here. 1 - News & Events - Wake Forest University

Admiralty-LOS.11 May 16, 2014 FINAL DRAFT

THE INTERFACE OF ADMIRALTY LAW AND OCEANS LAW

George K. Walker*

Lawyers practicing admiralty and maritime law must be aware of oceans law, i.e.

, the international law of the sea, and general international law, as they apply to their clients.

1

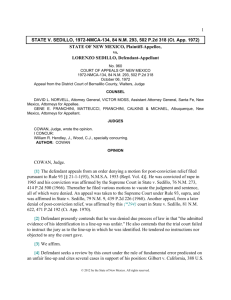

A recent United States District Court opinion in Tarros S.p.a. v. United States

2 is but one example

1

U.S. admiralty lawyers were once known as proctors in admiralty, as distinguished from attorneys at law or counselors in equity. My 1967 admission to the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia recites this. Today the distinction is gone, except in organizations like the Maritime Law Association of the United States (MLA), the U.S. national affiliate of the

Comite Maritime Internationale (CMI), sponsor of treaties governing admiralty practice. See also infra note 171 and accompanying text. I am an MLA Proctor member. Today lawyers may advertise their services; previously two specialties – patents and trademarks, and admiralty lawyers – could do so. Compare ABA, Canons of Professional Ethics, canon 27 (1909, amended

1951) with id.

, Model Rules of Professional Conduct, R. 7.2, 7.4(c) (2013). U.S. admiralty practice has always had an international perspective, sometimes with a civil law ancestry.

English admiralty lawyers were known as civilians; some early English admiralty law had civil law roots; the High Court of Justice originally had a Probate, Admiralty and Divorce Division, for the “wrecks of ships, wills and marriages,” because all three bodies of law had Roman (civil) law roots. U.S. admiralty jurisdiction is more extensive than what English courts had, due to

U.S. Const., art. III § 2's extending U.S. courts’ competence “to all Cases of admiralty and maritime jurisdiction.” See also Judiciary Act of 1789 § 9, reenacted as 28 U.S.C. § 1333(1)

(2012); New England Mut. Marine Ins. Co. v. Dunham, 78 U.S. (11 Wall.) 1, 21 (1870), approving Justice Joseph Story’s “learned and exhaustive” opinion in De Lovio v. Boit, 7 F.Cas.

418 (C.C.D. Mass. 1815) (No. 3776). Admiralty law can be a mix of comparative law as well as public international law, cf., e.g.

, The China, 74 U.S. 53 (1869) (analysis of English, U.S.

pilotage law, general civil law principles). For a U.S. practitioner, there are other analyses, the place of the law of the 50 states of the Union in U.S. admiralty law, cf.

, e.g.

, Yamaha Motor

Corp. v. Calhoun, 516 U.S. 199, 206-14 (1996) and a later decision, Calhoun v. Yamaha Motor

Corp., 216 F.3d 338, 342-51 (3d Cir. 2000) (“maritime but local” doctrine); and state court litigation under 28 U.S.C. § 1333(1)’s saving to suitors clause but applying federal admiralty law, cf., e.g., Kermarec v. Compagnie Generale Transatlantique, 358 U.S. 625, 628 (1959)

(collecting cases). None of these features of admiralty law – scope of admiralty jurisdiction, or a possibility of applying local, i.e.

state law – are directly at stake in this analysis, but U.S.

admiralty attorneys are aware of these problems.

2

Tarros S.p.a. v. United States, 2014 A.M.C. 50 (S.D.N.Y. 2013).

1

of interface issues admiralty lawyers, whether in the private or public sectors, may confront.

This article tries to analyze some of these intricate relationships.

Part I dives into the relationship of national admiralty law and oceans law in Part I; Part

II offers a broader view of general international law issues as they may apply to admiralty cases.

Although the focus is mostly on admiralty and maritime law of the United States as it relates to international law, these observations may be relevant for admiralty practitioners in other countries.

I. National Admiralty Law and General Oceans Law

The 1958 and 1982 law of the sea conventions have two subtle but important exceptions to their application. The first is the “other rules” clauses in these agreements, which declare that they are subject to other rules of international law, 3 the traditional view being that the clauses

3 The phrase varies slightly in the treaties. U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea

(hereinafter UNCLOS), pmbl., arts. 2(3) (territorial sea); 19, 21, 31 (territorial sea innocent passage); 34(2) (straits transit passage); 52(1) (archipelagic sea lanes passage; incorporation by reference of Articles 19, 21, 31); 58(1), 58(3) (EEZ); 78 (continental shelf; coastal State rights do not affect superjacent waters, i.e., territorial or high seas; coastal State cannot infringe or unjustifiably interfere with "navigation and other rights and freedoms of other States as provided in this Convention"); 87(1) (high seas); 138 (the Area); 293 (court or tribunal having jurisdiction for settling disputes must apply UNCLOS and "other rules of international law" not incompatible with UNCLOS); 303(4) (archeological, historical objects found at sea, "other international agreements and rules of international law regarding the protection of objects of an archeological and historical nature"); Annex III, art. 21(1), Dec. 10, 1982, 1833 U.N.T.S. 3, 397; Convention on the High Seas, art. 2, Apr. 29, 1958, 13 U.S.T. 2312, 450 U.N.T.S. 82 (hereinafter High Seas

Convention); Convention on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone, arts. 1(2), 22(2), Apr. 29,

1958, 15 U.S.T. 1606, 516 U.N.T.S. 205 (hereinafter Territorial Sea Convention). Convention on the Continental Shelf, Apr. 29, 1958, 15 U.S.T. 478, 499 U.N.T.S. 311 (hereinafter

Continental Shelf Convention) and Convention on Fishing and Conservation of the Living

Resources of the High Seas, Apr. 29, 1958, 17 U.S.T. 138, 559 U.N.T.S. 285 (hereinafter Fishing

Convention) do not have other rules clauses, but they declare that waters within their competence are high seas areas. Continental Shelf Convention, supra art. 3; Fishing

Convention, supra arts. 1-2. The same is true for the contiguous zone next to the territorial sea; beyond the territorial sea, the contiguous zone is a high seas area. UNCLOS, supra art. 33(1);

2

mean the law of armed conflict.

4

In situations where treaties other than the law of the sea conventions would apply, the law of treaties would say that the treaty norms may be suspended or, under the older view, terminated because of armed conflict.

5

In the United States the

Territorial Sea Convention, supra art. 24(1). See also High Seas Convention, supra art. 1, defining “high seas” as all parts of the sea not included in a State’s territorial sea or internal waters. Agreement Relating to the Implementation of Part II of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982, July 28, 1994, 1836 U.N.T.S. 3, 42 amends

UNCLOS, supra but is not relevant to the ensuing analysis.

4

There is a view that the clauses may have a more expansive meaning in certain

UNCLOS, supra note 3, contexts. George K. Walker, gen. ed., Definitions for the Law of the

Sea: Terms Not Defined by the 1982 Convention 267-72 (2012).

5 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, May 23, 1969, 1155 U.N.T.S. 331

(hereinafter Vienna Convention) does not recite rules when treaties apply during armed conflict.

