The Food and Drug Administration's Evolving

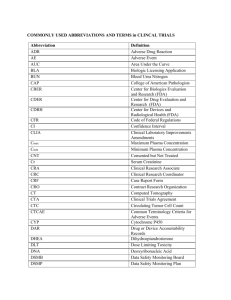

advertisement