Thirsty Interdialytic Weight Gain and Thirst-Interventions in

advertisement

Mistiaen, P. Thirst, interdialytic weight gain, and thirst interventions in hemodialysis patients: a literature

review. Nephrology Nursing Journal: 2001, 28(6), 601-604, 610-615

Postprint Version

1.0

Journal website

http://connection.ebscohost.com/content/article/1020332237.html

Pubmed link

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12143470

DOI

This is a NIVEL certified Post Print, more info at http://www.nivel.eu

Thirsty Interdialytic Weight Gain and Thirst-Interventions

in Hemodialysis Patients: A Literature Review

PATRIEK MISTIAEN

Noncompliance is a common problem in hemodialysis (HD) patients (Christensen, Benotsch, & Smith,

1997).

Patients are asked to comply with medical advice that may disturb their normal routine. In addition to the

dialysis sessions two to three times a week for many years, patients have to take many medications

and adhere to diet and strict fluid intake restrictions. Noncompliance is found in all aspects (Leggat et al.,

1998), but adhering to the fluid restriction is the most difficult aspect for most patients (Baldree, Murphy, &

Powers,, 1982; Goverde & Grypdonck, 1998).

Noncompliance with fluid restriction may cause a large interdialytic weight gain (IWG) and may lead

to chronic fluid overload, resulting in a much greater risk for cardiovascular comorbidity and mortality

(Abuleo, 1998; Leggat et al., 1998). Depending on the definition, excessive weight gain occurs in 10"/i)

{Leggat et al., 1998) to 9m) {Lin & Uang, 1997) of all dialysis patients.

One obvious reason for drinking too much and excessive IWG might be that these patients suffer

from thirst as demonstrated by quotes from the literature, such as ".,.many hemodialysis patients complain

of compulsive thirst, which causes an exaggerated ingestion of fluids and this in turn may lead to chronic

fluid overload..." {Graziani et al., 1993) or "....They explain that they do not comply because of intolerable

thirst and even those who do comply usually also complain of thirst. TTiey com- plain bitterly of thirst

although they are often overhydrated." (De Nour & Czaczkes, 1980).

However, thirst is a difficult area to research due to its subjective nature.

Moreover, many physiological, psychological, and social variables influence the thirst sensation. In

addition, the drinking reaction to thirst is influenced by many of these factors. Like pain, thirst is a

subjective feeling that exists when a person says it exists, and can not be measured other than by asking

people. However, in contrast to pain, which is generally considered as a burden, thirst is seen as a

normal signal without the negative connotation of burden.

Goal: To summarize the findings in the literature concerning thirst, interdialytic weight gain and thrist

interventions in hemodialysis patients.

Objectives: 1. Identify why thirst is a difficult concept to measure and study.

2. Describe the relationship between thirst and interdialytic weight gain in hemodialysis patients.

3. Discuss the three interventions presented to treat thirst in the hemodialysis population.

One of the tasks of nephrology nurses is counseling patients and helping them cope with their

regimens, especially the fluid restriction.

It would be very helpful for nurses to know how many HD patients suffer from thirst and how to prevent

or treat thirst. Therefore, a literature search was performed to review the body of knowledge on thirst in

HD patients and to address the following questions; (a) What is the prevalence of thirst (how many HD

patients have thirst)? (b) To what extent is thirst related to IWG? and (c) What interventions are applied to

minimize thirst?

This is a NIVEL certified Post Print, more info at http://www.nivel.eu

Mistiaen, P. Thirst, interdialytic weight gain, and thirst interventions in hemodialysis patients: a literature

review. Nephrology Nursing Journal: 2001, 28(6), 601-604, 610-615

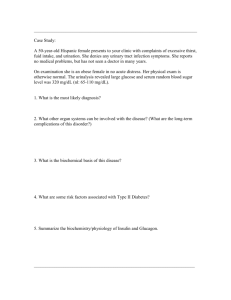

METHODS

A search was made using several electronic literature databases (MEDUNE, CINAHL, EMBASE,

PSYCHFIRST, SCI) with the keywords "thirst and hemodialysis." In addition, a free-text search with

"thirst" and a retrograde search were made via references from the articles that were already identified. All

searches were done in the second half of December 1999. The literature search was hmited to articles

published in journals between 1980 and 1999 in the English, Dutch, German, or French language.

