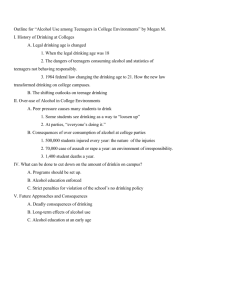

M - Icap

advertisement

MODULE 8: “AT-RISK” POPULATIONS Summary: • • • • • • • • “At-risk” populations include those individuals who are particularly susceptible to the harmful effects of alcohol due to intrinsic or external factors. Risk for harm may be the result of an individual’s own drinking, that of others, or lifestyle factors. Genetic difference, general health status, mental health, age, and gender may all contribute to heightened risk. For some people social and economic circumstances increase the risk for harm. “At-risk” populations require policy approaches that allow for prevention and intervention that are realistic and correspond to prevailing drinking patterns, circumstances, and cultural needs. Where “at-risk” groups are hard to reach, special interventions relying on non-traditional approaches may be necessary. Interventions tailored to the needs of “at-risk” groups should be taken into account and integrated into the provision of general healthcare services to the extent possible—including education, screening, and treatment. For EXAMPLES OF TARGETED INTERVENTIONS, see the Blue Book index page of www.icap.org. “At-risk” or “special” populations include a broad and diverse range of individuals who are deemed to be particularly susceptible to either the physical or psychological effects of alcohol and are, thus, more likely than others to experience adverse outcomes of drinking. For some, harm may be the result of their own drinking. For others, heightened risk may be related to the drinking of those around them. Together, these groups represent a particular cause for public health concern and serve as specific targets for interventions and prevention measures (see also MODULE 9: Women and Alcohol; MODULE 11: Young People and Alcohol; MODULE 17: Alcohol Dependence and Treatment; MODULE 23: Alcohol and the Elderly). Intrinsic risk factors Risk factors related to drinking may be grouped into two basic categories: intrinsic and environmental. Factors that are biological and endogenous in nature fall under the former category. Genetics Genetic differences in the ability to metabolize alcohol and in physiological responses to it may increase the risk of negative outcomes of drinking for some people (Begleiter & Porjesz, 1995, 1999; International Center for Alcohol Policies, 2001). 1 They may also underlie variations in how the brain and neurotransmitter systems respond when exposed to alcohol (Begleiter & Porjesz, 1995; Loh & Ball, 2000). These differences may manifest themselves as low tolerance to alcohol and the inability for the body to break it down effectively (Goedde et al., 1992; Wall & Ehlers, 1995; Wall, Horn, Johnson, Smith, & Carr, 2000). For example, among some ethnic groups— notably Asians of Chinese, Korean, and Japanese descent—genetic variation in the enzyme responsible for breaking down alcohol and eliminating it from the body, aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), is fairly common (e.g., Maezawa, Yamauchi, Toda, Suzuki, & Sakurai, 1995 ; Smith, 1986; Wall et al., 2000). Similar variations are also found among some Ashkenazi Jews, Native 1 See ANNEX 2: The Basics about Alcohol for an overview of the mechanism by which alcohol is broken down in the body. Americans, and certain indigenous populations in South America (Gill, Elk, Liu, & Deitrich, 1999; Neumark et al., 2004). Physiological symptoms that may follow alcohol consumption for these individuals include nausea, dizziness, heart palpitations, and a “flushing” reaction. Increased risk for alcohol abuse or dependence in some individuals is also attributable to genetic factors (MODULE 17: Alcohol Dependence and Treatment; e.g., Heilig & Sommer, 2004; Sommer, Arlinde, & Heilig, 2005). This heightened susceptibility is often transmitted across generations within families (Ehlers, Slutske, Gilder, Lau, & Wilhelmsen, 2006; Goodwin, 1985; Haber, Jacob, & Heath, 2005; Schuckit et al., 2000). However, the same genetic differences that underlie differential risk for harm may also provide an opportunity for screening and prevention. Certain traits may serve as markers for “at-risk” individuals. Characteristic brain activity, certain personality traits, and a high tolerance for alcohol may be useful in identifying those individuals likely to develop dependence later in life (Porjesz & Begleiter, 1998; Schuckit & Smith, 2001; Soloff, Lynch, & Moss, 2000). Health status The effects of alcohol are closely linked to the health and nutrition status of the drinker. Thus, individuals who are malnourished may be particularly susceptible to adverse outcomes, an issue closely related to socioeconomic considerations (Marmot & Wilkinson, 1999; see section on “Socioeconomic Issues” below). Indeed, neurological impairment among heavy chronic drinkers and alcohol-dependent