See id. art. 73. International law is in disarray on whether war terminates or suspends treaties.

Modern sources, citing pacta sunt servanda ( cf. id. art. 26), emphasize suspension for the duration of a conflict. Id . art. 60(5) declares that breach of a treaty governing humanitarian law protecting the human person is not subject to the usual treaty breach rules. The Convention does not address the core issue of general treaty application, nonapplication, or suspension. Parties might invoke impossibility of performance or fundamental change of circumstances, cf. Vienna

Convention, supra , arts. 61-62. See generally Gabcikovo-Nagymoros Project (Hungary v.

Slovakia), 1997 I.C.J. 7, 64 (hereinafter Project Case) (confirming Fisheries Jurisdiction [U.K. v.

Ice.], 1973 I.C.J. 3, 63 ruling that Vienna Convention art. 62, supra codifies custom);

International Law Commission, Report on the Work of Its Eighteenth Session, U.N. Doc.

A/6309/Rev.1 (1966), reprinted in 2 (1966) Y.B. Int’l L. Comm’n, U.N. Doc.

A/CN.4/Ser.A/1966/Add. 1, at 160, 236, 256-58, 267 (1966); Anthony Aust, Modern Treaty Law and Practice 10-11, 158-60, 257-68, 271-72 (3d ed. 2013); 2 Oliver Corten & Pierre Klein eds.,

The Vienna Conventions on the Law of Treaties: A Commentary 1654-59); James Crawford, Ian

Brownlie’s Principles of Public International Law 377, 390-94 (8th ed. 2012) (reporting 2011 adoption of International Law Comm’n, Draft Articles, Report on the Work of Its 66th Session,

U.N. Doc. A/66/10, at 173-217 [Supp. No. 10, 2011]); Louise Doswald-Beck, Human Rights in

Times of Conflict and Terrorism 192-93 (2011) (noting problem of non-international armed conflicts); 5 Hackworth, Digest § 513, at 390; compare Institut de Droit International, The

Effects of Armed Conflicts on Treaties , Aug. 28, 1985, 61(2) Annuaire 278 (1980) with id.

,

Regulations Regarding the Effect of War on Treaties , 1912, 7 Am. J. Int’l L.153 (1913);

Research in International Law of the Harvard Law School, Law of Treaties: Draft Convention with Comment , art. 35, 29 id. 663, 664 (1935 Supp.); Robert Jennings & Arthur Watts,

Oppenheim’s International Law §§ 584, 649-51, 655 (9th ed. 1992); Lord McNair, The Law of

Treaties chs. 30, 35-36, 42, 43 (1961); 2 Lassa Oppenheim, International Law § 69 (Hersch

Lauterpacht ed. 1955); Restatement (Third) of the Foreign Relations Law of the United States §§

3

Executive decides if an international agreement is no longer in effect under the law of treaties.

6

And even if no treaty applies in a given situation, i.e.

, that the customary law of the sea would apply, the law of armed conflict as a lex specialis would be an exception to the general law.

7

321, 335-36 (1987) (hereinafter Restatement); Ian Sinclair, The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties 6, 163, 165, 188-96 (2d ed. 1984); Herbert W. Briggs, Unilateral Denunciation of

Treaties: The Vienna Convention and the International Court of Justice, 66 Am. J. Int’l L. 51

(1974); Doswald-Beck & Sylvain Vite, International Law and Human Rights Law , 1993 Int’l

Rev. Red Cross 94; G.G. Fitzmaurice, The Judicial Clauses of the Peace Treaties , 73 R.C.A.D.I.

255, 312 (1948); Cecil J.B. Hurst, The Effect of War on Treaties , 2 Brit. Y.B. Int’l L. 37 (1921);

Richard D. Kearney & Robert E. Dalton, The Treaty on Treaties , 64 Am. J. Int’l L. 495, 557

(1970); David Weissbrodt & Peggy L. Hicks, Implementation of Human Rights and

Humanitarian Law in Situations of Armed Conflict , 1993 Int’l Rev. Red Cross 120. Some treaties say whether they are in force during war, e.g.

, Convention on International Civil

Aviation, art. 89, Dec. 7, 1944, 61 Stat.1180, 15 U.N.T.S. 295 (in force during armed conflict)

(hereinafter ICAO Convention). The U.S. Department of State and U.S. courts have declared that parts of the Vienna Convention, supra , not in force for the United States, restate customary international law or are an authoritative guide. See, e.g., Introductory Note , 1 Restatement, supra at 144-45.

6 Charlton v. Kelly, 229 U.S. 447, 469-75 (1913) (political branches must decide if there has been a treaty breach, the international obligation remains until they do; absent a decision, courts must enforce treaty); Trans World Airlines, Inc. v. Franklin Mint Corp., 466 U.S. 243, 252

(1984) (parties cannot invoke rebus sic stantibus, i.e.

, fundamental change of circumstances, for

States parties to a treaty); Goldwater v. Carter, 817 F.2d 697, 706 (D.C. Cir.) (executive must decide if United States considers fundamental change of circumstances has occurred; courts cannot under Separation of Powers doctrine) (per curiam), vacated , 444 U.S. 996 (1979).

7 High Seas Convention, supra note 3, pmbl. declares its terms are “generally declaratory of established principles of international law.” Since id. art. 2 recites that high seas freedoms are subject to other rules of international law, it follows that at least the high seas were subject to the law of armed conflict as part of the international customary lex specialis in 1958. R.R. Churchill

& A.V. Lowe, The Law of the Sea 15 (3d ed. 1999); 1 D.P. O’Connell, International Law of the

Sea 385, 474-76 (1982). Before States began ratifying UNCLOS, supra note 3, and before and after the breakup of the USSR and Yugoslavia and the unification of Germany, 66 countries became High Seas Convention, supra parties. United States Department of State, Treaties in

Force: A List of Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States in Force on

January 1, 2012, at 423 (2013) (hereinafter TIF). Treaty succession principles suggest that more than 66 States may be Convention parties, unless they ratified UNCLOS; its art. 311(1) declares

UNCLOS supersedes the High Seas Convention, supra as between parties to both. See also

Vienna Convention on Succession of States in Respect of Treaties, Aug. 23, 1978, 1946

U.N.T.S. 3 (hereinafter Succession Convention); Project Case, supra note 5, 1997 I.C.J. at 71

4

The demise of Mommar Ghaddaffi’s regime in Libya in 2011 is one example of how admiralty rules may be intertwined with general oceans law.

In the Libya crisis, certain countries, e.g.

, the United States, froze Libyan assets.

8

Some of these may or could have involved shipping or payment for ocean carriage. If so, this directly affected oceans trade; the freeze orders were valid as proportional economic reprisals 9 to compel

(Succession Convention, supra , art. 12 reflects custom); Aust, supra note 5, ch. 21; Corten &

Klein, supra note 5, at 1646-49 (Vienna Convention, supra note 5, art. 73, declares id . does not recite treaty succession rules); Crawford, supra note 5, at 438-43; Jennings & Watts, supra note

5, § 62, at 211-13; Restatement, supra note 5, § 210 (generally reflects Succession Convention, supra rules); Sinclair, supra note 5, at 6; Symposium, State Succession in the Former Soviet

Union and in Eastern Europe , 33 Va. J. Int’l L. 253 (1993); George K. Walker, Integration and

Disintegration in Europe: Reordering the Treaty Map of the Continent , 6 Transnat’l Law 1

(1993). Few States have ratified the Succession Convention, supra . United Nations Office of

Legal Affairs, Status of Treaties, Multilateral Treaties Deposited with the Secretary General ch.

