Octavia Bryant-Stephens, Family Life, and Death in Northern Florida

advertisement

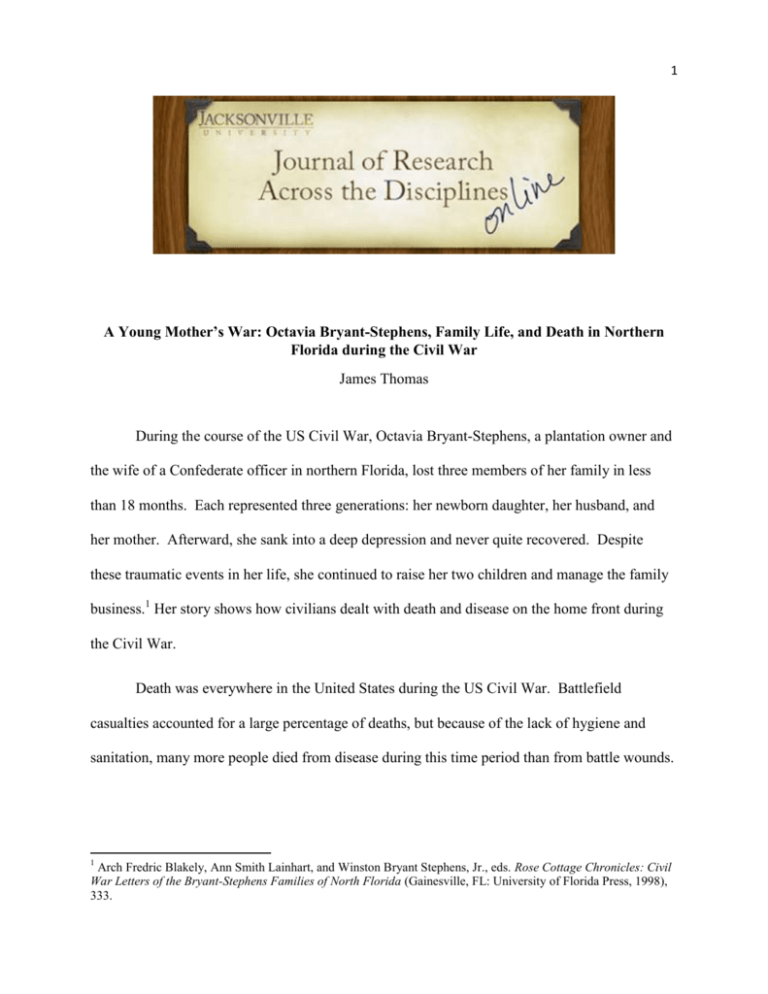

1 A Young Mother’s War: Octavia Bryant-Stephens, Family Life, and Death in Northern Florida during the Civil War James Thomas During the course of the US Civil War, Octavia Bryant-Stephens, a plantation owner and the wife of a Confederate officer in northern Florida, lost three members of her family in less than 18 months. Each represented three generations: her newborn daughter, her husband, and her mother. Afterward, she sank into a deep depression and never quite recovered. Despite these traumatic events in her life, she continued to raise her two children and manage the family business.1 Her story shows how civilians dealt with death and disease on the home front during the Civil War. Death was everywhere in the United States during the US Civil War. Battlefield casualties accounted for a large percentage of deaths, but because of the lack of hygiene and sanitation, many more people died from disease during this time period than from battle wounds. 1 Arch Fredric Blakely, Ann Smith Lainhart, and Winston Bryant Stephens, Jr., eds. Rose Cottage Chronicles: Civil War Letters of the Bryant-Stephens Families of North Florida (Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press, 1998), 333. 2 This was due to the lack of sanitation practices and inferior medical knowledge of the era.2 Death and disease was not just limited to the battlefield and the front lines of the war, but as the story of Octavia Bryant-Stephens shows, it also touched the home front. Families had to cope with the reality and the sight of their own family members dying. One recent study by Drew Gilpin Faust, titled This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War, details how families and soldiers had come to grips with the thought of dying at any moment and how they managed the large number of corpses the war produced. She argues that before the war, much of the US public believed in the notion of a “good death”, whereby one would die performing one‟s military duty and then receive a proper burial with a church service.3 However, the large number of deaths during the Civil War overwhelmed the public. Impromptu burial services had to suffice, including burial in mass graves without a proper service. In addition, the war took its toll on families, which had to cope with the deaths and the possibility of their loved ones dying. According to Gilpin Faust, mounting losses during the Civil War helped shape the modern America we know today. This paper applies Gilpin Faust‟s observations to the experiences of Octavia Stephens. In examining Octavia‟s life, scholars, such as Ellen Hodges and Stephen Kerber, have mainly portrayed her as a young mother and wife thrust into the role of plantation manager and forced to cope with the anxiety of Winston‟s militia duty and the chaos of the war going on near her home.4 No one has examined her reaction to the tragic personal losses that she experienced during the Civil War. The primary sources I will be using for this research will be published 2 Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering; Death and the American Civil War. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008), 4. 3 Ibid, 6-7. 4 Ellen Hodges and Stephen Kerber, “Children of Honor: Civil War Letters of Winston and Octavia Stephens, 18611862.” Florida Historical Quarterly 56 no.1 (July 1977) 45-74; Ellen Hodges and Stephen Kerber, “Rogues and Black-Hearted Scamps: Civil War Letters of Winston and Octavia Stephens, 1862-1863.” Florida Historical Quarterly 56, no.4 (April 1978) 54-82. 3 diary entries and correspondence between Octavia Bryant-Stephens and members of her family. During the early nineteenth century, these women were often taught to write about virtuous topics, such as morals and not of political ideals. However, Bryant-Stephens‟s letters and diary entries often violated this norm. Her writings reveal how she was able to keep her family together and maintain the plantation while her husband, Winston Stephens, was fighting for the South in the Civil War. Examining this correspondence allows us to break out of the “tunnel vision” that tends to focus on more of men‟s accomplishments in the historiography of the Civil War. In addition, an examination of Bryant-Stephens‟s letters provides us an understanding of