individuals has been linked to nutritional deficiencies (e.g., Manzo, Locatelli, Candura, & Costa, 1994; Thomson & Cook, 2000). Certain medical conditions can increase the potential risk associated with alcohol consumption. Although moderate drinking has been shown to have a beneficial effect on some individuals with Type II diabetes mellitus, for others even moderate alcohol intake may induce low blood sugar levels (hypoglycemia) and heavy drinking can result in serious health consequences (Emanuele, Swade, & Emanuele, 1998). Hypertensive individuals may be adversely affected by drinking, and those infected with hepatitis C may be at risk for accelerated liver disease if they consume alcohol (Beilin, 1995; Beilin, 2004; Regev & Jeffers, 1999; Wakim-Fleming & Mullen, 2005). The interaction of alcohol with a range of medications may also heighten the risk for harm. Alcohol intake may reduce the effectiveness of some medications and even have dangerous effects (Ramskogler et al., 2001; Sternbach & State, 1997). In particular, adverse interactions have been described for analgesics, antihistamines, anticoagulants, psychopharmacologically active drugs, anti-hypertensive medication, and antibiotics (Weathermon & Crabb, 1999). Such potentially harmful interactions present a particular concern for older individuals who are more likely than younger people to take medications and whose health status may generally be weakened (see MODULE 23: Alcohol and the Elderly). There is evidence that individuals with certain mental health problems are also at increased risk for alcohol abuse and adverse outcomes. Comorbidity with alcohol abuse has been reported for a number of mental health conditions, including panic and anxiety disorders, depression, and bipolar disorder, especially among those who lack adequate access to support (Alati et al., 2005; Beals et al., 2005; Pashall, Freistheler, & Lipton, 2005). Attention-deficit / hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children may be a predictor for alcohol abuse and dependence later in life (Schubiner, 2005; Wilens, 1998). These findings support the notion that alcohol abuse and mental health disorders share a common genetic linkage. They also suggest that, where comorbidity is evident, special interventions may be needed (see MODULE 17: Alcohol Dependence and Treatment; e.g., Schubiner, 2005; Sher et al., 2005). 8-2 Updated: January 2006 Available at: www.icap.org Alcohol abuse and dependence Individuals with abusive drinking patterns are at increased risk for both health and social harm. This applies as much to those who are alcohol-dependent as to those who are not (see MODULE 17: Alcohol Dependence and Treatment). Chronic heavy drinkers, for example, are more likely to develop hepatic disease, including liver cirrhosis, and neurological problems (Harper & Matsumoto, 2005; McKillop & Schrum, 2005; Sougioultzis, Dalakas, Hayes, & Plevris, 2005; Willner & Reuben, 2005). A range of social risks related to family life or the workplace are also more commonly found among these individuals than among other groups (Boyd & Mackey, 2000; Haw, Hawton, Casey, Bale, & Shepherd, 2005; Hornquist & Akerlind, 1987). The risk of acute problems—including accidents and injuries—is also increased with alcohol abuse and such drinking patterns as binge drinking and intoxication (Cherpitel et al., 2006; Moore, 2005; Salome, French, Matzger, & Weisner, 2005). Age Young people are considered to be “at risk” for harm from alcohol for several reasons. Children and adolescents, for example, may have increased sensitivity to the effects of alcohol due to specific changes in physiological development (Abate, Spear, & Molina, 2005; Chung, Martin, Winters, & Langenbucher, 2001; Koob et al., 1998; Spear, 2004). Young people’s inexperience with alcohol and inability to gauge and enforce their own limits increase the potential risk for harm, especially where drinking is paired with other activities, for example, driving (see MODULE 15: Drinking and Driving). Adolescence is generally a period for experimentation when young people take risks and test their own limits. These factors contribute the risk young people may experience from drinking (see MODULE 11: Young People and Alcohol). There is also evidence suggesting that young people who begin drinking at an early age may be at greater risk for alcohol problems later in life (Maggs & Schulenberg, 2005; Pitkanen, Lyyra, & Pulkkinen, 2005; Warner & White, 2003). However, the nature of this relationship has not been clearly identified. Drinking culture, family, and social context are all likely to play a role in whether risk is elevated (Baumeister & Tossmann, 2005; Kuperman et al., 2005; Pitkanen et al., 2005). The elderly are also considered an “at-risk” group when it comes to alcohol (see MODULE 23: Alcohol and the Elderly). Although