Furthermore, articles had to describe empirical research on HD patients and thirst had to be explicitly

measured.

The search with the keywords "thirst and hemodialysis" in MEDLINE, EMBASE, and SCI resulted in the

identification of 18, 9, and 25 studies, respectively. No articles were found in the databases CINAHL

and PSYCHFIRST The overlap between MEDUNE and EMBASE was three references, between

MEDLINE and SCI seven references, and between EMBASE and SCI five references.

Three references appeared in all 3 databases. This initial search resulted in a total of 40 articles. After

reading the articles, 22 were excluded for the following reasons: the study was a review (n = 1); thirst was

not measured as a variable (n — 13); the article was a conference abstract [n = 2); the article was not

research [n = 2); the article did not concem HD patients [n

— 4), Additional searches produced five complementary articles. A total of 23 studies were eligible for

analysis.

The studies were published in 19 different journals and originated from 12 different countries. In some

studies, thirst was the main focus, and in others, it was measured together with several other variables.

Sample characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Sample sizes varied from 5 to 247 patients (mean = 39.6; median = 22).

There was a large variety between samples with regard to patient characteristics (such as age, time on

HD, comorbidity, etc.) and the sampling method. Also, many studies lacked important information on

factors that may influence the thirst-feeling.

Therefore, all comparisons between studies have to be interpreted with caution. Nine studies gave

information about the prevalence of thirst.

Prevalence is defined as how many patients have a certain condition (thirst) at a certain moment in

time (Bowling, 1997). Six studies gave information about the relationship between thirst and IWG, and 15

articles reported about some kind of intervention.

RESULTS

WHAT IS THE PREVALENCE OF

thirst? Thirst was measured in many different ways with regard to both the format of the questions and

the answer options. For example, in one study patients were asked, "Are you thirsty?" in another, the

question was "How thirsty are you?" and in yet another, "To what extent are you bothered by excessive

thirst?' Answer categories varied from a dichotomous yes/no answer over 5-point answer categories to

continuous visual analogue scales (VAS). For the sake of comparison, in the two studies (Heidbreder et al.,

1990; Wirth & Folstein, 1982) in which VAS scores were used with only anchors at the extremes,

frequencies were calculated from the figures given by the authors, and the VAS scale was divided into four

categories. However, much more problematic to compare numbers of the different studies was the

great diversity in time-frames, varying from thirst right now to thirst in the previous 2 months; four studies

did not mention a time frame. Moreover, comparison of the studies was difficult because the samples

differed a lot in patient characteristics that can influence thirst symptoms. Only baseline measurements

from the intervention studies were included. An overview is presented in Table 2.

When taking the limitations into consideration, the prevalence of thirst varied fi-om 6% (Eevin &

Goldstein, 199(i) to 95'yo (Dominic, Ramachandran, Somiah, Mani, & Dominic, 1996). However, these

extremes were found in small and selective study populations. The most representative studies were those

of Giovannetd et al. (1994) and Virga et al.

(1998). The sample in Giovannetti's study was relatively large (n = 247) and comprised of compliant

(according to the authors) patients from five different centers, with no diabetic patients. In the sample in

Virga's study, all patients were from one center {n— 73), and there was very little nonresponse. Both

studies reported comparable percentages of patients with low thirst scores (14"/o not abnormally thirsty and

This is a NIVEL certified Post Print, more info at http://www.nivel.eu

Mistiaen, P. Thirst, interdialytic weight gain, and thirst interventions in hemodialysis patients: a literature

review. Nephrology Nursing Journal: 2001, 28(6), 601-604, 610-615

15 % never thirsty, respectively) and similar percentages of patients with high thirst scores (44"/ii with

thirst almost always present and disturbing sleeping and working and 49"/i) with thirst occurring every

day, respectively). Giovannetd's study concerned thirst in the last interdialytic period and Virga's about the

occurrence of thirst at home, (thus, not in the intradialytic period). In three studies (Bjorvell & Hylander,

1989; Hang & Clyne, 1997; Virga et al,, 1998) in which the prevalence of several symptoms

was investigated, thirst was the most common symptom. In the study of Hays, Kallich, Mapes, Coons, and

Carter (1994), thirst ranked in seventh place out of 35 symptoms, and it ranked in third place among

symptoms that caused severe distress to the patients.