the daily life and daily struggles of a southern woman and her family during the course of the war, particular how she coped with the deaths of loved ones. This paper include discussion of what life was like for a young mother and plantation manager living in north Florida during the Civil War and the particular challenges she faced there, including the hot climate and increased chances of contracting diseases, such as malaria. The life of Octavia Louise “Tivie” Bryant-Stephens resembled many southern slave holding women during our nation‟s greatest crisis. She was born into a southern family in 1841 but in Boston, Massachusetts, while her parents were on a family trip to see relatives.5 Shortly after she was born, her family moved to northern Florida where her family set up a plantation in Weleka, Florida. Octavia had fond memories of her childhood: I rolled my hoop on a (sic) abutment along the river edge…when [there were] only two or three wharves there. Once after a storm the water rose nearly a block not far from the gate of Mr. Reeds house (and ours across the street), and Lou Reed and I rowed a boat across 5 Blakely, Lainhart, Stephens, 9. 4 Bay Street from Mr. Reed‟s store to a Mr. Kiel‟s. Also played ball with my brothers moonlight nights on sawdust down the middle of the street, two or three girls with us.6 Octavia was raised within the same context of customs and traditions that had been taught to women all over the antebellum US South during the early nineteenth century. Women were expected to serve as managers of hearth and home. Recent studies of middling and elite southern women have provided a great deal of insight into their daily lives. Scholars, such as Eugene Genovese and Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, have confirmed that southern women were taught that their place was to take care of the house and raise children.7 This ideal was very much the core principle that was taught through not only the woman‟s family but also her religious leaders and politicians as well. One relationship that was particularly stressed was that between mother and daughter. Mothers were instructed to teach their daughters how to be successful wives and mothers and that marriage was an integral part of an adult woman‟s life.8 Anyone straying from this concept was seen as a deviant and a potential problem for society9. After a long courtship, Octavia Bryant eventually married Winston JT Stephens. Their relationship started off innocently when they first met in 1855. Her father, however, was very adamant that she could not get engaged or marry until she reached the age of eighteen because of 6 Ibid. Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, “Family and Female Identity in the Antebellum South: Sarah Gayle and her Family”, in In Joy and Sorrow: Women, Family, and Marriage in the Victorian South, 1830-1900, ed. Carol Blesser ( New York: Oxford University Press) 15-31; Eugene Genovese, “ Our Family, White and Black: Family and Household in the Southern Slaveholders‟ World View”, in In Joy and Sorrow: Women, Family, and Marriage in the Victorian South, 1830-1900, ed. Carol Blesser ( New York: Oxford University Press) 69-87.; Eugene Genovese, “ Toward a Kinder and Gentler America: The Southern Lady in the Greeting of the Politics of the Old South”, in In Joy and Sorrow: Women, Family, and Marriage in the Victorian South, 1830-1900, ed. Carol Blesser ( New York: Oxford University Press) 125-134. 8 Fox-Genovese, 19. 9 Victoria Bynum, The Long Shadow of the Civil War : Southern Dissent and Its Legacies (Raleigh, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 40, accessed December 9, 2013, http://web.ebscohost.com.ju.idm.oclc.org/ehost/ebookviewer/ebook/bmxlYmtfXzMxNTU2M19fQU41?sid=f80548 07-b396-4d53-8e6c-bafdc2147aa3@sessionmgr4004&vid=1&format=EB&lpid=lp_15&rid=0 7 5 her family‟s strict religion and moral standings. In 1856, Octavia went back to Boston to help manage her uncle‟s school.10 This was done to help her get an education as well as keep her and Winston apart, so that she could think about her future plans. Between December 5, 1856 and January 27, 1858, no record exists of Winston communicating with Octavia, but she did keep a diary, which provides a way to help us understand her mindset at the time.11 When Octavia returned to Weleka in 1858, her relationship with Winston grew stronger, and they continued to