee invites his reader to “take a little journey to the land of better understanding,” a journey that is entirely circuitous and curvaceous. I quote now from its outset: The first act of movement (line) takes us far beyond the dead point. After a short while we stop to get our breath (interrupted line or, if we stop several times, an articulated line). And now a glance back to see how far we have come (counter-movement). We consider the road in this direction and in that (bundles of lines). A river is in the way, we use a boat (wavy motion). Farther upstream we should have found a bridge (series of arches). On the other side we meet a man of like mind, who also wants to go where better understanding is to be found. At first we are so delighted that we agree (convergence), but little by little differences arise (two separate lines are drawn). A certain agitation on both sides (expression, dynamics, and psyche of the line). (76)6 As Klee’s metaphorical journey continues, it involves getting lost, and numerous encounters, including one with “a child with the merriest curls (spiral movement).” In the end, he returns us to our starting point, reflecting on our memories and impressions. Although we’re directed toward a land of better understanding, we never seem to arrive — instead, understanding emerges in the endeavour to understand, rather than an end-point reached by cunning or enterprise. Points are dead in this passage; elsewhere Klee describes the point as “an infinitely small planar element, an agent carrying out zero motion” (105). The point is an impetus, but motion is the goal, and circuitous motion in particular. The circuitousness of Klee’s journey is echoed by the curved lines he encounters: the wavy rivers, arches, the spiralled hair, even, perhaps, by the number of brackets he uses throughout. Klee’s aesthetics are inherently witty, and his brand of wit shares allegiances with Bergson, whose philosophy informed Klee’s highmodernist era and whose work on laughter remains central to humour theory. In their writings, Klee and Bergson emphasise motion and feeling; both thinkers seek a balance between dynamism and rigidity. Klee argues that life is defined by a continual oscillation between tension and elasticity; similarly, Bergson contends that the fluidity of experience is regularly countered by an inevitable, ridiculous inflexibility. In order to illustrate the connection between these extremes, Klee sketches a pendulum, arguing that it represents “a compromise between movement and countermovement, the symbol of mediation between gravity and momentum” (387). Gravity, or seriousness, is thus often contrasted by levity, or a “movement that demands expression” (389). The line Klee draws to illustrate the swinging movement of the pendulum is a concave arc, or the expression that is the human smile. For Klee, the curve and the circle are “the epitome of the dynamic,” whilst the straight line indicates “the static” (40). Elsewhere, Klee suggests that curved lines can supersede straight: “where the power of the line ends, the contour, the limit of the plane form, arises” (64).7 As in the pendulum diagram, Klee’s rising contour recalls a straight mouth curving into a smile. As for the Dadas, Klee’s interest in the curve stems in part from his opposition to his rectilinear, technologically-driven age — he finds in curves the playfulness that his art embraces. Klee’s celebration of childish humour bears similarities to Bergson’s pre-Freudian conceptualisation of the relationship childhood memory and adult laughter. But a still more specific kinship lies in Bergson’s use of the curve to illustrate levity. Bergson tells us that the curve is comical, even when it shouldn’t be, as when we mock the hunchback, or the person with an overlong nose or exceptionally large ears. Bergson uses these specific examples because, as he suggests, these curvaceous, physical “deformities” echo the comedy and appeal of the human smile; in the hunchback, he suggests, “[y]ou will have before you a man bent on cultivating a certain rigid attitude whose body, if one may use the expression, is one vast grin” (13). So far does Bergson extend this metaphor that he likens immorality to a curvature of the soul — even the spirit can express pleasure, amusement or disdain via the smile. Bergson’s discussion of the curve, then, is as widely and diversely applied as Klee’s own; the open-endedness of the expressive smile appeals to their shared emphasis on fluctuation and process over linearity and end points. As Klee writes: “In production it is the way that is important; development counts for more than does completion” (35). The curve, then, embodies infinite process, and a balanced but dynamic oscillation between extremes; by ready extension, the human smile is a multivalent gesture, occasionally tending to ambiguity. This open-endedness, of course, is part of