[TABLE 1]

[TABLE 2]

To what extent is thirst related

to interdialytic weight gain? In the study by Giovannetti et al. (1994), exaggerated thirst was reported by 86"/o

of the patients, while IWG greater than 4"/i) of body weight was found in 34"/i) of patients. Patients with the most severe thirst

had a mean IWG of 4.1"/(j, or 2.6 kg, in contrast to 3.1"/o or 1.9 kg in patients with the lowest thirst scores. An analogous picture is

presented by Yamamoto et al. (1986), in which the patients with the most severe thirst had a mean IWG of 5.3 kg, and the patients

with no thirst or mild thirst gained 1.4 kg.

MartinezA/ea, Garcia, Gaya, Rivera, and Oliver (1992) studied the influence of a hypertonic saline-infusion on thirst in two

groups of HD patients (IWG greater than .5%:, IWG less than 3%] and one group of healthy controls. The study was done before

the dialysis session. No differences were found at baseline, but during and after the infusion, thirst scores were higher in patients

with a higher IWG. This group also needed more fluid to quench their thirst afterwards.

Wirth and Folstein (1982) studied the relationship between thirst (in the previous 2 months) and the mean IWG over

the previous ten dialysis sessions. They found a significant correlation coefficient of 0.78 in patients without kidneys

and 0.46 (but no longer significant) in patients with kidneys. Heidbreder et al. (1990) also found a positive correlation

coefficient of 0.86 between thirst, measured on a VAS at the beginning of a dialysis session, and the preceding IWG.

Moreover, patients with IWG less than 3 kg appeared to have a lower thirst score than patients with IWG of greater

than 3 kg. In contrast, Oldenburg, MacDonald, and Perkins (1988) reported a negative correlation between thirst and

drinking, and no relationship between thirst and IWG.

What interventions are applied

to minimize thirst? In the selected studies, thirst was measured as a dependent variable, but not always as the

main outcome variable. Some studies focused on hypertension, but measured thirst as a possible sideeffect.

Broadly speaking, three types of interventions could be distinguished: dialysis-technical, pharmaceutical, and

dietetic.

Dialysis-technical interventions.

The dialysis-technical interventions can be divided into two groups: frequency of dialysis and varying

the amount of dialysate sodium, which was sometimes combined with varying the ultrafiltradon rate.

The effect of daily dialysis compared to three times a week has been studied in home dialysis

patients (Kooistra, Vos, Koomans, & Vos, 1998). It was concluded that quality of life and hemodynamic

control improved with daily dialysis and that patients were less thirsty. Second, many studies have been

carried out with dialysate sodium concentration (NaJ, with both high and low sodium levels, as wel! as

many different ways of sodium profiling during dialysis.

Profiling is a method used during a dialysis session to decrease a level of a concentration of dialysate

constituents (e.g., sodium) or to decrease the ultrafiitration (UF) rate. There are three types of profiling (see

Figure 1): a linear decrease, an exponential decrease, and a stepwise decrease.

Some studies were aimed at lowering side-effects and symptoms during dialysis, such as cramps and

hypotension, and others focused more on lowering symptoms between dialysis sessions, such as

hypertension or thirst In the current review, only effects on thirst and IWG are discussed (see Table

3), Three studies (Barre, Brunelle, & Gascon-Barre, 1988; Cybulsky, Matni, & Hollomby, 1985; Daugirdas,

Al Kudsi, Ing, & Norusis, 1985) compared dialyzing at a constant high sodium level versus dialyzing with a

This is a NIVEL certified Post Print, more info at http://www.nivel.eu

Mistiaen, P. Thirst, interdialytic weight gain, and thirst interventions in hemodialysis patients: a literature

review. Nephrology Nursing Journal: 2001, 28(6), 601-604, 610-615

constant lower concentration. All found a greater IWG in the high sodium group, but were inconclusive

with regard to thirst.

Profiling sodium versus dialyzing at a constant sodium level was compared in four studies; two

(Daugirdas et al., 1985; Sang, Kovithavongs, Ulan, & Kjellstrand, 19!)7) found a greater IWG and more

thirst in the group with sodium profiling, while the other two (Parsons, Yuill, Llapitan, & Harris,

1997; Sadowski, Allred, &Jabs, 1993) found no differences between the groups.