drinking in moderation has been linked to health benefits for the elderly, some older people are at increased risk for harm. The ageing process is associated with physiological changes, such as a reduction in body water content, decreased hepatic blood flow, and a reduced efficiency in the metabolism of alcohol (Scott, 1989). The pharmacological interaction of alcohol with various medications also increases risk in the elderly. The stresses of ageing, loneliness, and various lifestyle changes in this group further increase their risk for alcohol abuse and harm. Gender Women, particularly pregnant women, are generally identified as an “at-risk” population in terms of alcohol consumption. The physiological differences between women and men influence their respective abilities to metabolize alcohol and mean that the harm threshold for women may be lower than that for men (see ANNEX 2: The Basics about Alcohol). The need to provide access to gender-sensitive prevention and treatment has been recognised. Some of these approaches, as they relate to both women and pregnancy, are discussed in MODULE 9: Women and Alcohol and MODULE 10: Drinking and Pregnancy. 8-3 Updated: January 2006 Available at: www.icap.org Environmental factors External factors also play an important role in determining the degree of risk an individual is likely to experience from his or her own drinking, as well as from the drinking of others. Parental drinking There is evidence that parental alcohol consumption plays a significant role in the drinking behaviour of offspring, both in establishing positive patterns and in increasing risk for harm (e.g., Houghton & Roche, 2001). Drinking problems among parents are predictive of elevated risk for similar problems in children. In general, those whose parents are alcohol-dependent are more likely to themselves be dependent or abusive drinkers (Chalder, Elgar, & Bennett, 2006; Kuperman et al., 2005; Pulkkinen & Pitkanen, 1994). It should be noted that many parental influences beyond drinking have a profound effect on the development of drinking behaviors and potential problems in young people (MODULE 11: Alcohol and Young People; e.g., El-Sheikh & Buckhalt, 2003). Another aspect of parental drinking relates to alcohol consumption during pregnancy and the increased risk for harm this may represent, as discussed in MODULE 10: Drinking and Pregnancy. Stress Stress of various types—including that associated with traumatic events or situations, work stress, abuse, and issues related to maturation and ageing—may contribute to the development of drinking problems (e.g., Anisman & Merali, 1999; Pulkkinen & Pitkanen, 1994; Ragland, Greiner, Yen, & Fisher, 2000; Sawchuk et al., 2005). The body’s response to pressure at the physiological and psychological levels exacerbates risk for harm from alcohol consumption. There is evidence that some individuals who are under stress, especially for prolonged periods of time, may be at increased risk for problems relating to their drinking, as many of them may consume alcohol in order to cope (Sayette, 1999). Socioeconomic issues Risk exposure is directly related to access to nutrition, health care, education, and a social network. Where any of these is inadequate, risk for harm in general is heightened, including harm related to drinking. The poor tend to be more susceptible to harm and have fewer means of coping adequately with risk. Alcohol problems and abuse may be often observed as side-effects of social deprivation (e.g., Lee & Jeon, 2005; Subramanian, Nandy, Irving, Gordon, & Smith, 2005). Access to intervention—whether specific to alcohol problems or to health care in genera—is largely limited or even entirely non-existent for these populations. Social exclusion and marginalization are also identified risk factors for alcohol abuse. Indigenous populations and certain ethnic and social groups in some countries are often outside the mainstream of society, generally enjoy lower socioeconomic status, and inadequate access to health care and other services (e.g., Alaniz, 2005; Brady, 2000; Ehlers et al., 2006; Hughes, 2005; MODULE 24: HIV/AIDS, High-risk Behaviors, and Risky Drinking Patterns). Professions and workplace Individuals in a number of professions may be at increased risk for alcohol-related harm. Among them are those involved in the production and service of beverage alcohol. There is evidence that individuals involved in the retail sector of the beverage alcohol industry, notably those working in pubs and bars, may have higher risk for alcohol abuse than the general population (reviewed in International Center for Alcohol Policies, 2003). 