the appeal of the curvaceous, and in Forrest-Thomson’s poetry, there is some evidence that she aims to makes broad use of the curve in a way that echoes the modernist theorists and artists she admired. In the early poem “Christmas Morning,” for instance, “A gull curved like a boomerang / slants the sky, tilting / the horizon with a surge of snow” — here, a drawn curve challenges the stability of a world perceived and presumed. The gull’s curve is paralleled by “Trees stand[ing] shrunk” as if cowering beneath “crouching clouds”; still more hunching can be located in the houses within view, which Forrest-Thomson likens to “a huddle of grey tents” (23). The view in “Christmas Morning” is etched out by curves that signify uncertainty and unresolved waiting: the speaker tells us that there is no longer anything to worship on this once-holy day, but that time must pass regardless. Lacking surety, these scenic curves foreshadow a later reference Forrest-Thomson makes to the “uncertain curves and camber” of the mythic route traversed by all readers and writers (116). Similarly unstable, dynamic curves occur in “Antiquities,” where Forrest-Thomson’s speaker declares: “A gesture is adjective, / two hands” and “Emotion is a parenthesis” (85). A meandering exploration of cultural treasures from statues in the Louvre to the Cambridge townscape, the poem insists on the relationship between the body and the body rendered; the phrase “two hands” and parentheses are repeated throughout like a quiet refrain of paired and pairable curves. As the speaker takes these small curved lines for a walk, he or she doubts our ability to contain culture in museums, art, and books, and by extension, questions our capacity to relay human feeling. In their failure to contain, gestures and brackets prove emphatically mortal indicators of the self; regardless of their efficacy, both are nonverbal forms of communication that seep into the realm of language. As in Forrest-Thomson’s poem about Cézanne, even the clearest of contours — of letters, of typography — must be treated with an appropriate degree of scepticism. And it is on this highly sceptical note that the poem ends: “The art of English Poesie? / ‘Such synne is called yronye.’” (86).8 Here Forrest-Thomson quotes The Ordynarye of Crystyanyte or Crysten Men (1502), in which the author likens false humility in prayer to the grammatical term for saying one thing and meaning another. This book contains one of the earliest written usages of “irony,” and by referring to it, ForrestThomson calls attention to a long history of self-conscious linguistic slipperiness. Lacking confidence in the capacity of language to be straightforward, the poem focuses instead on curved lines and gestures, including, at its end, an implicit mention of raising one’s hands in prayer. These gestures do not yield certain truth, but rather, an endlessly circuitous journey. Not all of Forrest-Thomson’s curved lines are quite so infinite in interpretation — many end abruptly in references to death or stasis. Forrest-Thomson’s “Subatomic Symphony” is another poem that likens the curve to the living body. Here Forrest-Thomson compares the liveliness of a wavy line to music. Music flows and ripples, while discord and twang are modulated by “[s]ounds pitched at a lower key” that “regain stability.” Like Bergson and Klee, ForrestThomson illustrates sound waves or curves oscillating from one extreme to another, yielding balance. This balance is also life generating, cyclical: tune resolves material notes of mass and energy underneath spreading like ripples of breath. (31) But as part of this curving, circular musical journey, “Subatomic Symphony” includes the lines: “Rhythm sways / to the throb of decay” — sound waves signal both life and death (30). Mortality and curved lines are twinned also in “Point of View at Noon,” where the speaker regards lime trees “fixing their contours in a mould of light” — mould suggesting both an external form and rot (19). A picture of these trees is outlined, likened to a Byzantine “ikon,” and rendered as dead as the scene immediately before the speaker. The poem reads: Framed in an unblinking eye the scene seems no more living or capable of movement than the turquoise tendrils traced on this quiet vase which holds severed roses red against the blue enamelled sky. Emphasis is placed on the deadness of cut flowers in this stillest of still lives. Yet another poem suggests that contours dissolve the future, an assertion followed by a graveyard scene.9 Cézanne’s “joy of everything with edges” is certainly dashed in these far-too-mortal instances. This association of mortality and the curve is extended to Forrest-Thomson’s poem “Ambassador of Autumn (By Paul Klee).” Also known as “Harbinger of Autumn,” the painting in question is dominated by black, bluish-green, blue, and white blocks laid out in brick-like layers