23, at 2 (May 18, 2014), http://treaties.un.org/Pages/DB.aspx?path=DB/MTDSG/page1_en.xml

(hereinafter Multilateral Treaties).

8 Exec. Order No. 13566 (Feb. 25, 2011), 76 Fed. Reg. 11315 (Mar. 2, 2011) (freeze, block on assets in United States, prohibiting certain transactions with Libya).

9 Most commentators say use of force as a reprisal during situations not involving armed conflict violates international law. Project Case, supra note 5, 1997 I.C.J. at 54; Military &

Paramilitary Activities in & Against Nicaragua (Nicar. v. U.S.), 1986 I.C.J. 14, 127 (hereinafter

Nicaragua Case); Declaration on Principles of International Law Concerning Friendly Relations

& Co-Operation Among States in Accordance with the Charter of the United Nations, Principle

6, G.A. Res. 2625, U.N. GAOR, 25th Sess., Supp. No. 28, U.N. Doc. A/8028 (1970);

International Law Commission, Draft Articles on State Responsibility for Internationally

Wrongful Acts, arts. 22, 49-54 in Report of the International Law Commission, 53d Sess., U.N.

Doc. A/56/10 (2001) (hereinafter ILC Draft Articles), commended to States by U.N. General

Assembly Resolution 56/83, ¶ 3 (Dec. 12, 2001); Roberto Ago, Addendum to Eighth Report on

State Responsibility , U.N. Doc. A/CN.4/318 & Add. 1-4, Y.B. Int’l L. Comm. 13, 69-70 (1981);

D.W. Bowett, Self-Defence in International Law 13 (1958); J.B. Briefly, The Law of Nations

401-02 (Humphrey Waldock ed., 6th ed. 1963); Ian Brownlie, International Law and the Use of

Force by States 281 (1963), 2 Oppenheim, supra note 5, §§ 43, 52a; Julius Stone, Legal Controls of International Conflict 286-97 (1959 rev.); A.R. Thomas & James C. Duncan eds., Annotated

Supplement to the Commander's Handbook on the Law of Naval Operations, ¶¶ 6.2.3, 6.2.3.1

(Nav. War C. Int'l L. Stud., v. 73, 1999) (hereinafter Thomas & Duncan); D.W. Bowett,

Reprisals Involving Recourse to Armed Force , 66 Am. J. Int’l L. 20 (1972); David Caron, The

ILC Articles on State Responsibility: The Paradoxical Relationship Between Form and

5

Libya to comply with international law. They were unquestionably valid under the U.S.

National Emergencies Act and the International Emergency Economic Powers Act

10

and therefore binding as national law on U.S. shipping and related interests, e.g.

, transmission of international letters of credit, bills of lading, etc., related to shipping.

At about the same time the European Union issued similar restrictions.

11 These controls did not directly affect U.S.-based interests, but they shut down EU members’ economic relations with Libya in the same way. U.S. and other States’ maritime interests were affected, to the extent that their trade networks with EU members meshed with the EU restrictions.

The U.S. and EU restrictions can also be seen as valid reprisals, not involving the use of force.

12 In both cases these restrictions could also be seen as exceptions under “other rules of law” principles applying to the usual free transport of goods on the seas.

13

In either case admiralty lawyers had to be aware of, and to advise their clients of, these restrictions. For U.S. interests, the President’s executive order was mandatory if it applied to those them, even if there was no direct applicability to a lawyer’s clients, he or she had to take

Authority, 96 Am. J. Int’l L. 857, 858 (2002) (criticism of ILC Draft Articles, supra ); Rosalyn

Higgins, The Attitude of Western States Toward Legal Aspects of the Use of Force , in Anthony

Cassesse, The Current Legal Regulation of the Use of Force 435, 444 (1986); cf. UK Ministry of

Defence, The Manual of Armed Conflict ¶¶ 16.16-16,17 (2004) (hereinafter UK Manual); but see Yoram Dinstein, War, Aggression and Self-Defence 244-55 (5th ed. 2011) (States can use reprisals involving force during peacetime).

10 50 U.S.C. §§ 1601-51 (2012); 50 U.S.C. §§ 1701-07 (2012), cited inter alia in

President Obama’s Libya freeze order, supra note 8.

11

European Union Council Regulation 204/11, 2011 O.J. (L 58) 1 (Mar. 2, 2011)

(hereinafter EU Council Regulation 204/11).

12

See supra notes 7-11 and accompanying text.

13

See supra note 3 and accompanying text.

6

them into account in advising clients on the developing situation in Libya as well as considering whether the lawyer’s clients had dealings with clients affected by the restrictions.

Another exception to applying general oceans law was U.N. action, and the U.N. Security

Council in particular. After countries like the United States and collective organizations like the

EU acted, the Council voted resolutions to the same effect and added authority for States to interdict Libya-bound shipping.

14 The interdictions, and diverting shipping from Libyan ports,

14

Peace and Security in Africa, S.C. Res. 1970, ¶¶ 9-24, U.N. Doc. S/RES/1970 (2011)

(imposing inter alia arms embargo, travel bans, assets freeze). Resolution 1970, which appeared to forbid arms shipments to the rebels as well as the Gadahafi-led government, had different interpretations. France, which had recognized the rebel government, said it airdropped arms and ammunition to allow safe delivery of essential medical and other relief supplies to the rebels.

David Jolly & Kareem Fahim, France Says It Gave Arms to the Rebels in Libya , N.Y. Times,

June 30, 2011, at A4. Russia protested, saying this violated the embargo. Reuters, Russia Says

France Is Violating Embargo , id., July 1, 2011, at A7. A later Council resolution approved a nofly zone over Libya and authorized “all necessary action” to protect civilians. S.C. Res. 1973,

U.N. Doc. S/RES/1973 (2011). The United States initially led no-fly operations, including destruction of Libya’s air defense systems to insure dominance of the skies over Libya. Tarros

S.p.a. v. United States, 2014 A.M.C. at 51-53; James Foggo, A Promise Kept , U.S. Nav. Inst.

Proc. 24 (June 2012); Jordan J. Paust, Constitutionality of U.S. Participation in the United

Nations-Authorized War in Libya , 26 Emory Int’l L. Rev. 43-45 (2012). The operations then went under North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) command, with some non-NATO countries ( e.g.

