course notes criminal law

advertisement

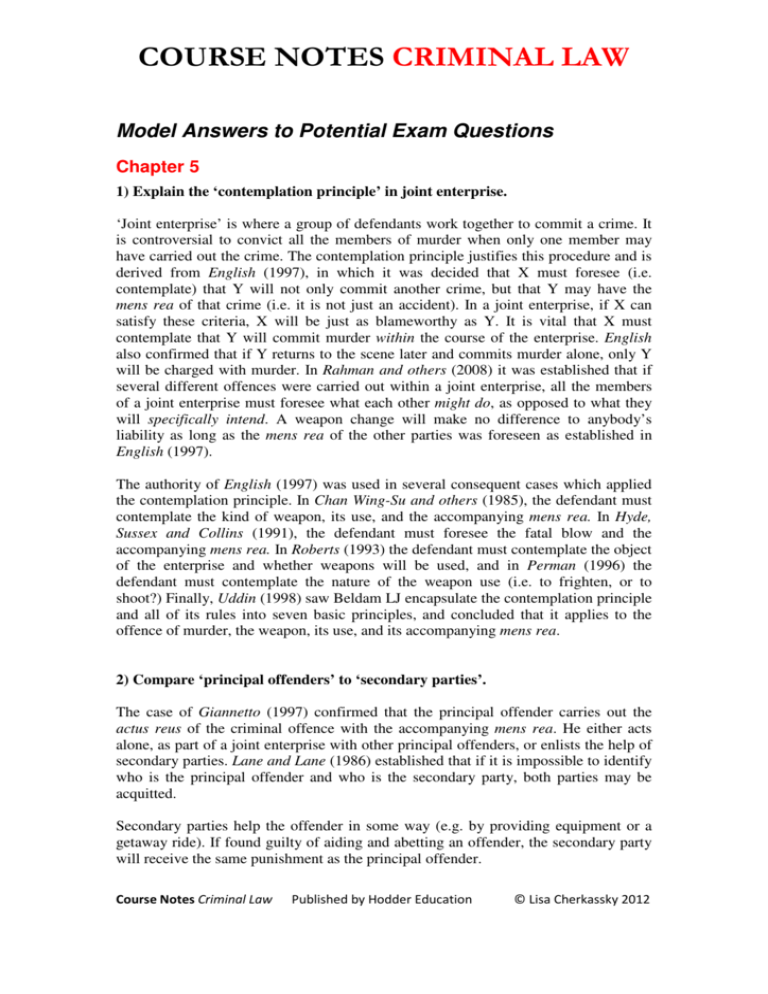

COURSE NOTES CRIMINAL LAW Model Answers to Potential Exam Questions Chapter 5 1) Explain the ‘contemplation principle’ in joint enterprise. ‘Joint enterprise’ is where a group of defendants work together to commit a crime. It is controversial to convict all the members of murder when only one member may have carried out the crime. The contemplation principle justifies this procedure and is derived from English (1997), in which it was decided that X must foresee (i.e. contemplate) that Y will not only commit another crime, but that Y may have the mens rea of that crime (i.e. it is not just an accident). In a joint enterprise, if X can satisfy these criteria, X will be just as blameworthy as Y. It is vital that X must contemplate that Y will commit murder within the course of the enterprise. English also confirmed that if Y returns to the scene later and commits murder alone, only Y will be charged with murder. In Rahman and others (2008) it was established that if several different offences were carried out within a joint enterprise, all the members of a joint enterprise must foresee what each other might do, as opposed to what they will specifically intend. A weapon change will make no difference to anybody’s liability as long as the mens rea of the other parties was foreseen as established in English (1997). The authority of English (1997) was used in several consequent cases which applied the contemplation principle. In Chan Wing-Su and others (1985), the defendant must contemplate the kind of weapon, its use, and the accompanying mens rea. In Hyde, Sussex and Collins (1991), the defendant must foresee the fatal blow and the accompanying mens rea. In Roberts (1993) the defendant must contemplate the object of the enterprise and whether weapons will be used, and in Perman (1996) the defendant must contemplate the nature of the weapon use (i.e. to frighten, or to shoot?) Finally, Uddin (1998) saw Beldam LJ encapsulate the contemplation principle and all of its rules into seven basic principles, and concluded that it applies to the offence of murder, the weapon, its use, and its accompanying mens rea. 2) Compare ‘principal offenders’ to ‘secondary parties’. The case of Giannetto (1997) confirmed that the principal offender carries out the actus reus of the criminal offence with the accompanying mens rea. He either acts alone, as part of a joint enterprise with other principal offenders, or enlists the help of secondary parties. Lane and Lane (1986) established that if it is impossible to identify who is the principal offender and who is the secondary party, both parties may be acquitted. Secondary parties help the offender in some way (e.g. by providing equipment or a getaway ride). If found guilty of aiding and abetting an offender, the secondary party will receive the same punishment as the principal offender. Course Notes Criminal Law Published by Hodder Education © Lisa Cherkassky 2012 COURSE NOTES CRIMINAL LAW 3) Distinguish ‘aiding’, ‘abetting’, ‘counselling’ and ‘procuring’. Secondary parties who help principal offenders will be charged under section 8 of the Accessories and Abettors Act 1861: “Whosoever shall aid, abet, counsel or procure the commission of any indictable offence is liable to be tried, indicted and punished as a principal offender.” It is not entirely clear what aid, abet, counsel or procure means, but the lords have encouraged judges to give them their “ordinary meaning if possible” — Attorney-General’s Reference (No 1 of 1975) (1975). For the purposes of aiding, living together does not provide assistance. Assistance requires more than mere knowledge as held in Bland (1988). In addition, although more than mere knowledge is required, the secondary party does not have to be at the scene of the crime to be convicted of aiding. For abetting, any involvement from mere encouragement upwards is required, but being present at the scene is essential. In Coney and others (1882) a defendant may encourage intentionally by expressions, gestures or actions intended to signify approval. A secret intention