that emphasise the gradations of their shading. These blocks frame two images. The first image is a tree, comprised of a black trunk and a bright orange circle, located slightly high and right of centre. Second, left and low of centre, is a white semi-circle, or half-moon shape. Forrest-Thomson’s poem plays with the shading that the picture exhibits, opening as follows: Year’s spectrum modulates around the centre spectre. Each single moment’s tone appears alone, yet signals the gradation in the air towards the centre spectre; clears a half-uncovered curve cold moon, negative reflector of the centre spectre (25) The centre spectre here presumably relates to the absent centre of the picture, as Klee’s tree and moon are deliberately offset from a figurative centre defined only by spectrums of colour. The word “spectrum,” which arises in the first line, refers to a figure that haunts, and patterned wavelengths (or curves) of light, colour, or other forms of electromagnetic radiation. In the phrase “year’s spectrum” Forrest-Thomson extends light and colour — Klee’s painterly mediums — to the temporal range of lived time: both move toward a mere spectre of the stability centeredness might otherwise portend. A sense of pointlessness is compounded by the “half-uncovered curve” of the moon: the adjectival phrase “halfuncovered” is superfluous, as a curve remains a curve, no matter how much of it is on display. But as the poem continues, even whole spheres do not fare well: the moon is considered “frail parody of sun,” and the leaves on Klee’s childishly circular tree are “about to snap, / fulfilled as things only may / whose sole future is decay” (25). While the curved moon and bright, round tree quite evidently counter the near-monochrome angularity of the layered blocks around them, Forrest-Thomson consigns both to a future of autumnal rot without spring’s rejuvenation. Once again, potentially joyous curves intimate stasis. Forrest-Thomson reads Klee’s painting one-sidedly, generating an imbalance in her poem; although replete with double meanings and word play, the poem is neither comic nor open-ended.10 With entirely different and more successful intent, Forrest-Thomson elsewhere depicts curves as dynamic, infinite counters to the linear progress toward death, and the smile best effects this affirming countering. Quite unlike “Ambassadors of Autumn,” the spectres in her elegy for Ezra Pound, for instance, do not horrify, but are easily overcome: . . . .Pluck the petal in the orchard where the factions act on emblematic colours, red and white; leap with Nijinsky always poised for entrance in La Spectre de la Rose. This spectred isle, defying death with gesture. Awhile to porpoise pause and smile and leap into the past. (132) Here image, art, and gesture can defeat time; the poem celebrates brash smiles and buoyant, curved leaps of self and faith. In like spirit, the speaker tells us repeatedly that Pound lives on, ending: “He is not dead. Instead. / Give back my swing. O Ferris wheel” (133). Like the curved smile, the swing and Ferris wheel speak to an arcing triumph and an affirmation of life’s playful cycles. With considerably less aplomb, the smile nevertheless affirms the self also in “Tooth,” where Forrest-Thomson’s speaker anticipates the dentist with trepidation, and closes with the anxious lines: “And how can I be sure / of reconstructing the framework of that smile / I left behind me at the door” (58). Lastly, Forrest-Thomson privileges curves over straight lines in “The White Magician,” where Leonardo Da Vinci is derided for presenting “the desperate flatness / of her smile” (39). A smile without a curve — however famous — is just hopeless. These examples bring us to Forrest-Thomson’s liveliest discussion of the smiling face, “Clown (by Paul Klee),” where curves idle, sidle, swerve, insinuate and grin — here the smile is a truly multivalent curve. The poem reads as follows: Clown (by Paul Klee) Seen in the wink, a link (with) green flaunt, too clear in face (of) shadows which do not appear; a jaunty impulse, yet boxed, looped (also) in a curve idling, a sidle into an angle, stencilled by heat; hot thought read through red through red thought what not? a whatnot leer clear in nose swerve, in blue insinuate grin let in seen within (is) a view somewhat askew; and you? (21) To use Forrest-Thomson’s critical language, a “good naturalisation” of this poem might entail a reading of its repetitions — seen in, insinuate, seen within. A good naturalisation might relate the winking, flaunt-y, jaunty words of this poem to its playful rhyme scheme and clownish title. Instead, I’m going to offer a bad naturalisation of this poem, in large part because I think the title asks for it. My bad naturalisation reduces the poem to what I think it means, which is as follows: Forrest-Thomson’s poem is about Klee’s 1929 painting “Clown.” The poem