, Qatar) contributing, soon thereafter. Some NATO countries declared they would not participate. Italy, a NATO member dependent on Libyan oil, “reluctantly” decided to allow use of its bases and “de facto suspended” a 2008 friendship treaty with Libya. The Arab League supported the resolution. Elisabeth Bumiller & David D. Kirkpatrick, Obama Threatens

Military Action Against Qaddafi , N.Y. Times, Mar. 19, 2011, at A1; Helene Cooper & Steven

Lee Myers, Shift by Clinton Helped Persuade President to Take a Harder Line , id . at A1; Adam

Entous et al., Europe Pressure , Arab Support Helped Turn U.S., Wall St. J., supra at A5; Steven

Erlanger, France and Britain Lead Military Push on Libya , N.Y. Times, supra at A9; Keith

Johnson et al., World Rallies to Curb Gadhafi, Wall St. J., Mar. 19-20, at A1. There were debates about U.S. participation, i.e.

, because of the War Powers Resolution, 50 U.S.C. §§ 1541-

48 (2012), and its time clocks. Charlie Savage & Mark Landler, White House Defends

Continuing U.S. Role in Libya Operation , N.Y. Times, June 18, 2011, at A13 (Congressional criticism); Charlie Savage, 2 Top Lawyers Lose Argument on War Power , id., June 18, 2011, at

A1 (division among Obama administration lawyers). A U.S. House of Representatives resolution overwhelmingly rejected a bill authorizing U.S. military operations in Libya but defeated a bill limiting spending on Libyan operations, following a Senate bill. Jennifer

7

was taken under law of armed conflict rules.

15

This action fell within law of armed conflict principles, i.e.

, within the “other rules” principles excluding application of the law of the sea.

One example was interception of S.S. Vento, a Cyprus-flagged general cargo ship Tarros

S.p.a. headquartered in La Spezia, Italy, chartered for a voyage to Tripoli, Libya with a general cargo of 168 containers. U.S. Stout, a U.S. Navy destroyer and part of the maritime interdiction force operating against the Ghadaffi regime under U.N. Security Council Resolutions and U.S.

Steinhauer, House Refuses Backing on Libya; Won’t Cut Funds, id.

, June 23, 2011, at A1. The

President, faced with the WPR 60-day reporting deadline, wrote Congressional leaders on May

20, 2011 that active military operations had been turned over to NATO leadership and that the

U.S. role had been limited to “non-kinetic support,” offshore weapons that destroyed Libyan air defense systems, search and rescue, and “precision strikes by unmanned aerial vehicles” against

Libyan targets. Paust, supra at 45. The Security Council resolutions had followed practice during the disintegration of Yugoslavia. S.C. Res. 781, U.N. Doc. S/RES/781 (1992) (ban on military flights over Bosnia-Herzegovina); S.C. Res. 787, U.N. Doc. S/RES/787 (1992)

(shipping controls in the Adriatic Sea off former Yugoslavia, on the Danube River). As the

Libyan crisis ebbed but did not end after Ghadaffi’s death, Council resolutions have paralleled

Libya’s slow, halting progress toward stable governance. As has been the case in similar cases, these resolutions often incorporate earlier resolutions by reference, and a complete picture of a situation requires reading all of them. See, e.g., S.C. Res. 2009, U.N. Doc. S/RES/2009 (2011), establishing the U.N. Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL), modifying the arms embargo and assets freeze, and ending, for the time being, the no-fly zone; S.C. Res. 2016, U.N. Doc.

S/RES/2016 (2011), ending other provisions of Resolution 1973, regarding protection for civilians through regional organizations and ending the no-fly zone; S.C. Res. 2040, U.N. Doc.

S/RES/2040 (2012) and S.C. Res. 2095, U.N. Doc. S/RES/2095 (2013), extending UNSMIL’s authority into early 2014. The EU Council has adopted many regulations modifying EU Council

Regulation 204/11, supra note 11, paralleling the Security Council action. See generally EU

Doc. 2011R0204 - EN - 20.05.2013 0 013.001, at 1 (2014). Presidential Notice of Feb. 23, 2012,

Continuation of the National Emergency with Respect to Libya, 77 Fed. Reg. 11381 (Feb. 24,

2012) continued the national emergency declared under 50 U.S.C. §§ 1701–06, supra note 10, for another year. These later developments point to the need for admiralty counsel to continue to monitor fluid situations to assist clients as a crisis builds and dissipates.

15 See, e.g.

, International Lawyers & Naval Experts Convened by the International

Institute of Humanitarian Law, San Remo Manual on International Law Applicable to Armed

Conflicts at Sea ¶¶ 121, 135 & cmts. (Louise Doswald-Beck ed. 1995) (hereinafter San Remo

Manual); Thomas & Duncan, supra note 9, ¶ 7.6.1 at 389; UK Manual, supra note 9, ¶¶ 13.92,

13.94, 13.111.

8

law, intercepted Vento and directed her master to proceed to Trapani, Italy, for inspection of her cargo. Eventually Vento proceeded to Malta, escorted by Stout. Vento’s owners then directed the ship to return to La Spezia.

16

Her owner filed a claim with the U.S. Navy, which was denied, and then filed suit against the United States under the Public Vessels Act in the United States

District Court for the Southern District of New York. The Court denied relief under the political question doctrine and the related principle of military discretion related to military operations, also rejecting plaintiff’s claims for binding application of international law through Security

Council Resolutions 1970 and 1973, binding rules under North Atlantic Treaty orders for enforcing the embargo, and rules under the 1982 U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea.

17

The Libya crisis illustrates two other, in this case concentric, applications of exceptions to general oceans law. First, the Treaty of Lisbon mandates compliance with resolutions coming under EU governance.

18 Second, the U.N. Charter provides for mandatory application of

Security Council “decisions.” 19 U.N. Members must comply with this kind of resolution. Other

16 Tarros S.p.a. v. United States, 2014 A.M.C. at 53-55.

17 Id. 56-78, inter alia citing Public Vessels Act, 46 U.S.C.A. §§ 31101-13 (2012); see also supra note 14 and accompanying text; infra note 26 and accompanying text; North Atlantic

Treaty, Apr. 4, 1949, 63 Stat. 2241, 34 U.N.T.S. 243, which has expanded its territorial scope through accessions of 16 other States since 1949. See generally TIF, supra note 7, at 438-40.

18 Treaty of Lisbon Amending the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty Establishing the European Community, Dec. 13, 2007, art. 288, 2007 O.J. (C 306) 51.

19 U.N. Charter arts. 25, 48, 94(2), 103; see also 1 & 2 The Charter of the United

Nations: A Commentary 786-854, 1376-84, 1957-71, 2110-37 (Bruno Simma, Daniel-Erasmus

Khan, Georg Nolte, Andreas Paulus eds., Nikolai Wessendorf ass’t ed.., 3d ed. 2012)

(hereinafter Charter Commentary); San Remo Manual, supra note 15, ¶¶ 7-9; Robin R.

Churchill, Conflicts between United Nations Security Council Resolutions and the 1982 United

Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea , in International Law and Military Operations 148-49

(Nav. War C. Int’l L. Stud. v. 84, Michael L. Karsten ed. 2008); W. Michael Reisman, The

Constitutional Crisis in the United Nations , 87 Am. J. Int’l L. 83, 87 (1993) (principles flowing

9

U.N. resolutions, i.e.

