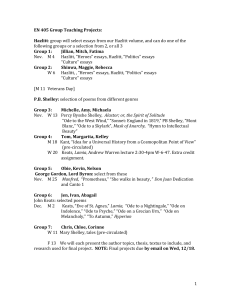

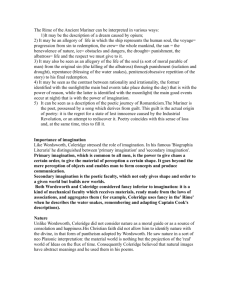

WILLIAM HAZLITT From On Shakespeare and Milton1

advertisement