exchange romantic letters and dated for a time. Her parents, however, were still not going back on their word that Octavia could only be engaged and marry Winston when she turned eighteen. This was because of their moral and religious background, not because they didn‟t admire Winston a great deal. Their relationship hit a rocky point in early 1859 when Winston became frustrated with waiting for their engagement. However, in late October 1859, Octavia finally received her father‟s permission, and on November 1, 1859, she and Winston became husband and wife.12 Shortly after their marriage, Octavia and Winston moved to their newly established Weleka home, known as the Rose Cottage. While the exact dimensions of the house are unknown, it was smaller than Octavia‟s parents‟ house, known as the White Cottage, just a few miles away.13 Rose Cottage was also far away from the St. Johns River and out of sight from the river itself. Here, Octavia established what would be her home and her family‟s headquarters until 1863. The property itself was roughly 320 acres (which included 60 additional acres that Octavia herself bought), and Winston worked in the fields with his slaves (typical of yeoman 10 Blakely, Lainhart, Stephens Chronicles, 30. Ibid, 31. 12 Ibid, 49. 13 Ibid, 51. 11 6 farmers) and usually planted short-staple cotton, the cash crop of the day.14 During this time, he also instructed Octavia on the basics of how to manage a plantation and what tasks each slave should perform. This knowledge would be vital when Octavia had to single-handedly manage the plantation when Winston joined the southern militia. In March 1860, Octavia gave birth to a girl, Rosalie “Rosa” Bryant Stephens. She did not keep records of her well-being because she was taught that was not polite for women to do so.15 Rosa was the centerpiece of Octavia‟s family throughout the war, and her childhood was representative of how children were raised during the Civil War by Octavia recording how Rosa lived out her first years of life. When Abraham Lincoln was elected president, the southern states felt that its institutions were being threatened and decided to secede from the Union (Florida did so in February 1861). This not only divided the nation but also families. Most of Octavia‟s family, as southern slaveholders, sided with the secessionists, but her father, James Bryant, remained loyal to the Union.16 This often caused tension between her and her parents. Octavia and Winston themselves were hardly affected by the political strife although they tended to discuss secession and sectional issues with their neighbors. After Florida seceded and Fort Sumter was fired upon, Octavia‟s brother, Willie, immediately joined the Confederate army while her father fled to Cuba. Octavia was displeased with how the war had divided her family. When she saw some of her family members training for battle on the parade grounds near the Duval County Courthouse, she stated that “I declare it made me feel dreadfully to think what they are drilling for. You know how glad I feel when I think that you are not in any company, and I hope and pray you may 14 Blakely, Lainhart, Stephens Chronicles, 22-23. Ibid, 7. 16 Ibid, 58. 15 7 never be in any”.17 Unfortunately for Octavia, Winston himself joined a southern militia unit based in Fernandina Beach. In fall 1861, Winston Stephens left his family to serve in the Confederate militia based in Florida. Octavia assumed the role of not only a mother and wife but also a plantation manager, something she had never experienced before. During the Civil War, southern women, like Octavia, were not only housekeepers and child bearers. They were often put in dangerous situations as the war raged close to home and their loved ones were sent off to fight and die. They took on new roles, such as shop owners and plantation heads, with little or no experience. These circumstances would help transform the role of women from simply housekeepers to important and integral parts of southern society. Scholars, such as George Rable and Drew Gilpin Faust, have argued that women played a very vital role in keeping southern ideals alive throughout the antebellum and Civil War eras.18 Women of powerful men also served as aides and advisors, which often put them in a position of power equal to or even greater than their male counterparts. One notable example of this was Mary Dorsey Henry, the granddaughter of John Calhoun, who wanted to pursue politics in Washington despite objections from conventional society.19 Also, there was Sarah Dawson, who actually wanted to join in the fighting for the South. As historians have shown, southern women played a very important role in not only in raising children but also aiding the southern home front. 