relies upon the painting to discuss perception, and to argue against the certainty of any single viewpoint. The speaker is playfully and adamantly opposed to straightforwardness, and enjoys oscillating between the comic and the tragic. As in Klee’s illustration of the pendulum, the pursuit of balance in ForrestThomson’s poem hinges on the visualisation of the curved shape and open-ended, expressive gesture of the human smile. First: perception. In the painting itself, a green circle on the clown’s shoulder mirrors the red, open eyeball of the portrait; the mirroring here underscores, of course, how red and green are complementary colours. Seen in the wink of line one, then, is the colour that links that green eyeball to the green pie-shape or hat on the clown’s head, which is arguably the source of the “green flaunt” of line two. Perception, I suspect, is embodied in those lines midway through the poem where reading, the colour “red” (homophonically recalling past-tense “read”) and hot thoughts unfold; the figure in the painting might be seen as absorbing and assimilating the redness that dominates the background of the portrait. We’re moving here toward a view that is askew: crooked, out of position, oblique. Crookedness is enhanced by the sense that the figure in the painting is not quite singular: we can make two portraits from the line Klee has drawn down the middle of this face. It is unlikely that the portrait is of two people — the singular noun of the title suggests otherwise, and clowns are generally solitary, estranged creatures. I think Klee’s portrait depicts a masked clown, and this reading is consistent with Klee’s carnivalesque, early sketches, where masks often feature.11 Masks point to the fact that self can take on many guises; hence, perhaps, Klee’s display of this double-faced creature (both profile and frontal portrait) as firmly contained within the contours of the emphatically single, oval head. Due to facial expression and ruff, this clown is most likely a Pierrot. Stock characters in nineteenth-century and Expressionist art, Pierrots are riven by unrequited love, alienated to the point of madness, and the butt of pranks. Pierrots are naïve, trusting, and moonstruck, and Klee’s wistful, unsmiling clown betrays this pathos. Their capacity to quest and question may well be the source of the cloying queries in Forrest-Thomson’s poem, both of which follow moments of perception. Forrest-Thomson’s derision toward clear contours resurfaces on lines two and three of this poem: there are not enough shadows in this figure, which is jaunty, yet somehow constrained, boxed. But the curve of the green pie-shape intrigues, as it sidles into the angular division of the clown’s face. Deviance is stressed throughout: the “idle” of “curve idling” refers to something that leads to no solid result, vanity, foolishness. A leer is also indirect, a side glance; in its original, Old English usage, leer meant countenance, or face; as such, Forrest-Thomson’s “whatnot leer” nicely embodies the subject at hand — the portrait — and the newer sense of leer as “a look or roll of the eye expressive of slyness and malignity.” So too does the swerve of “nose swerve” suggest a turning aside, away from the straight or direct course, a deflection or transgression. Perception in the poem is askant, off-balance, and the avoidance of certainties is compounded by the term “whatnot,” which embodies a nondescript anything and everything. “Whatnot” can also be a euphemism for something the speaker does not want to name, which perhaps takes us back to deviance. Against these vacillations, the didactic sureness of the title, the winking, linked first line, and the flaunted jauntiness of the first stanza announce show, display, and liveliness. Forrest-Thomson’s love of unrealism arises in the “blue insinuate grin” of the third stanza. The “blue insinuate grin let[s] in” a view, seen within, askew; it is a curve that is artificial — it does not exist in the painting, where the blue mouth of the Pierrot is emphatically straight — but is internal, or central to the composition of the poem, which is consumed with deviating lines and curves even in its punctuation, its repetition of parentheses. To insinuate is to introduce by imperceptible degrees; Forrest-Thomson may suggest this is a clown on the verge of a smile. But insinuation means many things: it is subtle, artful, cunning, oblique, implied — as unreadable as the smile itself. And a “grin” may well be the smile at its most ambiguous: in Old English, “to grin” means to draw back the lips and show the teeth in pain, anger, or pleasure.12 The grin, then, embodies both comedy and tragedy; it is the arc-line of balanced momentum that Klee illustrates in his quest for a dynamic connection between extremes. And the speaker’s articulation of an implied grin is also very much in keeping with Klee’s thinking on