Two studies investigated the effect of profiling the UF rate versus a constant UF rate; Ebel et al. (1997)

found no effect on thirst or IWG, and Parsons et al. (1997) reported that the patients in the control group

were more thirsty.

Finally, four studies combined sodium profiling with profiling the UF rate: Ebel et al. (1997) and Levin

and Goldstein (1996) found more thirst in the profiled group while the other two studies (Dominic et al.,

1996; Parsons et al., 1997) found the opposite. Only one study (Ebel et al., 1997) found that the IWG was

greater in the profiled group, while the other three found no difference between the groups.

[FIGURE 1]

Pharmaceutical interventions.

The pharmaceufical interventions are based on the main dipsogenic (= thirst inducing) role of

angiotensine- II, which is well known from physiological research (Fitzsimons, 1998).

Angiotensine-II is a circulating hormone that interacts on the limbic structures of the brain and causes

a thirst sensation. Angiotensine-II is mainly formed through interaction of angiotensine and renin into

angiotensine- I, which in turn reacts with angiotensine converting enzyme (ACE) and forms angiotensineII.

Experiments have been done with ACE-iniiibitors that inhibit the conversion of angiotensine-1

into angiotensine-II. An overview of the results of the ACE inhibitor experiments in HD patients is

presented in Table 4. It is important to note that the studies investigating ACEinhibitors in diaiysis patients

focused in the first instance on hypertension and not on thirst.

Studies have been done with enaiaprii (Oldenburg, MacDonaid, & Shelley, 1988), captoprii (Giovannetti

et ai., 1994; Yamamoto et ai., 1986), ciiazapril {Kuriyama, Tomonari, & Sai^ai, 1996) and

iisinoprii (Giovannetti et al., 1994). Three studies (Kuriyama et al, 1996; Oidenburg et al., 1988;

Yamamoto et al., 1986) found a decrease in thirst and IWG after administration of an ACE-inhibitor, and a

fourth study (Giovannetti et al., 1994) found no effect on thirst for either lisinoprii or captopril.

Finally, one more study should be mentioned (Rosansky, Johnson, & McConnell, l!)93) in which

transcutaneous administration of clonidine, a central alpha-2 agonist antihypertensive agent, was

investigated. No difference in thirsl was found between this method of administration and the conventional

oral method.

[TABLE 3]

[TABLE 4]

Dietetic intervention. One dietetic intervention was identified. A low-protein diet te.sted by Giovannetti et al.

(1994) was found to decrease thirst.

Discussion and Conclusions From this review it is concluded that thirst is a common and severe symptom in

dialysis patients. There is also a positive relationship between thirst and excessive IWG, meaning patients with high

thirst scores show also high IWG.

However, only a small number of relevant studies were found between 19H0 and 1999. Moreover, most studies were

difficult to ctmipare because of methodological differences, which included small, nonrepresentative samples. It was

also found that many different scales and time frames were used to measure thirst. There is also a language problem in

the interpretation of the results. Thirst is a natural phenomenon that urges people to drink - so, is it a problem area

when some patients say they "have" thirst, or is there oniy a problem when people are "troubled" with thirst? Are

the numbers of thirsty patients in the different studies comparable when so many different wordings of questions were

used? Is l^'Vo of patients having the burden of thirst more problematic than 2()"/(i of patients having thirst? It is

This is a NIVEL certified Post Print, more info at http://www.nivel.eu

Mistiaen, P. Thirst, interdialytic weight gain, and thirst interventions in hemodialysis patients: a literature

review. Nephrology Nursing Journal: 2001, 28(6), 601-604, 610-615

important to have uniform measurements of thirst, however, regardless of the way thirst is measured, all patients with

thirst have a problem, because all HD patients are not allowed to respond in a natural way to the thirst signal.

Scajcely any data were available in the time period searched on the course of thirst during the day or over the inter

and intradiaiytic periods, and no data at all was found on the course of thirst over the entire illnessperiod.

Although there is a relationship between thirst and IWG, no conclusions can be drawn on a causal relationship that

finds thirst leading to drinking, leading to large IWG. This relationship is not necessarily as linear as often thought.

