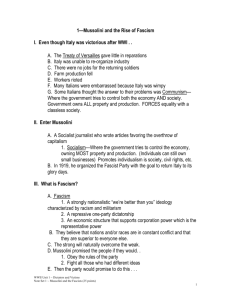

“A Mysterious Revival of Roman Passion”: Mussolini's Ambiguous

advertisement