, Council resolutions recommending action or calling for action, as well as most U.N. General Assembly resolutions, are not per se mandatory,

20

but they may become binding international law through States’ acceptance of them as customary norms.

21

Thus even in these cases an admiralty lawyer must be aware of the potential impact of them on clients.

There are two more considerations to application of U.N. law. First, some countries, notably the United States, would seem to consider law derived from the Charter as non-selfexecuting, i.e.

, a U.S. authority, often considered to be Congress, for implementing treaties like the Charter 22 but possibly also the President through Article II powers under the Constitution and from Council decisions pursuant to arts. 25, 48, 103 are treaty law binding U.N. Members and override other treaty obligations).

20 U.N. Charter arts. 10-11, 13-14, 33, 36-37, 39-41; see also Sydney D. Bailey & Sam

Daws, The Procedure of the UN Security Council 18-21, 236-37 (3d ed. 1998); Crawford, supra note 5, at 14; Jorge Castenada, Legal Effects of United Nations Resolutions 78-79 (Alba Amoia trans. 1969); Jennings & Watts, supra note 5, § 16; Restatement, supra note 5, § 103(2)(d) & r.n.2; Charter Commentary, supra note 19, at 461-506, 525-66, 1069-85, 1119-60, 1272-1329;

Churchill, supra note 19, at 146-48 (analysis in UNCLOS, supra note 3 context, noting division of authorities).

21 Crawford, supra note 5, at 192-93; Jennings & Watts, supra note 5, § 16; Restatement, supra note 5, § 103; W. Michael Reisman, Acting Before Victims Become Victims: Preventing and Arresting Mass Murder , 40 Case W. Res. Int’l L. J. 57, 72-73 (2007-08), citing Uniting For

Peace Resolution, G.A. Res. 377, ¶ 1, U.N. Doc. A.1775 (Nov. 3, 1950), invoked during the

Korean War to continue U.N. operations after USSR vetoes ended Security Council action;

Legal Consequences of Constr. of a Wall in the Occupied Palestine Terr., 2004 I.C.J. 136, 148-

51 (adv. op. July 9); Certain Expenses of the United Nations, 1952 I.C.J. 151, 163-71 (adv. op.

July 20). See also George K. Walker, The Tanker War 1980-1988: Law and Policy 175-77

(Nav. War C. Int’l L. Stud. v. 74, 2000) (hereinafter The Tanker War).

22 Cf. Medellin v. Texas, 552 U.S. 491, 503-23 (2007). Medellin considered the effect on

U.S. law of International Court of Justice judgments and relevant U.N. Charter and I.C.J. Statute provisions. Medellin did not decide whether all or some other Charter provisions are non-selfexecuting, requiring national law implementation, or if the Executive can implement Charter law under its U.S. Constitutional authority. Those issues remain open for other cases, e.g.

, Tarros

S.p.a. v. United States, 2014 A.M.C. at 69-76, to decide.

10

federal legislation for some situations, must act before the Nation is bound as a matter of U.S.

law.

23

Second, how U.N. law, perhaps implemented through national law, applies to rules embedded in traditional admiralty law, is not always clear.

In recent crises the U.N. Security Council has been relatively clear in incorporating these kinds of standards in resolutions governing potential armed conflict at sea.

24

There are other situations where admiralty lawyers must take into account international law as a factor in decisions related to maritime transactions. I list a few.

A. Self-defense in the Charter era

States met the Libyan crisis by individual countries’ economic coercion and collective action through transnational organizations (the EU) and the U.N. Security Council. Notably absent were self-defense claims. In other situations since 1945 countries have asserted the right to individual and collective self-defense. The Charter provides in Article 51:

Nothing in the present Charter shall impair the inherent right of individual or collective self-defense if an armed attack occurs against a Member of the United Nations, until the . . . Council has taken the measures necessary to preserve international peace and security. Measures taken by Members in the exercise of this right of self-defense shall be immediately reported to the . . . Council and shall not in any way affect the authority of the . . . Council under the . . . Charter to take at any time such action as it

58-69.

23 This was another ground for dismissal in Tarros S.p.a. v. United States, 2014 A.M.C. at

24

As the Cold War ended, the first example was the 1990-91 crisis and war over Iraq’s seizure of Kuwait. See generally George K. Walker, The Crisis Over Kuwait, August 1990 -

February 1991 , 1991 Duke J. Comp. & Int’l L. 25.

11

deems necessary . . . to maintain or restore international peace and security.

Like Council decisions, the right to self-defense under the Charter trumps all treaties.

25

There are three issues with respect to self-defense in the Charter era: (1) Is the right limited to

“reactive” self-defense, where a State, States in a collective self-defense organization like

NATO, 26 in a bilateral defense treaty arrangement, or aligned in a coalition, the latter the situations in the 1990-91 Kuwait crisis, 27 or military units or individuals under military command, must await an adversary’s attack before responding while observing principles of necessity and proportionality, i.e.

“reactive” self-defense after “taking the first hit”?

28 Or does

25 U.N. Charter arts. 51, 103; see also supra notes 15, 19 and accompanying text.

26 See North Atlantic Treaty, supra note 17, amended by protocols after 1949; see supra note 17 and accompanying text.

27 See generally Walker, The Crisis, supra note 24.

28 Those arguing that anticipatory self-defense is unlawful in the Charter era include Ian

Brownlie, International Law and the Use of Force by States 257-61, 275-78, 366-67 (1963);

Anthony D'Amato, International Law: Process and Prospect 32 (1987); Dinstein, supra note 9, at 194-200; Louis Henkin, International Law: Politics and Values 121-22 (1995); Philip C.

Jessup, A Modern Law of Nations 166-67 (1948); D.P. O'Connell, The Influence of Law on Sea

Power 83, 171 (1979); 2 Oppenheim, supra note 5, § 52aa, at 156; Ahmed M. Rifaat,

International Aggression 126 (1974); Natalino Ronzitti, Rescuing Nationals Abroad Through

Military Coercion and Intervention on Grounds of Humanity 4 (1985); Tom Farer, Law and War, in 3 Cyril E. Black & Richard A. Falk, The Future of the International Legal Order 30, 36-37

(1971); Yuri M. Kolosov, Limiting the Use of Force: Self-Defense, Terrorism, and Drug

Trafficking, in Lori Fisler Damrosch & David J. Scheffer, Law and Force in the New

International Order 232, 234 (1991) Josef L. Kunz, Individual and Collective Self-Defense in

Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations, 41 Am. J. Int’l L. 872, 878 (1947); Rainer

Lagoni, Remarks, in Panel, Neutrality, The Rights of Shipping and the Use of Force in the

Persian Gulf War (Part I) , 1988 Proc. Am. Soc'y Int'l L. 158, 161, 162; Jules Lobel, The Use of

Force to Terrorist Attacks, 24 Yale J. Int'l L. 537, 541 (1999); Robert W. Tucker, The

Interpretation of War Under Present International Law, 4 Int'l L. Q. 11, 29-30 (1951); see also id., Reprisals and Self-Defense , 66 Am. J. Int’l L. 586 (1972) (States may respond only after being attacked). Recent commentary supports an expanded view of reactive self-defense to include preparations for attack. See, e.g., Christine Gray, International Law and the Use of Force

130, 133 (2d ed. 2004); Mary Ellen O'Connell, Lawful Self-Defense to Terrorism , 63 U. Pitt. L.