17 Tracy Revels, “Grander in Her Daughters: Florida‟s Women during the Civil War”. (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press 2004) 39. 18 George Rabel, “Missing in Action: Women of the Confederacy”, in Divided Houses: Gender and the Civil War, eds. Catherine Clinton and Nina Silber (New York: Oxford University Press) 134-146; Drew Gilpin Faust, “Altars of Sacrifice: Confederate Women and the Narratives of War” in Divided Houses: Gender and the Civil War, eds. Catherine Clinton and Nina Silber (New York: Oxford University Press) 171-199. 19 Faust, 185. 8 Octavia was left to manage slaves. Winston had acquired a few slaves, including Burrell, Georgie, Hattie, and about ten others.20 Their jobs ranged from clearing the fields to spinning yarn and planting crops. Winston left Octavia instructions via letters in how to go about managing the slaves including punishment if they became insubordinate. This included permission to whip the slaves, if necessary. One slave, Georgie, was particularly troublesome at times and often asserted that he was not afraid of Octavia.21 To help her with her new duties, Octavia‟s mother, Rebecca Bryant, came to stay with her and her family. This caused some complaining among the slaves. One argued that this meant that they had “two bosses and extra work”.22 Another complaint the slaves had was that their diet of potatoes and pork gave them heartburn. Still, Octavia had managed to organize the work so that the gardens were planted and fields cleared in time for the annual harvest. By late 1861, there were not many pitched battles in north Florida, and Octavia and Winston were able to communicate frequently. Winston did not fight in any major engagements. He performed picket duty on several occasions and often wrote to Octavia. For example, a letter dated September 7, 1861 stated that Octavia wanted to join up with Winston near Jacksonville, but his duties prevented that from happening.23 Winston sometimes made visits during his early years in the militia, and Rosa never forgot to say “Pa Pa”. Octavia recorded in her diary that just like her mother, she missed him when he wasn‟t around. Rosa herself was described by her mother as being “hardheaded” and at times mischievous.24 Nevertheless, she would help keep Octavia‟s mind off of missing her husband and his military duties. After stopping by for a visit 20 Revels, 93. Ibid, 67. 22 Ibid, 100. 23 Blakely, Lainhart, Stephens, 65. 24 Revels, 49. 21 9 in November, Winston departed for Palatka to perform his duties for the militia. Rosa began to teethe and learn how to speak, but during this time, she suffered from persistent fevers. Octavia‟s life changed dramatically in early 1862. Union forces were aggressively moving on Jacksonville. Winston was worried for his wife and child, and Octavia re-assured him that she would take Rosa and seek cover in the neighboring woods if Union soldiers ever came close. At the end of January 1862, Winston arrived home and replenished the plantation‟s food supply, but he had to depart soon afterwards. During this time, Octavia constantly worried that the war would be fought close to her home. Throughout 1862, many gunboat skirmishes occurred as northern troops fought against southern beach defenses. Octavia often heard many of these engagements, and this made her fear for Winston‟s safety, as she had expressed in many of her letters to him.25 Her fears were realized when in February, the Union army established itself in Jacksonville and later moved on Lake City. Winston‟s company was among the Confederates who fought the Union advance at the Battle of Olustee with much success. Octavia was happy to hear about her husband‟s victory and also that his company had suffered no casualties. However, all was not well as her mother was extremely ill with what was described as “congestion of the brain”.26 During that year, Octavia‟s letters were filled with discussions about the health of family members and slaves. Fever was a constant threat.27 North Florida‟s muggy climate made heat illnesses ever more commonplace and worse yet were the constant threat of mosquito-borne diseases, such as malaria and yellow fever. These illnesses plagued not only soldiers fighting in the area but also people living in this part of Florida. Octavia struggled to tend to sick family 25 Ibid, 116. Ibid, 325. 