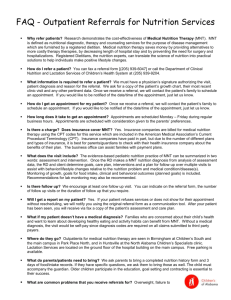

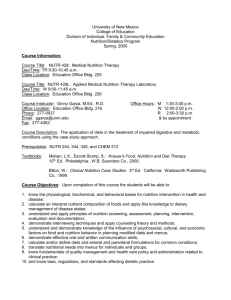

The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics National Coverage

advertisement