12

self-defense include anticipatory self-defense, i.e.

, responding, observing principles of necessity and proportionality before taking the first hit in situations of immediacy, admitting of no alternative?

29

(2) Is there a parallel customary right to self-defense, separate and apart from

Rev. 889, 894 (2002).

29

United Nations, A More Secure World: Our Shared Responsibility: Report of the

Secretary-General's High-Level Panel on Threats, Challenges and Change ¶¶ 188-92 (2004), citing Wolfgang Friedmann, The Changing Structure of International Law 259-60 (1964); Louis

Henkin, How Nations Behave 143-45 (2d ed. 1979), who later changed his view, see n. 28 supra ;

Oscar Schachter, The Right of States to Use Armed Force , 82 Mich. L. Rev. 1620, 1633-34

(1984), says U.N. Charter art. 51 allows a threatened State, "according to long-established international law," to take military action "as long as the threatened attack is imminent , no other means would deflect it and the action is proportionate." However, a State must act in anticipatory self-defense, not just "preemptively." The latter cases should be brought to the U.N.

Security Council for possible action. Article 51 should not be rewritten or reinterpreted.

This approach is in line with those advocating a right of anticipatory individual and collective self-defense based on the Charter and customary law. ILC Draft Articles, supra note

9, art. 25 & cmt. 5, at 194, 196 recognize anticipatory self-defense under the necessity doctrine.

See also Legality of Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons, 1996 I.C.J. 226, 245 (hereinafter

Nuclear Weapons); Nicaragua Case, supra note 9, 1986 I.C.J. at 347 (Schwebel, J., dissenting);

Stanimar A. Alexandrov, Self-Defense Against the Use of Force in International Law 296

(1996); D.W. Bowett, Self-Defence in International Law 187-93 (1958); Charter Commentary, supra note 19, at 1421-27 (representing a change of view from prior editions); Hans Kelsen,

Collective Security Under International Law 27 (Nav. War C. Int'l L. Stud. v. 49, 1957);

Timothy L.H. McCormack, Self-Defense in International Law: The Israeli Raid on the Iraqi

Nuclear Reactor 122-24, 238-39, 253-84, 302 (1996); Myres S. McDougal & Florentino

Feliciano, Law and Minimum World Public Order 232-41 (1961); Walter Gary Sharp, Sr.,

Cyberspace and the Use of Force 33-48 (1999) (real debate is scope of anticipatory self-defense right; responses must be proportional); Jennings & Watts, supra note 5, § 127; Oscar Schachter,

International Law in Theory and Practice 152-55 (1991); Julius Stone, Of Law and Nations:

Between Power Politics and Human Hopes 3 (1974); Ann Van Wynen Thomas & A.J. Thomas,

The Concept of Aggression in International Law 127 (1972); Richard W. Aldrich, How Do You

Know You Are At War in the Information Age?, 35 Hous. J. Int'l L. 223, 231, 248 (2000); Louis

Rene Beres, After the Scud Attacks: Israel, "Palestine," and Anticipatory Self-Defense, 6 Emory

Int'l L. Rev. 71, 75-77 (1992); George Bunn, International Law and the Use of Force in

Peacetime: Do U.S. Ships Have to Take the First Hit?, 39 Nav. War C. Rev. 69-70 (May-June

1986); James H. Doyle, Jr., Computer Networks, Proportionality, and Military Operations , in

Michael N. Schmitt & Brian T. O'Donnell, Computer Network and International Law 147, 151-

54 (Int'l L.Stud., v. 76, 2002); Thomas M. Franck, When, If Ever, May States Deploy Military

Force Without Prior Security Council Authorization?

, 5 Wash. U.J.L. & Pol'y 51, 68 (2001);

13

Charter principles with different contours?

30

(3) Is the right of self-defense, parallel to Charter

Article 2(4), a jus cogens or peremptory norm,

31

trumping treaty and customary law?

32

Christopher Greenwood, Remarks, in Panel, supra note 28, at 158, 160-61; David K. Linnan,

Self-Defense, Necessity and U.N. Collective Security: United States and Other Views, 1991 Duke

J. Comp. & Int'l L. 57, 65-84, 122; Lowe, The Commander's Handbook on the Law of Naval

Operations , in The Law of Naval Operations 127-30 (Horace B. Robertson, Jr. ed. Nav. War C.

Int’l L. Stud. v. 68, 1991) James McHugh, Forcible Self-Help in International Law, 25 Nav. War

C. Rev. 61 (No. 2, 1972); Rein Mullerson & David J. Scheffer, Legal Regulation of the Use of

Force, in Beyond Confrontation: International Law for the Post-Cold War Era 93, 109-14 (Lori

Fisler Damrosch et al. ed. 1995); John F. Murphy, Commentary on Intervention to Combat

Terrorism and Drug Trafficking, in Law and Force, supra note 28, at 241; W. Michael Reisman,

Allocating Competences to Use Coercion in the Post-Cold War World: Practices, Conditions, and Prospects, in id.

25, 45; Horace B. Robertson, Jr., Self-Defense Against Computer Network

Attack under International Law , in Schmitt & O'Donnell, supra , 121, 140; Michael N. Schmitt,

Bellum Americanum: The U.S. View of Twenty-First Century War and Its Possible Implications for the Law of Armed Conflict, 19 Mich. J. Int'l L. 1051, 1071, 1080-83 (1998); Abraham D.

Sofaer, Sixth Annual Waldemar A. Solf Lecture: International Terrorism, the Law, and the

National Defense, 126 Mil. L. Rev. 89, 95 (1989); Robert F. Turner, State Sovereignty,

International Law, and the Use of Force in Countering Low-Intensity Aggression in the Modern

World, in Legal and Moral Constraints on Low-Intensity Conflict 43, 62-80 (Alberto R. Coll et al. eds., Nav. War C. Int'l L. Stud., v. 67, 1995); Claude Humphrey Meredith Waldock, The

Regulation of Force by Individual States in International Law, 81 R.C.A.D.I. 451, 496-99 (1952)

(anticipatory self-defense permissible, as long as principles of necessity, proportionality observed); George K. Walker, Information Warfare and Neutrality , 33 Vand. J. Transnat'l L.

1079, 1122-24 (2000); Ruth Wedgwood, Responding to Terrorism: The Strikes Against bin

Laden, 24 Yale J. Int'l L. 559, 566 (1999). My article, The Lawfulness of Operation Enduring

Freedom's Self-Defense Responses , 37 Valparaiso L. Rev. 489, 536 (2003) says preemption

"seems" equivalent to anticipatory self-defense, citing contradicting views. Jane Gilliland

Dalton, The United States National Security Strategy: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow , 52 Nav.

L. Rev. 60, 68-75 (2005) posits that preemption and anticipatory self-defense are not necessarily different, but that national strategy should adhere to the anticipatory self-defense doctrine. The preemption issue may be resolved after a time of interactive claim and counterclaim, cf.