27 Ibid, 116. 26 10 members as well as slaves as some (and sometimes most) were usually sick with fever, possibly caused by malaria-infected mosquitos.28 She would, at times, have to tend to more than one slave suffering from illness. Some illnesses were heat-related, such as dehydration and heat stroke from working the fields all day in the hot Florida climate. Under her care, Octavia‟s slaves recovered from their illnesses and were able to harvest almost 200 pounds of cotton for sale.29 She also managed to replenish the pork supply by slaughtering the sows. By the end of 1862, she and others in the house, including Rosa, contracted various health problems, including fever. In January 1863, Octavia experienced her first death in the family. The couple‟s youngest daughter, Isabella, fell very ill with a bad rash and fever, which most likely may have been scarlet fever.30 She died at the end of January, and this deeply affected the family.31 Octavia personally experienced multiple bouts of depression, and Winston found himself also mourning heavily due not just to the fact that his newborn daughter had just died, but he could not be with his family at the time. Unfortunately, child mortality rates were higher during the nineteenth century and especially during the Civil War due to lack of medical knowledge for neonatal care.32 During the height of the war in 1863, Winston‟s letters arrived less frequently, and this caused concern among the family. In mid-March, Octavia and Rosa went to see Winston in Jacksonville near where he was stationed. She was especially worried about AfricanAmerican regiments possibly coming to Jacksonville and Weleka. 28 Faust, 136. Blakely, Lainhart, Stephens, 145. 30 WebMD, “Understanding Scarlet Fever: The Basics,” Scarlet Fever Home, March 30, 2013, accessed November 17, 2013, http://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/understanding-scarlet-fever-basics 31 Revels, 53. 32 Suzanne Lebsock, The Free Women of Petersburg: Status and Culture in a Southern Town, 1784-1860. (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1984), 160. 29 11 In May 1863, disease threatened Rosa‟s life. She had developed a bad case of whooping cough that persisted for several weeks as well as a fever that Octavia treated with Caster Oil, a popular remedy for the time.33 This weighed heavily on Octavia, and in her letters to Winston, she reported that her daughter‟s cough would not stop. She was worried that she, like Isabella, would die from her illness.34 By the end of July, possibly hearing about the events of Gettysburg and Vicksburg, she believed that the Confederacy was in trouble. This was a view probably held by many southerners at the time.35 When Octavia was preparing for a trip to Baldwin to see Winston in early August, she was worried about how the slaves were mismanaging the corn and the passing Union army. In mid-August, Octavia became pregnant for a third time. In October 1863, Octavia arrived in Baldwin to see Winston. They spent much time together, and she was able to celebrate her 22nd birthday with him. Later that month, she and her family left for Thomasville, Georgia in order to escape the federal army. When they arrived, Octavia looked for a house for her and Winston because she did not believe they would return to Florida after the war (probably because of Unionist support in the area).36 She lost her dream house after the payment negotiations went awry (a southern woman making a business deal without her husband was taboo in the nineteenth century)37, but she eventually found a suitable home for her family in January 1864. During this time, she sold her family‟s wagon and some corn to afford a $30 pig promised to her by a relative.38 She also hired out many of her slaves, which was a common practice among slave owners to raise revenue. 33 Blakely, Lainhart, Stephens, 232. Ibid, 233. 35 Ellen Hodges and Stephen Kerber, “Rogues and Black-Hearted Scamps: Civil War Letters of Winston and Octavia Stephens, 1862-1863." Florida Historical Quarterly 56, no.4 (April 1978) 55. 