artistic reception. Writing about the salutary effects of art, Klee claims that imagination “conjures up states of being that are somehow more encouraging and inspiring than those we know on earth or in our conscious dreams.” He adds that these unreal states indicate “[t]hat ethical gravity exists with impish tittering at doctors and priests” (80). In her interpretation of Klee’s painting, Forrest-Thomson conjures up the gravity and levity of a non-extant grin, a grin both implied and implying, even as it embodies the extremes of tragedy and comedy: the grin in “Clown” is a foray into unrealism that is both witty and balanced. Here we might pause to consider Klee’s description of balance, whilst keeping the physical act of grinning in mental view: The base broadens and with it the horizontal at the expense of the vertical. An appreciable relaxation sets in, an epic tempo as against the dramatic of the vertical, though, of course, this does not exclude the balancing of both sides. The vertical is still with us. Balance is excluded only when . . . the scales congeal, e.g. in the most primitive of structural rhythms, where there are only horizontal or vertical lines. (212) As in Klee’s description of a contour arising from a line, this passage delineates a broadening horizontal that recalls the sideways line of the mouth extending to a smile, and leading to a relaxed dynamism that keeps extremes — of emotional states, of levity and gravity — in view. Or as Forrest-Thomson puts it in another poem: “Value of forces in two dimensions / — equilibrium”; indeed, in this poem, balance is described as a means of “express[ing] unknown in known” — yet another unification of extremes (37). In “Clown,” the insinuated grin embodies Forrest-Thomson’s own delineation of creative flux, her suggestion that “what makes any work of art valuable is its dynamic expression of the inter-relation between subject/ object which is often expressed in the content/form tension” (164). “Clown (By Paul Klee)” strives to counterpoise dynamism and tension by exhibiting the physical pendulum swing of expression, pictorial and poetic, wistful and lively. Forrest-Thomson’s “Clown” aims to capture the “jaunty impulse” of Klee’s painting, and the way in which we — his audience and hers — are, to quote the poem, “looped (also) in” to a circuitous journey to an unqualified land of understanding. The line “looped (also) in” nicely gestures towards the extremes of a curve crossing itself, or a curvaceous journey that loops back to a new and different location — the final “and you?” of the poem leaves assessment of our arrival point up to us. The smile is multivalent; it captures extremes of anguish, derision, scorn, pleasure, joy, and affection. As Robert Motherwell writes, “there is a point on the curve of anguish where one encounters the comic. I think of Miró, of the late Paul Klee, of Charlie Chaplin, of what healthy human values their wit displays” (qtd in O’Hara). The duality of comic anguish in Klee’s art hangs suspended in Forrest-Thomson’s poem about Klee’s “Clown.” Forrest-Thomson is interested in the swing, motion, ambiguity and evanescence of the smile, rather than the clarity of the contour: at the end of her essay on Dada, she lauds some lines written by Tristan Tzara for their representation of “[t]he rhythm of the impersonal voice of language on the printed page” which “gives indeed neither joy nor sorrow, but only the curved archaic smile of an early Greek kouros” (92). Smiles are living, playful curved lines that delineate, but also, helpfully, deceive. As Klee writes in one of his poems, a “[s]mile of mutual comprehension” can rapidly disorient or distance; the line following this mutual smile reads: “Not everyone should decipher this, / else, alas / I’d be totally betrayed” (Watts 134). So, while many — arguably too many — of Forrest-Thomson’s curved lines and poetic journeys end in a kind of death-tinged stasis or onesided rigidity, I tend to read the suggestion in her “Individuals” that poetry “try / to straighten the spring” as satire (67). For, as in Klee’s aesthetics, Forrest-Thomson’s lines often are at their best when circuitous, even emphatically curved. Ultimately, the smile allows for an ambivalence that is more balanced — and more fruitfully and wittily open-ended — than the rigid incongruity said to catalyse laughter. Notes Unless otherwise noted, all Forrest-Thomson primary source quotations are drawn from Veronica Forrest-Thomson: Collected Poems. 2 For a history of this transcendental strain in laughter theory (of which Nietzsche and Bataille are the most famous proponents), see Barry Sanders’s Sudden Glory: Laughter as Subversive History; for a recent version of the same strain, see Diane D Davis, Breaking Up [at] Totality: A Rhetoric of Laughter. Arthur Koestler describes laughter as self-transcendence in The Act of Creation, and Hub Zwart gives it the status of truth in Ethical Consensus and the Truth of Laughter. 