Myres S.

McDougal, The Hydrogen Bomb Tests , 49 Am. J. Int’l L. 357-58 (1955), as the territorial sea breadth dispute was resolved. Michael P. Scharf, Customary International Law in Times of

Fundamental Change (2013) argues that new rules can come suddenly, e.g.

, after 9/11, where there are game-changer events, i.e.

, “Grotian moments.”

30

Some commentators would so argue. See generally supra note 29.

31

See Vienna Convention, supra note 5, pmbl., arts. 53, 64, 71. Some commentators prefer ius cogens or fundamental norm as the proper phrase. Jus cogens has uncertain contours.

See generally Corten & Klein, supra note 5, at 1-11, 1224-35, 1455-80, 1612-25; Crawford,

14

supra note 5, at 594-602 (jus cogens' content uncertain); T.O. Elias, The Modern Law of Treaties

177-87 (1974) (same); Jennings & Watts, supra note 5, §§ 2, 642, 653 (same); McNair, supra note 5, at 214-15 (same); Restatement, supra note 5, §§ 102 r.n. 6, 323 cmt. b, 331(2), 338(2)

(same); Shabtai Rosenne, Developments in the Law of Treaties 1945-1986, at 281-88 (1989);

Sinclair, supra note 5, at 17-18, 218-26 (Vienna Convention rules considered progressive development in 1984); Grigorii I. Tunkin, Theory of International Law 98 (William E. Butler trans. 1974); Levan Alexidze, Legal Nature of Jus Cogens in Contemporary Law , 172

R.C.A.D.I. 219, 262-63 (1981); John N. Hazard, Soviet Tactics in International Lawmaking , 7

Denv. J. Int'l L. & Pol. 9, 25-29 (1977); Jimenez de Arechaga, International Law in the Last

Third of a Century, 159 R.C.A.D.I. 9, 64-67 (1978); Georg Schwarzenberger, International Jus

Cogens?

, 43 Tex. L. Rev. 455 (1978) (jus cogens nonexistent for self-defense, any other purpose); Dinah Shelton, Normative Hierarchy in International Law , 100 Am. J. Int’l L. 291

(2006) (current analysis); Mark Weisburd, The Emptiness of the Concept of Jus Cogens, As

Illustrated by the War in Bosnia-Herzegovina, 17 Mich. J. Int'l L. 1 (1995). An International

Law Commission study acknowledged primacy of U.N. Charter art. 103-based law and jus cogens but declined to catalogue what are jus cogens norms. International Law Commission,

Report on Its Fifty-Seventh Session (May 2-June 3 and July 11-August 5, 2005), UN GAOR,

60th Sess., Supp. No. 10, pp. 221-25, UN Doc. A/60/10 (2005); see also Michael J. Matheson,

The Fifty-Seventh Session of the International Law Commission , 100 Am. J. Int’l L. 416, 422

(2006).

32 Nuclear Weapons, supra note 29, 1996 I.C.J. at 245; Nicaragua Case, supra note 9,

1986 I.C.J. at 100-01 (U.N. Charter art. 2[4] approaches jus cogens status); see also ILC Draft

Articles, supra note 9, art. 50 & cmts. ¶¶ 1-5, in 2001 ILC Rep., supra note 25, at 247-49;

("fundamental substantive obligations"); Jennings & Watts, supra note 5, § 2 (U.N. Charter art.

2[4] a fundamental norm); Restatement, supra note 5, §§ 102, cmts. h, k; 905(2) & cmt. g

(same); Carin Kaghan, Jus Cogens and the Inherent Right of Self-Defense, 3 ILSA J. Int’l &

Comp. L. 767, 823-27 (1997) (U.N. Charter art. 51 represents jus cogens norm); 2001 ILC Rep., supra at 177-80, art. 21 & cmts., resolving the issue of conflict between UN Charter arts. 2(4) and 51 by saying that no art. 2(4) issues arise if there is a lawful self-defense claim, appears to give art. 51 the same status as art. 2(4). Kaghan’s analysis is logical; if a State’s right to territorial integrity under U.N. Charter art. 2(4) has jus cogens status, that State must have a jus cogens right to defend its territory, subject to rules of necessity and proportionality and, in the case of anticipatory self-defense, admitting of no other alternative. The International Court of

Justice may have stopped short of according Article 2(4) jus cogens status because I.C.J. Statute art. 38(1), which does not list jus cogens as a source, may have limited the Court’s analysis.

Armed Activities on Terr. of Congo (Dem. Rep. of Congo v. Rwanda), 2006 I.C.J. 3, 29-30, 49-

50 (jurisdiction, admissibility of application) (hereinafter 2006 Congo Case) held a jus cogens violation allegation was not enough to deprive the Court of jurisdiction, preliminarily stating that

Convention on Prevention & Punishment of Crime of Genocide, Dec. 9, 1948, T.I.A.S. No. — ,

78 U.N.T.S. 277 represented erga omnes obligations; see also Application of Convention on

Prevention & Punishment of Crime of Genocide (Bosnia & Herzegovina v. Serbia &

15

Implications for the law of the sea,

33

and other treaties governing admiralty practice, is that the

Charter-based and customary rights of self-defense trump standards in those treaties and the customary law of the sea.

34

As noted above, how individual countries, collective self-defense

Montenegro), 2007 I.C.J. 47, 110-11 citing 2006 Congo Case, supra . Vienna Convention, supra note 5, art. 53 (declaring jus cogens standards) was among other treaties 2006 Congo Case, supra cited. Also citing Nicaragua and Nuclear Weapons Cases, supra , Shelton, supra note 31 at 305-06 says 2006 Congo Case, supra is the first I.C.J. case to recognize jus cogens, but its holding seems not quite the same as ruling on an issue and applying jus cogens. The case compromis included the Vienna Convention, supra , which raises jus cogens issues that the Court could have decided under that law as well as traditional sources. I.C.J. Statute arts. 36, 38, 59.

Thus the issue technically remains whether the Court will apply jus cogens as a separate trumping norm, or whether it will apply jus cogens as stronger custom among competing primary sources – treaties, custom, general principles – under id. 38(1), or choose not to apply it at all.

33 I respectfully dissent from Churchill & Lowe, supra note 7, at 6, who argue that jus cogens has little relevance for the law of the sea. This article explains why.

34 UNCLOS, supra note 3, arts. 88, 301 acknowledge Charter primacy; see also Churchill

& Lowe, supra note 7, at 170, 411, 430-31; 3 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

1982: A Commentary ¶¶ 88.1-88.7(d) (Satya N. Nandan & Shabtai Rosenne vol. eds., Neal R.