For example, patients with high IWGs who do not complain of thirst may drink a lot to prevent thirst, or drink

whenever they feel slightly thirsty. It may also be that a patient feels very thirsty but has the willpower to refrain from

drinking.

Patients may be very thirsty, but still have low IWGs because they participate in sports and lose fluid by sweating.

It is difficult to compare the dialysis- technical interventions, because of the many different levels of

sodium concentrations, the various methods of profiling, and various combinations with UF profiling. Positive,

negative, and no effects on thirst have been rept)rted making conclusions difficult to draw. With regard to

the pbarmaceutical interventions with ACE-inhibitors, it was found that they have a general tendency to decrease thirst

and IWG, or at least that they cause no increase. However, no firm conclusions can be drawn because of the small

sample sizes and the lack of double-blind studies. Since only one study rept)rted on a dietetic intervention for thirst, no

conclusion can be drawn. It is amazing that the search produced no studies on the effect of low-sodium diets, since

many articles indicate that sodium intake is a major cause of thirst.

It was also surprising to find that no studies have been published on the effect of symptomatic interventions such as

ice cubes, chewing gum, distraction, etc., since these remedies are frequently discussed by patients and can be found

on internet bulletinboards.

Recently Welch and Davis (2000) reported that patients use many different strategies and., surprisingly they do not

use the strategy they consider the most effective most often.

Based on the results of this review, it is recommended that complementary literature reviews should be performed to

investigate thirst interventions in other patient categories, such as terminal patients, preoperative and postoperative

patients, or diabetics, for whom thirst is also a major problem, although thirst may be from another origin in those

patients. In this way, more potential therapeutic and symptomatic thirst intei-ventions could be identified, and

subsequently tested in HD patients.

There is also a need for more empirical research on the prevalence of thirst in HD patients and on the course of thirst

across the time-fi-ame ofa day and a week. More qualitative research is also needed to investigate how patients

experience thirst and how they cope with it.

Finally, this literature review gives an overview of studies on HD patients in which thirst was measured.

However, the practical applicability of this review is limited in view of the problem of noncompliance, which was

the starting point in the introduction.

Noncompliance is a very complex concept, with many influencing and causal factors, and there are many ways in

which to intervene.

Thirst, as a possible cause of chronic fluid-overload and excessive IWG, is just one of many possible targets

for interventions.

REFERENCES

Abuleo. J.G. (1998). Large interdialytic weight gairi.s: Causes, consequences.

and corrective measures. Seininar.s in

D(f;/v.w.v. //(I). 25-32.

Baldree. K.S.. Muiphy. S.P.. & Powers. M J.

(I9S2). Stress identification and coping patterns in patients on hemodialysis.

Niir.sinfi Researdi. 3112), 107-112.

BaiTe. P.E.. Brunelle. G.. & Giiscon-Barre.

M. (1988). A randomized double blind trial of dialysale sodiums of 145 niHq/L. 150 mEq/L. and 155 mEq/L.

ASAIO Tran.spiankilion. J-/(3), 338- 34 L Bjorvell. H.. & Hylander. B. (1989).

Funetional status and personality in patients on chronic dialysis. Journal of Internal Mvdiciiw. 226(5). ?:\9-?>24.

Bowling. A. (1997). Research meiiwds in

heairih Philadelphia: Open University Press.

Christenscn. A.J.. BenoLsch. E.G.. & Smith.

T.W. (1997). Delcnninants of regimen adherence in renal dialysis. In D.S.

Gochman (Ed.). Handhook of iwallli

hi-ijavior re.scarih: pari 2: Provider

delerniinants. (pp. 231-244). New York: Plenum Pres.s.

Cybulsky. A.V.Malni. A.. &Hotlomby.DJ.

(1985). Effeels of high sodium dialysate during maintenance hemodialysis. Ncphron. 4U I), 57-61.

This is a NIVEL certified Post Print, more info at http://www.nivel.eu

Mistiaen, P. Thirst, interdialytic weight gain, and thirst interventions in hemodialysis patients: a literature

review. Nephrology Nursing Journal: 2001, 28(6), 601-604, 610-615

Daugirdas. J.T..AI Kudsi. R.R.. Ing. T.S.,& Norusis. M.J. (1985). A double-blind evaluation of sodium

gradient hemodialysis. Americun Jotirnai of

Nei>lm)lofi\:50). 163-168.