3 See “Sonnet” (141) and “The Garden of Proserpine” (139) respectively. 1 All definitions are drawn from the on-line OED. See, for instance, Arp’s “Notes from a Dada Diary,” where he discusses the relationship between Dada and nonsense, and claims that while Dada is pro-nonsense, this “does not mean bunk” (Motherwell 221-223). 6 Unless otherwise stated, all quotations from Klee’s aesthetics are drawn from Paul Klee Notebooks: The Thinking Eye. 7 Klee regularly, if inadvertently, uses the smile as an index of the world around us and its latent appeal: in a discussion of “natural measurement,” for instance, he mentions increase and decease, “and between them, culmination” (13). The sketch that results is the shape of a curved human mouth, turned on its side. This comic, inverted image is countered by an illustration of artificial measurement, which is akin to a blocky Mayan temple; by marked contrast, “natural measurement” is not constructed, but emerges from the fluidity of human expression. 8 A similar scepticism emerges in “Pastoral,” where “contours clear” of a country meadow and its clover do not compensate for names that are “jagged” and cannot be possessed, which “Remind us that the world is not ours.” Like modernists from Nietzsche forward, Forrest-Thomson exhibits enormous suspicion toward what she calls in this poem, “the frightful glare of nouns and nerves.” While the conflation of nouns and nerves here suggests that language is a part of the body, the poem ends with a contradictory reading in which language is emphatically tied to the artificiality of the machine: car brakes squealing are likened to “our twisted words” (123). In “Pastoral,” language is an unyielding, alien tool. 9 See “Provence” (24). 10 Forrest-Thomson also writes on another painting by Klee; both poem and painting are called “Landscape with Yellow Birds.” The painting in question emphasises playfulness — upside-down yellow birds feature throughout — and large swathes of organic, curved leaf shapes, much like sideways-on smiles, dominate the picture. Forrest-Thomson’s poem is concrete, experimental, and oblique; apart from her turn and return to Klee’s paintings with notable curved shapes, I am at a loss to generate any connective or significant reading of this poem. 11 See, for instance, Margaret Plant’s excellent book, Paul Klee: Figures and Faces, and particularly chapter two, “The Mask Face.” 12 The word “grin” is related to Old and Middle High German words grennan — to mutter or grunt — and grennan — to wail or grin. For etymological overview of grin and leer see Trumble 81-86. 4 5 Works Cited Arp, Jean. Collected French Writings: Poems, Essays, Memoirs. Ed. Marcel Jean. Trans. Joachim Neugroschel. London: John Calder, 2001. Ball, Hugo. Flight Out of Time: A Dada Diary. Ed. John Elderfield. Trans. Ann Raimes. NY: The Viking Press, 1974. Bergson, Henri. Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic. Trans. Cloudesley Bereton and Fred Rothwell. NY: Dover Publications, 2005. Breton, André, Paul Eluard, and Philippe Soupault. The Automatic Message, The Magnetic Fields, The Immaculate Conception. Trans by David Gascoyne, Antony Melville, & Jon Graham. London: Atlas Press, 1997. Davis, D. Diane. Breaking Up [at] Totality: A Rhetoric of Laughter. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 2000. Forrest-Thomson, Veronica. “Dada, Unrealism and Contemporary Poetry.” Twentieth-Century Studies (12): 1974. 77-92. ---. Poetic Artifice: A Theory of Twentieth-Century Poetry. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1978. ---. Veronica Forrest-Thomson: Collected Poems. Ed. Anthony Barnett. Exeter, UK: Shearsman Books Ltd, 2008. Klee, Paul. Paul Klee Notebooks: The Thinking Eye. Vol. 1. Trans. Ralph Manheim. London: Lund Humphries, 1961. ---. “Clown” (1929). Paul Klee. Ed. Carolyn Lanchner. NY: Museum of Modern Art, 1987, 229. Koestler, Arthur. The Act of Creation. London: Hutchinson, 1969. Motherwell, Robert, ed. The Dada Painters and Poets: An Anthology. NY: Wittenborn, Schultz, Inc., 1951. Plant, Margaret. Paul Klee: Figures and Faces. London: Thames and Hudson, 1978. Richter, Hans. Dada Art and Anti-Art. Trans. David Britt. London: Thames and Hudson, 2007. Frank O’Hara. Robert Motherwell. NY: MOMA, 1965. Sanders, Barry. Sudden Glory: Laughter as Subversive History. Boston: Beacon Press, 1995. Steinberg, Leo. Other Criteria: Confrontations with Twentieth-Century Art. NY: Oxford UP, 1972. Trumble, Angus. A Brief History of the Smile. NY: Basic Books, 2004. Watts, Harriet, ed and trans. Three Painter-Poets: Arp/Schwitters/Klee Selected Poems. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1974. Zwart, Hub. Ethical Consensus and the Truth of Laughter: The Structure of Moral Transformations. The Netherlands: Kok Pharos Publishing House Kampen, 1996.