to join in is not enough as held in Allan (1965). Merely watching an attack is not enough — Clarkson and others (1971). Voluntary presence in a crowd can abet an offender as seen in Wilcox v Jeffrey (1951). An omission can abet a principal offender if the abettor has knowledge of the facts and a duty to control the principal but does not according to Tuck v Robson (1970). In order to counsel a principal offender, according to Calhaem (1985) there must be contact between parties and a connection between counselling and the offence committed. Constant pressure will also suffice as held in Luffman (2008). Procuring can mean “causing” and this can include an act or a word that causes a criminal act to be committed: Attorney-General’s Reference (No 1 of 1975) (1975) preferred the term “produce by endeavour”. In Millward (1994) the defendant was found not to have “endeavoured” the result but he did “cause” it. 4) Discuss the mens rea requirement for secondary parties. When aiding, abetting, counselling or procuring a principal offender, the secondary party must intend to aid, abet, counsel or procure the principal offender (as in National Coal Board v Gamble 1959); know of the circumstances that make up the criminal offence, and know of the principal offender’s mens rea at the time of the offence. As far as intention is concerned, a guilty mind is essential for secondary parties and medical treatment will negate a guilty mind as held in Gillick (1986). Regarding knowledge of circumstances, the secondary party must at least know the essential matters which constitute the offence but he need not actually know that an offence has been committed as seen in Youden and others (1950). It is not necessary to prove that the secondary party had knowledge of the precise crime or the particular crime, however, he must know more than “some illegal venture” — Bainbridge (1960). A defendant will be convicted of aiding and abetting an offence which is “within his contemplation” as established in DPP of Northern Ireland v Maxwell (1978). Course Notes Criminal Law Published by Hodder Education © Lisa Cherkassky 2012 COURSE NOTES CRIMINAL LAW The “contemplation principle” requires a secondary party to foresee the principal’s mens rea at the time of the offence in order to be convicted of aiding and assisting that particular offence — English (1997). 5) Define ‘effective withdrawal’ in joint liability using legal authorities to illustrate your answer. If an accessory or a participant in a joint enterprise wishes to withdraw from the venture, he may do so and escape liability for the full offence. The accessory or participant may still be liable for other offences up to that point. Dunn LJ in Whitefield (1984) confirms that words without action is not enough (i.e. simply “saying” that he wants to leave): “Serve unequivocal notice upon the other party to the common unlawful cause that if he proceeds upon it he does so without the further aid and assistance of those who withdraw”. A similar decision was reached in Eldredge v United States (1932) by McDermott J: “A declared intent to withdraw from a conspiracy to dynamite a building is not enough, if the fuse has been set, he must step on the fuse”. Something “vastly different and vastly more effective” is required than jumping out of a window and running away according to Becerra and Cooper (1975). Communication must be “unequivocal” (i.e. plain and clear) as seen in Rook (1993). Stating an intention to withdraw and then moving away if the criminal act has already commenced is not enough as held in Baker (1994). If the criminal act is spontaneous (i.e. not pre-planned), walking away will suffice as “effective communication” of withdrawal as established in Mitchell and King (1998). Leaving the scene of a street fight will be an effective withdrawal as confirmed in O’Flaherty and others (2004). A mere “lull” in a violent attack does not constitute a withdrawal, a participant must have demonstrably withdrawn - Mitchell (2008). Course Notes Criminal Law Course Notes Criminal Law Published by Routledge Published by Hodder Education © Lisa Cherkassky 2012 © Lisa Cherkassky 2012