De Nour. A.K..&Czac/kes. J.W. |19X{)). A saliva substitule as a UK>I in decreasing overdrinking in dialysis patients.

Israelian Journai of Medical .Sciences.

/6(|). 43-44.

Dominic. S.C. Ramaehandran. S., Somiah, S.. Mani. K., & Dominie. S.S. (1996).

Quenching ihe thirst in dialysis patients. Ncpluvti. 7.?(4). 597-600.

Ebel, H.. Laage. C, Ketichel. M.. Ditimar.

A., Saurc. B.. Ehlcn/. K., & Lange. H.

(1997). Impael ol profile haemodialysis on intra-/extracelhilar Huid shifis and the release of vasoaetive hormones

in elderly patients on regular dialysis ireatment. Nephron. 750). 264-271.

Fitzsimons. J.T. (1998). Angiotensin, thirst, and sodium appetite. Phxsiolngy

Review. 78(3). 5S3-6K6.

Giovannetti. S.. Barsotti, G., Cupisii, A., Moretli. E.. Agostini. B., Posclla. L., Gazzetti. P.. Dani. L., Aloi.si. M..

& Antonelll. A. (1994). Dipsogenic factors operating in chronic uremies on maintenanee hemodialysis. Nephron.

66(4).413-420.

Goverde. K.. & Grypdonck. M. (i99S).

[Living with dialysis: A study of the experience of patients treated in a passive dialysis eenter|. Verpieefikiinde.

/.?(3). 217-225.

Graziani. G.. Badalamenti, S.. De! Bo. A..

Marabini. M.. Gazzano. G.. Como, G., Vigano. E., Ambroso. G.. & Morganti.

A. (1993). Abnormal hemodynamies and elevated angiotensin II plasma levels in polydipsic patients on

regular hemodialysis treatment. Kidney

International. 44( I). 107-114.

Hays. R.D.. Kallieh. J.D.. Mapes. D.L..

Coons. S.J.. & Carter. W.B. (1994).

Development of the kidney disease quality of life (KDQOL) instrument.

Qiudi'ry of Life Research. .^(5). 329-338.

Heidbreder. E.. Bahner. U.. Hess, M., Geiger. H.. Gotz. R.. Kirsten. R..

Raseher. W., & Heidtand, A. (1990).

[Regulation of thirst in end-stage kidney insufficiency [. Klini.sche

Wodicnschrift. 6,*^(22). 1127-1133.

Klang. B.. & Clyne. N. (1997). Well-being and funetional ability in uraemic patients before and after having

started dialysis treatment. Scandinavian

Joitrmti of Caring Sciences, HO). 159- 166.

K(K)istra. M.P.. Vos. J.. Koomans. H.A.. & Vos. P.F. (1998). Daily home haemodiaiysis in The Netherlands: Effects on

metabolic eontrol. haemodynamies.

and quality of life. Nepiiroiof^y.

Dialysis and Transpiantation. /,^(l i).

2853-2860.

Kuriyama. S.. Tomonari, H., &. Sakai. O.

(1996). Effeet of eilazapril on hyperdipsia in hemodialyzed patients. Blood

Ptirijkation. /-/(I). 35-41.

Leggat. J.E.. Orzol. S.M.. Huibert-Shearon.

T.E.. Golper, T.A.. Jones. C.A.. Held.

P.J.. & Port, F.K. (1998).

Noncomplianee in hemodialysis: Predictors and survival analysis.

American Journal of Kidney Diseases.

n(\). 139-145.

Levin. A.. & Goldstein. M.B. (1996). The benefits and side effects of ramped hypertonie sodium dialysis. Journal of

the Amencan Society of Nephroiogy.

7(2), 242-246.

Lin. C.C.. & Liang. C.C. (1997). The relationship between health loeus of eontrol and compliance of

hemodialysis patients. Kaohsiung Journal of Medicai

Science, !i(A),2A?,-15A.

Martinez-Vea, A., Gareia. C. Gaya. J..

Rivera. E. & Oliver. J.A. (1992).

Abnormalities of thirst regulation in patients with chronic renal failure on hemodiatysis. American Journal of

Ncpiiioiogy, /2( 1-2). 73-79.

Oldenburg. B.. MacDonald. G.J.. & Perkins.