36 Blakely, Lainhart, Stephens, 294. 37 Lebsock, 56. 38 Blakely, Lainhart, Stephens, 303. 34 12 In the middle of these constant changes in her life, tragedy again struck Octavia‟s family. First, on March 1, 1864, during a small skirmish, Winston was killed. He and his company were fighting a small detachment of Union gunboats when shrapnel from cannon fire fatally hit him, and he passed away on the field. When Octavia received the news, she was utterly devastated by these tragic events, maybe even more so then when Isabella died, and went into deep mourning for days at a time which included crying spells and other bouts of sadness. Also, she mostly became a recluse afterwards, rarely leaving the house and tending to her ill mother.39 A few days later, her mother succumbed to her brain illness and died.40 Octavia was stricken to the core with sadness over the whole situation. She wrote a grim summary of how southern women dealt with their grief in hard times: With a sad, sad heart I began another journal. On Sunday Feb 28th, dear Mother was taken with a congestive chill. On Friday March 4th, Davis came with the news of the death of my dear dear husband, he was killed in battle near Jacksonville on the 1st of March. Mother grew worse and on Sunday, Mar 6th, she too was taken from us, between 12 and 1o‟clk (sic) she passed quietly away from Typhoid Pneumonia. At 7 o‟clk (sic) p.m. I gave birth to a dear little baby boy, which although three or four weeks before the time, the Lord still spares to me. Mother was buried on the 7th, and Rosa was taken with fever, but recovered after two days. I have named my baby Winston, the sweet name of that dear lost one my husband, almost my life. God grant that his son whom he longed for but was not spared to see may be like him. I now begin as it were a new life and I pray that the Lord will be strength to bear up under the great affliction, and with His help and the examples of those two dear ones now with him I may be enabled to do my duty in this life and be prepared when the Lord calls to meet them in that „better world‟ when there will be more parting and no more sorrow.41 Octavia described her mother‟s illness as typhoid pneumonia, which would have meant her mother probably died from a bacterial infection in her lungs. However, this diagnosis is most 39 Ibid, 328. (This could have been either meningitis, which is can be caused by Streptococcus bacteria, or another related brain illness.)WebMD, “Brain Diseases,” Brain and Nervous System Health Center, October 25,2012, accessed November 17, 2013, http://www.webmd.com/brain/brain-diseases 41 Daniel Schafer, “Thunder on the River: The Civil War in Northeast Florida”. (Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press) 303. 40 13 likely mistaken because typhoid is caused by salmonella bacteria, which is associated with food poisoning.42 After the deaths of her mother and husband, Octavia went into a deep depression, which lasted for several weeks. It was not until the end of March that she finally emerged from her house. However, her grief was very much noticeable, and she continued to suffer bouts of depression until the end of the war.43 One way that she coped was by focusing on raising her two children, Rosa and Winnie and making sure she lived for their sake.44 Other ways that she coped included taking care of the family slaves, who were still ill day after day. These things helped keep her mind off her losses and helped her manage her day-to-day existence. She wrote that Rosa and Winnie were her new primary focus in life.45 They lived out the war‟s end in Thomasville and returned to Weleka in 1868 to start over in the aftermath of war and emancipation. Octavia Bryant-Stephens‟s story shows that women were not only mothers and house managers, but they were a driving force behind maintaining the southern home front while constantly dealing with death caused by war and disease. Octavia‟s life had taken many tragic turns. From her beginnings as a southern woman marrying a yeoman farmer to being a wife and plantation mother while her husband was away, she endured great hardships from illnesses to plantation issues such as managing slaves to finally the death of a child, her husband, and her mother. She emerged from this forever a changed woman. Her endurance has left her able to 42 WebMD, “Typhoid Fever,” Information and Resources, May 30,2012, accessed November 25, 2013, http://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/typhoid-fever 43 Blakely, Lainhart, Stephens, 332. 