8-4 Updated: January 2006 Available at: www.icap.org Professions with high levels of stress may also place those working in them at risk for alcohol abuse and other problems. These include law enforcement, as well as professions exposed to high rates of occupational hazards, such as chemical or biological substances, physical hazards, injury risk, and mental stress (e.g., Conrad, Furner, & Qian, 1999; Davey, Obst, & Sheehan, 2000). Journalists have been reported as having a higher incidence of alcohol problems compared to those in other professions, as have military personnel and doctors (e.g., Cosper & Hughes, 1982; Engel et al., 1999; Kumar & Basu, 2000). Policy considerations Because of their heightened susceptibility for harm, “at-risk” populations represent specific targets for interventions and policy. Approaches that are sufficient to address the needs of the general population may not adequately address theirs. Carefully tailored approaches should be considered to ensure that the risk for harm to each of the groups outlined above can be minimized. Data collection Any policies aimed at particular “at-risk” groups require a sound understanding of the actual drinking patterns and problems among these populations. This argues for the collection of detailed information so that appropriate measures can be developed. Some “at-risk” populations are socially marginalized and thus difficult to access, which is one of the reasons risk for them in increased. For instance, those who belong to particular ethnic or indigenous groups may not be fluent in the “official” language of the country or have a stable residence. Creative approaches are therefore needed to reach these populations in a way that is sensitive to their particular cultures and utilizes relevant social networks and venues. Thus, pharmacists, social workers, or individuals working in shelters may be well placed to collect information and could be trained to do so. Where data are already collected on risk groups’ health and social issues, attention to drinking patterns and outcomes would be a useful addition. Prevention An important element in prevention is educating those at risk about drinking and its potential outcomes. Alcohol education includes informing key audiences about risks, benefits, and related issues, raising their awareness and ultimately attempting to change behavior. It is provided through a range of channels (see MODULE 1: Alcohol Education), but, in the case of “at-risk” populations, careful tailoring should be considered both in terms of the channels that are used and the messages conveyed through them. Prevention efforts, including education, should strive to be delivered in a way that is meaningful to target groups, will resonate with them, and make sense. There is also evidence that prevention measures that empower individuals receiving them and allow active participation may be of particular value. For example, peer education and the involvement of family in intervention and/or treatment could be effective approaches when dealing with young people. Prevention also requires the use of appropriate channels most likely to reach intended audiences. Schools offer a convenient setting for information dissemination and awareness building among young people, although the effectiveness of these efforts has been debated. Prevention can also be targeted through venues that are likely to be frequented by “at-risk” groups—for instance, social or athletic clubs and organizations, youth groups, shelters for the homeless or abused, emergency rooms, foster care, soup kitchens, and others. The workplace also offers a powerful approach to preventing harm for “at-risk” drinkers through training, awareness building, education and the provision of counseling and treatment services. 8-5 Updated: January 2006 Available at: www.icap.org Codes of practice and regulations on alcohol and the workplace, when properly enforced, are useful measures for preventing harm. Where “at-risk” groups are particularly hard to reach, unconventional approaches may be most effective. For example, reliance on radio and television broadcasts may be advisable where illiteracy rates are high. Theatre groups have also been helpful in conveying certain key messages. This approach has been used in developing countries when focusing on several areas of health (e.g., MODULE 24: HIV/AIDS, High-risk Behaviors, and Risky Drinking Patterns). If language proficiency is a problem—for instance, among indigenous populations, immigrant, and/or various ethnic groups—messages should also be conveyed in the language with which the target population is most comfortable and in a way that is culturally appropriate. Attention may need to be given to who conveys the message. Among Native American populations, for example, involving community elders may increase he likelihood that messages will be received. Finally, the success of interventions also hinges upon whether those who provide them understand the issues they are meant to address and can communicate effectively with their