RJ. (1988). Factors influencing excessive thirst and fluid intake in dialysis patients. Dialysis (& Transpiantation.

Oldenburg. B.. MacDonald. G.J.. & Shelley.

S. (1988). Controlled trial of enaiaprii in patients with chronic fluid overload undergoing dialysis. British Medical

Journal (Ctin Res Ed). 296(6629), 1089-1091.

Parsons. D.S.. Yuill. E.. Llapitan. M.. & Hairis.

D.C. (1997). S<xlium nnxieting and profiled ullrafiltration in conventional haemixlialysis. Ncpiiroiogw 3, 177-181.

This is a NIVEL certified Post Print, more info at http://www.nivel.eu

Mistiaen, P. Thirst, interdialytic weight gain, and thirst interventions in hemodialysis patients: a literature

review. Nephrology Nursing Journal: 2001, 28(6), 601-604, 610-615

Rosansky. S.J.. Johnson. K.L.. & McConnelL J. (1993). Use of transdermal ctonidine in ehronie hemodialysis patients.

Clinicai Nephroto^y. J9{\).

32-36.

Sadowski. R.H., Allred, E.N.. & Jabs. K.

(1993). Soditim modeling ameliorates intradiaiytic and interdialytic symptoms in young hemodialysis patients.

Journal of tiie American Society of

Neplmtiogy, 4(5). 1192-1198.

Sang. G.L.. Kovithavongs. C, Ulan. R.. & Kjellstrand, CM. (1997). Sodium ramping in hemodialysis: a study of beneficial

and adverse elTects.

American Journal of Kidney Di.scases.

Virga, G., Mastrosimone, S.. Amici. G., Munaretto. G.. Gastaldon, K. & Bonadonna, A. (1998). Symptoms

in hemodialysis patients and their relationship with bioehemieal and demographie parameters. International Journai of

Artificial Organs. 2I{ 12). 788-793.

Welch, J.L.. & Davis, J. (2(KX)). Self-care strategies to reduce fluid intake and eontrol thirst in hemodialysis patients.

Nephrology Nursing Journal, 27(4).

393-395.

Winh. J.B., & Folstein. M.F. (19X2). Thirst and weight gain during maintenance hemodialysis. Psyciwsontatics, 23i\\).

1125-1134.

Yamamoto. T.. Shimizu, M.. Morioka, M..

Kitano, M., Wakabayashi. H.. & Aizawa,N. (1986). Role of angiotensin II in the pathogenesis of hyperdipsia in ehronie

renal failure. JAMA. 256(5).

This is a NIVEL certified Post Print, more info at http://www.nivel.eu

Mistiaen, P. Thirst, interdialytic weight gain, and thirst interventions in hemodialysis patients: a literature

review. Nephrology Nursing Journal: 2001, 28(6), 601-604, 610-615

This is a NIVEL certified Post Print, more info at http://www.nivel.eu

Mistiaen, P. Thirst, interdialytic weight gain, and thirst interventions in hemodialysis patients: a literature

review. Nephrology Nursing Journal: 2001, 28(6), 601-604, 610-615

TABLES

This is a NIVEL certified Post Print, more info at http://www.nivel.eu

Mistiaen, P. Thirst, interdialytic weight gain, and thirst interventions in hemodialysis patients: a literature

review. Nephrology Nursing Journal: 2001, 28(6), 601-604, 610-615

This is a NIVEL certified Post Print, more info at http://www.nivel.eu

Mistiaen, P. Thirst, interdialytic weight gain, and thirst interventions in hemodialysis patients: a literature

review. Nephrology Nursing Journal: 2001, 28(6), 601-604, 610-615

This is a NIVEL certified Post Print, more info at http://www.nivel.eu

Mistiaen, P. Thirst, interdialytic weight gain, and thirst interventions in hemodialysis patients: a literature

review. Nephrology Nursing Journal: 2001, 28(6), 601-604, 610-615

This is a NIVEL certified Post Print, more info at http://www.nivel.eu

Mistiaen, P. Thirst, interdialytic weight gain, and thirst interventions in hemodialysis patients: a literature

review. Nephrology Nursing Journal: 2001, 28(6), 601-604, 610-615

FIGURES

This is a NIVEL certified Post Print, more info at http://www.nivel.eu