44 Ibid, 334. 45 Blakely, Lainhart, Stephens, 335. 14 cope with whatever comes next for her and her children. Like many southern women, Octavia Stephens was fighting her own battles on the home front. Bibliography Blakely, Arch F., Ann Lainhart, Winston B. Stephens Jr., Rose Cottage Chronicles: Civil War Letters of the Bryant-Stephens Families of North Florida. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 1998. Bynum, Victoria E., The Long Shadow of the Civil War : Southern Dissent and Its Legacies. Raleigh, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2010. Accessed December 9, 2013. http://web.ebscohost.com.ju.idm.oclc.org/ehost/ebookviewer/ebook/bmxlYmtfXzMxNTU2M19f QU41?sid=f8054807-b396-4d53-8e6cbafdc2147aa3@sessionmgr4004&vid=1&format=EB&lpid=lp_15&rid=0 Faust, Drew Gilpin. "Altars of Sacrifice: Confederate Women and the Narratives of War." In Divided Houses: Gender and the Civil War, by Catherine Clinton and Nina Silber, 171-199. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992 Faust, Drew Gilpin. This Republic Of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008. Fox-Genovese, Elizabeth. “Family and Female Identity in the Antebellum South: Sarah Gayle and Her Family”. In In Joy and Sorrow:Women, Family, and Marriage in the Victorian South, by Carol Blesser, 15-31. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991. Genovese, Eugene. “Our Family, White and Black: Family and Household in the Southern Slaveholders‟ World View”. In Joy and Sorrow:Women, Family, and Marriage in the Victorian South, by Carol Blesser, 69-87. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991 15 ----. “ Toward a Kinder and Gentler America: The Southern Lady in the Greeting of the Politics of the Old South”. In In Joy and Sorrow:Women, Family, and Marriage in the Victorian South, by Carol Blesser, 125-134. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991. Hodges, Ellen, Kerber, Stephen. "Children of Honor: Civil War Letters of Winston and Octavia Stephens, 1861-1862." Florida Historical Quarterly 56, no.1 (July 1977) 45-74. Hodges, Ellen, Kerber, Stephen. "Rogues and Black-Hearted Scamps: Civil War Letters of Winston and Octavia Stephens, 1862-1863." Florida Historical Quarterly 56, no.4 (April 1978) 54-82. Lebsock, Suzanne. The Free Women of Petersburg: Status and Culture in a Southern Town. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1984. Marlen, James. The Children’s Civil War. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1998. Martin, Richard, and Daniel Schafer. Jacksonville's Ordeal by Fire. Jacksonville, FL: Florida Publishing Company, 1984. Rable, George. ""Missing in Action": Women of the Confederacy." In Divided Houses: Gender and the Civil War, by Catherine Clinton and Nina Silber, 134-146. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992. Rable, George A. Civil Wars: Women and the Crisis of Southern Nationalism. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1991. Revels, Tracy J. Grander in her Daughters: Florida's Women during the Civil War. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 2004 Schafer, Daniel. Thunder on the River: The Civil War in Northeast Florida. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press, 2010. Stephens, Octavia. "Letter from Octavia Bryant Stephens to Winston J.T. Stephens, August 30, 1861." University of Florida Digital Collections, 1861. Accessed July 23, 2013. http://ufdc.ufl.edu/AA00008789/00001/1j?search=stephens-bryant. United States Government. "Original Return of the Eighth Census." United States Department of Agriculture census, 1864. Accessed July 23, 2013. http://www.agcensus.usda.gov/Publications/Historical_Publications/1860/1860b-01.pdf. WebMD. “Brain Diseases.” Brain and Nervous System Health Center. Last modified October 25, 2012. Accessed November 17, 2013. http://www.webmd.com/brain/brain-diseases ---. “Understanding Scarlet Fever: The Basics.” Scarlet Fever Home. Last modified March 30, 2013. Accessed November 17, 2013. http://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/understanding-scarlet-feverbasics ---. “Typhoid Fever.” Information and Resourcs. Last modified May 20, 2012. Accessed November 25, 2013. http://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/typhoid-fever 16