targets. This necessitates appropriate training of health professionals, social workers, educators, and others in close contact with “at-risk” groups. Again, dealing with such populations requires an understanding of key issues, sensitivities, and the reality of the drinking behavior and problems among target groups. Screening and intervention The identification of those at particular risk for harm relies on effective screening. Individuals at risk for alcohol abuse and dependence can be assessed through several useful instruments, including the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), which has been validated crossculturally (MODULE 17: Alcohol Dependence and Treatment; MODULE 18: Early Identification and Brief Intervention). In many cases, only brief intervention that modifies potentially harmful drinking patterns may be necessary. The primary health care setting offers an appropriate venue for such screening, as do emergency rooms, practices of general practitioners, general health services, social services, or other facilities that are at the disposal of different groups whose risk for harm may be elevated. Appropriate and affordable treatment for individuals identified as “at-risk” for alcohol problems is an integral part of any comprehensive policy. Treatment providers need to be aware of the particular needs, cultural requirements, and lifestyle issues of the “at-risk” groups they are likely to encounter. Where possible, integrating treatment for alcohol problems into the general provision of health care is preferable. Primary health providers, educators, social workers, and others can also be instrumental in screening individuals at risk for harm from others’ drinking or certain lifestyle factors. Recognizing the signs of abuse, stress, or other hazards can help identify “at-risk” individuals and offer means for intervention. Conclusions Individuals who are at increased risk for harm from drinking require special attention with regard to prevention and intervention measures as compared to the general population. As they are often outside of the mainstream with regard to health care and access to resources, reaching them may present a policy challenge. However, balanced policies around alcohol should also take “at-risk” groups into account, including special provisions for understanding and meeting their needs. Particularly in countries where social disparities are common and related to disparities in access to proper care, greater attention is needed to identifying and protecting those most at risk. 8-6 Updated: January 2006 Available at: www.icap.org POLICY OPTIONS: “At-risk” Populations In developing policies and approaches, consideration of a number of key elements is required. While some may be necessary at a minimum and under most conditions, others may not be appropriate in all cases, or may be difficult to implement. The list below offers a menu of areas that need to be addressed, based on effective approaches that have been implemented elsewhere. Specific examples are provided in the TARGETED INTERVENTIONS section of the ICAP Blue Book. Information Collection of detailed information on “at-risk” groups, their drinking patterns, and health outcomes through general surveys and in venues where access to these populations is possible. Provision of tailored information: education about drinking patterns and outcomes. • Realistic information within the context of the lives of “at-risk” groups. • Culturally sensitive information and delivery. • Inclusive approaches that empower those at risk. • Realistic and achievable goals and behavior modifications. Access to prevention and treatment Provision of adequate health care and screening where “at-risk” groups can be reached (e.g., prenatal care, shelters, soup kitchens). • Train health professionals, social workers, and educators to provide guidance and advice applicable and relevant to “at-risk” groups. • Sensitivity to particular social and health issues that may obscure drinking problems. • Where mainstream access is unavailable, alternative methods should be explored. • Ensure availability of screening tools appropriate for individual sub-populations at risk (e.g., the elderly, young people). Special considerations • Access to prevention and treatment through the workplace, including screening for problems and brief interventions. • Culturally appropriate access and interventions for indigenous populations and ethnic groups outside the social mainstream. • Attention to cultural context and views on drinking, language considerations. • Implementation of non-traditional approaches for hard-to-reach groups that rely on alternative means of communication (e.g., illiterate individuals). 8-7 Updated: January 2006 Available at: www.icap.org References Abate, P., Spear, N. E., & Molina, J. C. (2005). Foetal and infantile alcohol-mediated associative learning in the rat. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 25, 989–998. Alaniz, M. L. (2005). Migration, acculturation, displacement: Migratory workers and "substance abuse." Substance Use and Misuse, 37, 1253–1257. Alati, R., Lawlor, D. A., Najman, J. M., Williams, G. M., Bor, W., & O'Callaghan, M. (2005). Is there really a "J-shaped" curve in the association between alcohol consumption and symptoms of depression and anxiety? Findings from the Mater-University Study of Pregnancy and its outcomes. Addiction, 100, 643–651. Anisman, H., & Merali, Z. (1999). Understanding stress: Characteristics and caveats. Alcohol Research and Health, 23, 241–249. Baumeister, S. E., & Tossmann, P. (2005). Association between early onset of cigarette, alcohol and cannabis use and later drug use patterns: An analysis of a survey in European metropolises. European Addiction Research, 11, 92–98. Beals, J., Novins, D. K., Whitesell, N. R., Spicer, P., Mitchell, C. M., & Manson, S. M. (2005). Prevalence of mental disorders and utilization of mental health services in two American Indian reservation populations: Mental health disparities in a national context. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 1723–1732. Begleiter, H., & Porjesz, B. (1995). Neurophysiological phenotypic factors in the development of alcoholism. In H. Begleiter & B. Kissin (Ed.), Genetics of Alcoholism (pp. 269–293). New York: Oxford University Press. Begleiter, H., & Porjesz, B. (1999). What is inherited in the predisposition toward alcoholism? A proposed model. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 23, 1125–1135. Beilin, L. J. (1995). Alcohol and hypertension. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology, 22, 185–188. Beilin, L. J. (2004). Update on lifestyle and hypertension control. Clinical and Experimental Hypertension, 26, 739–746. Boyd, M. R., & Mackey, M. C. (2000). Alienation from self and others: The psychosocial problem of rural alcoholic women. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 14, 134–141. Brady, M. (2000). Alcohol policy issues for indigenous people in the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Contemporary Drug Problems, 27, 435–509. Chalder, M., Elgar, F. J., & Bennett, P. (2006). Drinking and motivations to drink among adolescent children of parents with alcohol problems. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 41, 107– 113. Chandler, L. S., Richardson, G. A., Gallagher, J. D., & Day, N. L. (1996). Prenatal exposure to alcohol and marijuana: Effects on motor development of preschool children. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 20, 455–461. Cherpitel, C. J., Bond, J., Ye, Y., Borges, G., Room, R., Poznyak, V., et al. (2006). Multi-level analysis of causal attribution of injury to alcohol and modifying effects: Data from two international emergency room projects. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 82, 258–268. Chung, T., Martin, C. S., Winters, K. C., & Langenbucher, J. W. (2001). Assessment of alcohol tolerance in adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 62, 687–695. Conrad, K. M., Furner, S. E., & Qian, Y. (1999). Occupational hazard exposure and at risk drinking. AAOHN Journal, 47, 9–16. Cosper, R., & Hughes, F. (1982). So-called heavy drinking occupations; two empirical tests. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 43, 110-118. Davey, J. D., Obst, P. L., & Sheehan, M. C. (2000). Work demographics and officers' perceptions of the work environment which add to the prediction of at risk alcohol consumption within an Australian police sample. Policing-An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 23, 69–81. Ehlers, C. L., Slutske, W. S., Gilder, D. A., Lau, P., & Wilhelmsen, K. C. (2006). Age at first intoxication and alcohol use disorders in southwest California Indians. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 30, 1856–1865. 8-8 Updated: January 2006 Available at: www.icap.org El-Sheikh, M., & Buckhalt, J. A. (2003). Parental problem drinking and children's adjustment: Attachment and family functioning as moderators and mediators of risk. Journal of Family Psychology, 17, 510–520. Emanuele, N. V., Swade, T. F., & Emanuele, M. A. (1998). Consequences of alcohol use in diabetics. Alcohol Health and Research World, 22, 211–219. Engel, C. C., Ursano, R., Magruder, C., Tartaglione, R., Jing, Z., Labbate, L. A., et al. (1999). Psychological conditions diagnosed among veterans seeking Department of Defense care for Gulf War-related health concerns. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 41, 384–392. Gill, K., Elk, M. E., Liu, Y., & Deitrich, R. A. (1999). An examination of ALDH2 genotypes, alcohol metabolism and the flushing response in Native Americans. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 60, 149–158. Goedde, H. W., Agarwal, D. P., Fritze, G., Meier-Tackmann, D., Singh, S., Beckmann, G., et al. (1992). Distribution of ADH sub2 and ALDH sub2 genotypes in different populations. Human Genetics, 88(3), 344-346. Goodwin, D. W. (1985). Alcoholism and genetics: The sins of the fathers. Archives of General Psychiatry, 42, 171–174. Haber, J. R., Jacob, T., & Heath, A. C. (2005). Paternal alcoholism and offspring conduct disorder: Evidence for the "common genes" hypothesis. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 8, 120–131. Harper, C., & Matsumoto, I. (2005). Ethanol and brain damage. Current Opinion in Pharmacology, 5(1), 73-78. Haw, C., Hawton, K., Casey, D., Bale, E., & Shepherd, A. (2005). Alcohol dependence, excessive drinking and deliberate self-harm. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 40, 964–971. Heilig, M., & Sommer, W. (2004). Functional genomics strategies to identify susceptibility genes and treatment targets in alcohol dependence. Neurotoxicology Research, 6, 363–372. Hill, S. Y., Steinhauer, S. R., & Zubin, J. (1992). Cardiac responsivity in individuals at high risk for alcoholism. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 53(4), 378-388. Hornquist, J. O., & Akerlind, I. (1987). Loneliness correlates in advanced alcohol abusers. II. Clinical and psychological factors. Scandinavian Journal of Social Medicine, 15, 225–232. Houghton, E., & Roche, A. M. (Eds.). (2001). Learning about drinking. New York: BrunnerRoutledge. Hughes, T. L. (2005). Alcohol use and alcohol-related problems among lesbians and gay men. Annual Review of Nursing Research, 23, 283–325. International Center for Alcohol Policies (ICAP). (2001). Alcohol and “special populations”: Biological vulnerability. ICAP Report 10. Washington, DC: Author. International Center for Alcohol Policies (ICAP). (2003). Alcohol and the workplace. ICAP Report 13. Washington, DC: Author. Koob, G. F., Roberts, A. J., Schulteis, G., Parsons, L. H., Heyser, C. J., Hyytia, P., et al. (1998). Neurocicuitry targets in ethanol reward and dependence. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 22, 3–9. Kumar, P., & Basu, D. (2000). Substance abuse by medical students and doctors. Journal of Indian Medical Association, 98, 447–452. Kuperman, S., Chan, G., Kramer, J. R., Bierut, L., Bucholz, K. K., Fox, L., et al. (2005). Relationship of age of first drink to child behavioral problems and family psychopathology. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 29(10), 1869-1876. Lee, S. G., & Jeon, S. Y. (2005). [The relations of socioeconomic status to health status, health behaviors in the elderly]. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, 38, 154–162. Loh, E. W., & Ball, D. (2000). Role of the GABA(A)beta2, GABA(A)alpha6, GABA(A)alpha1 and GABA(A)gamma2 receptor subunit genes cluster in drug responses and the development of alcohol dependence. Neurochemistry International, 37, 413–423. Maezawa, Y., Yamauchi, M., Toda, G., Suzuki, H., & Sakurai, S. (1995 ). Alcohol-metabolizing enzyme polymorphisms and alcoholism in Japan. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 19, 951–954. 8-9 Updated: January 2006 Available at: www.icap.org Maggs, J. L., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2005). Initiation and course of alcohol consumption among adolescents and young adults. Recent Developments in Alcoholism, 17, 29–47. Manzo, L., Locatelli, C., Candura, S. M., & Costa, L. G. (1994). Nutrition and alcohol neurotoxicity. Neurotoxicology, 15, 555–556. McKillop, I. H., & Schrum, L. W. (2005). Alcohol and liver cancer Alcohol, 35(3), 195-203. Moore, E. E. (2005). Alcohol and trauma: The perfect storm. Journal of Trauma-Injury Infection and Critical Care, 59, S53–S56. Neumark, Y. D., Friedlander, Y., Durst, R., Leitersdorf, E., Jaffe, D., Ramchandani, V. A., et al. (2004). Alcohol dehydrogenase polymorphisms influence alcohol-elimination rates in a male Jewish population. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 28, 10–14. Pashall, M. J., Freistheler, B., & Lipton, R. I. (2005). Moderate alcohol use and depression in young adults: Findings from a national longitudinal survey. American Journal of Public Health, 95, 453–457. Pitkanen, T., Lyyra, A. L., & Pulkkinen, L. (2005). Age of onset of drinking and the use of alcohol in adulthood: A follow-up study from age 8-42 for females and males. Addiction, 100, 652–661. Porjesz, B., & Begleiter, H. (1998). Genetic basis of event-related potentials and their relationship to alcoholism and alcohol use. Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology, 15(1), 44-57. Pulkkinen, L., & Pitkanen, T. (1994). A prospective study of the precursors to problem drinking in young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 55, 578–587. Ramskogler, K., Hartling, I., Riegler, A., Semler, B., Zoghlami, A., Walter, H., et al. (2001). Possible interactions between alcohol and other drugs and their relevance in the pharmacological treatment of the elderly. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift, 113, 363–370. Ragland, D. R., Greiner, B. A., Yen, I. H., & Fisher, J. M. (2000). Occupational stress factors and alcohol-related behavior in urban transit operators. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 24, 1011–1019. Regev, A., & Jeffers, L. J. (1999). Hepatitis C and alcohol. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 23, 1543–1551. Salome, H. J., French, M. T., Matzger, H., & Weisner, C. (2005). Alcohol consumption, risk of injury, and high-cost medical care. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research, 32, 368–380. Sawchuk, C. N., Roy-Byrne, P., Goldberg, J., Manson, S., Noonan C, Beals, J., et al. (2005). The relationship between post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and cardiovascular disease in an American Indian tribe. Psychological Medicine, 35, 1785–1794. Sayette, M. A. (1999). Does drinking reduce stress? Alcohol Research and Health, 23, 250–255. Schubiner, H. (2005). Substance abuse in patients with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: Therapeutic implications. CNS Drugs, 19, 643–655. Schuckit, M. A., & Smith, T. L. (2001). Comparison of correlates of DSM-IV alcohol abuse or dependence among more than 400 sons of alcoholics and controls. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 25, 1–8. Schuckit, M. A., Smith, T. L., Kalmijn, J., Tsuang, J., Hesselbrock, V., & Bucholz, K. (2000). Response to alcohol in daughters of alcoholics: A pilot study and a comparison with sons of alcoholics. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 35, 242–248. Scott, R. B. (1989). Alcohol effects in the elderly. Comprehensive Therapy, 15, 8–12. Sher, L., Oquendo, M. A., Conason, A. H., Brent, D. A., Grunebaum, M. F., Zalsman, G., et al. (2005). Clinical features of depressed patients with or without a family history of alcoholism. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 112, 266–271. Smith, M. (1986). Genetics of human alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenases. In Advances in Human Genetics (Vol. 15, pp. 249–290). New York: Plenum Press. Soloff, P. H., Lynch, K. G., & Moss, H. B. (2000). Serotonin, impulsivity, and alcohol use disorders in the older adolescent: A psychobiological study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 24, 1609–1619. Sommer, W. H., Arlinde, C., & Heilig, M. (2005). The search for candidate genes of alcoholism: Evidence from expression profiling studies. Addiction Biology, 10, 71–79. 8-10 Updated: January 2006 Available at: www.icap.org Sougioultzis, S., Dalakas, E., Hayes, P. C., & Plevris, J. N. (2005). Alcoholic hepatitis: From pathogenesis to treatment. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 21, 1337–1346. Spear, L. P. (2004). Biomedical aspects of underage drinking. In What drives underage drinking? An international analysis (pp. 25–38). Washington, DC: International Center for Alcohol Polices. Sternbach, H., & State, R. (1997). Antibiotics: Neuropsychiatric effects and psychotropic interactions. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 5, 214–226. Subramanian, S. V., Nandy, S., Irving, M., Gordon, D., & Smith, G. D. (2005). Role of socioeconomic markers and state prohibition policy in predicting alcohol consumption among men and women in India: A multilevel statistical analysis. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 83, 829–836. Thomson, A. D., & Cook, C. C. (2000). Putting thiamine in beer: Comments on Truswell's editorial. Addiction, 95, 1866–1868. Wakim-Fleming, J., & Mullen, K. D. (2005). Long-term management of alcoholic liver disease. Clinical Liver Disease, 9, 135–149. Wall, T. L., & Ehlers, C. L. (1995). Acute effects of alcohol on P300 in Asians with different ALDH2 genotypes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 19, 617–622. Wall, T. L., Horn, S. M., Johnson, M. L., Smith, T. L., & Carr, L. G. (2000). Hangover symptoms in Asian Americans with variations in the aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH2) gene. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 61, 13–17. Warner, L. A., & White, H. R. (2003). Longitudinal effects of age at onset and first drinking situations on problem drinking. Substance Use and Misuse, 38, 1983–2016. Weathermon, R., & Crabb, D. W. (1999). Alcohol and medication interactions. Alcohol Research and Health, 23(1). Wilens, T. E. (1998). AOD use and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Alcohol Health and Research World, 22, 127–130. Willner, I. R., & Reuben, A. (2005). Alcohol and the liver. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology, 21, 323–330. 8-11 Updated: January 2006 Available at: www.icap.org