Grandy ass’t ed. 1995) (hereinafter 3 Commentary); 5 id. ¶¶ 301.1-301.6 (Myron H. Nordquist ed.-in-chief, Shabtai Rosenne & Louis B. Sohn vol. eds. 1989) (hereinafter 5 Commentary);

Restatement, supra note 5, § 521 cmt. b; Donald R. Rothwell & Tim Stephens, The International

Law of the Sea 266 (2010); supra note 16 and accompanying text. The “peaceful purposes” language of UNCLOS, supra , art. 88 must be read in the context of id. art. 87's “other rules” exception for the law of armed conflict, and the primacy of the inherent right to individual and collective self-defense, see U.N. Charter arts. 51, 103; supra notes 6, 16, 20 and accompanying text. Tarros S.p.a. v. United States, 2014 A.M.C. at 77-78, noted plaintiff’s citing UNCLOS, supra , arts. 87-88 for the right of freedom of high seas navigation and that the high seas are reserved for peaceful purposes. What was not mentioned was id. art. 87's “other rules” exception, or the supremacy of Charter law through Security Council Resolutions 1970, 1973, supra note 14, under U.N. Charter art. 103, or that, at least insofar as public international law issues are concerned, the United States considers the UNCLOS articles related to navigation to represent customary international law. See President Ronald Reagan, Statement of United States

Oceans Policy, Mar. 10, 1983, 19 Weekly Comp. Pres. Doc. 383 (Mar. 14, 1983) (hereinafter

Reagan Statement). However, for U.S. courts, the High Seas Convention, supra note 3, with its freedom of navigation and “other rules” provisions in Article 2, would apply; The Pacquete

Habana, 175 U.S. at 677, 700 (1900), whose principles Sosa v. Alvarez-Machain, 542 U.S. 692,

734 (2004) repeats, declared that U.S. courts may recognize and apply customary international law if there is no controlling precedent, treaty, federal statute, or executive action. The Habana rule for treaties is also subject to the principle that the treaty must be self-executing. Cf. Medellin

16

organizations like NATO and coalitions, as well as naval forces and units, exercise the right may be conditioned by States’ national directives, which was what happened in the Libya crisis.

35

B. The law of armed conflict at sea and admiralty law

In armed conflict situations not governed by mandatory Council decisions or self-defense situations trumping other rules,

36

the law of armed conflict may oust the general law of the sea and agreements subordinate to it

37

through the “other rules” clauses.

38

The International Law v. Texas, 552 U.S. 491, 503-23 (2007). If a treaty is non-self-executing and Congress has enacted implementing statutes, the legislation must be followed. All of this was beside the point for the Tarros decision; the court correctly held, 2014 A.M.C. at 77-78, that the claim fell under the Public Vessels Act, supra note 17, and the Suits in Admiralty Act, 46 U.S.C. §§ 30901-18

(2012). Federal legislation like this is, of course, an exception to applying customary international law rules, e.g.

, those from UNCLOS, supra . See Sosa, supra ; Habana , supra.

35 See supra notes 8-24 and accompanying text.

36 See supra notes 15, 19, 31 and accompanying text.

37 UNCLOS, supra note 3, arts. 311(2)-311(6), with certain exceptions, e.g.

, express authority within UNCLOS to conclude subordinate agreements permitted or preserved by

UNCLOS, declares that other subordinate agreements may not alter other States’ rights and obligations under the Convention. See also Churchill & Lowe, supra note 7, at 20, 125, 238,

292; 5 Commentary, supra note 34, ¶¶ 311.1-311.11.

38 See supra notes 3, 7 and accompanying text. The ensuing analysis assumes the law of the sea and the law of international armed conflict at sea, as they relate to admiralty practice, apply. There are variants on the theme, some of which are discussed below, e.g., human rights law, infra notes 98-106 and accompanying text, and international environmental law, infra notes

70-84 and accompanying text. There are others. Consider, e.g., riverine warfare and shipping losses on the rivers in an international armed conflict, the situation (at least according to the U.S.

view) of the Vietnam War and attacks by North Vietnam-related forces on South Vietnam river traffic. Inland lakes pose similar problems, e.g.

, naval campaigns on the Great Lakes during the

War of 1812. Nor does the analysis consider differences, if any, of rules for non-international armed conflicts, e.g.

, in, the U.S. Civil War, Confederate blockade runner interdiction by the

U.S. Navy or Confederate high seas interdictions of Union merchant shipping. It does not account for riverine war rules in non-international armed conflicts, e.g., Civil War campaigns on

U.S. western rivers, notably the Mississippi. It does not take into account situations where a conflict has can have international dimensions, such as the U.S. self-defense response after 9/11, the subsequent involvement of NATO and other forces aligned with the United States in

17

Association (American Branch) project on law of the sea definitions illustrates cases where terms in the law of the sea and the law of armed conflict may have quite different meanings.

39

Besides terms, there are practices under the law of the sea that are similar to, but different in concept from, the law of armed conflict at sea. For example, approach and visit may be appropriate under the law of the sea for some situations, e.g.

, drug runners; the concept of visit and search is a practice incident to checking for war contraband.

40 There are law of armed conflict principles that have no law of the sea counterpart, e.g.

, belligerents’ customary rights to exclude merchant shipping from an immediate area of naval operations.

41 Sometimes armed conflict rules are virtually the same as the law of the sea rules; e.g.

, the definition of a warship 42

Afghanistan in the resulting ground and air campaigns, and a parallel non-international armed conflict between Afghanistan’s Northern Alliance and the Taliban government. For an early account of this conflict, see Walker, The Lawfulness, supra note 29.

39 See Walker, Definitions, supra note 4, at 271-72.

40 Compare C. John Colombos, The International Law of the Sea § 334 (6th ed. 1967) with id. ch. 20; Thomas & Duncan, supra note 9, ¶¶ 3.4-3.8 with id. ¶¶ 7.6-7.6.2; see also 2

O’Connell, supra note 7, at 801-03; San Remo Manual, supra note 15, ¶¶ 118-24; UK Manual, supra note 9, ¶¶ 13.91-13.97. Two more current oceans law sources blur the distinction between approach and visit under the law of the sea and visit and search under the law of armed conflict.

Churchill & Lowe, supra note 7, at 210-13, 218, 423; Rothwell & Stephens, supra note 34, at

156, 165-66, 432.

7.8.1.

41 San Remo Manual, supra note 15, ¶ 108; Thomas & Duncan, supra note 9, ¶¶ 7.8-

42 Compare UNCLOS, supra note 3, art. 29; High Seas Convention, supra note 3, art.

8(2); with Hague Convention (VII) Relating to the Conversion of Merchant Ships into War-

Ships, arts. 2-3, Oct. 18, 1907, 205 Consol. T.S. 319 (hereinafter Hague VII); see also 2 United

Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982: A Commentary ¶¶ 29.1-29.8(b) (Satya N.

Nandan & Shabtai Rosenne vol. eds., Neal R. Grandy ass’t ed. 1993) (hereinafter 2

Commentary); Jennings & Watts, supra note 5, §§ 560–61; Rothwell & Stephens, supra note 34, at 265-66; Thomas & Duncan, supra note 9, ¶¶ 2.1.1-2.1.3; in Gabriella Venturini, Commentary , in Natalino Ronzitti, The Law of Naval Warfare 120, 122 (1988) (Hague VII, supra arts. 2-3 customary law). Although many States ratified Hague VII, supra , the United States did not.

18

and the requirement that, commensurate with the safety of a succoring ship and its crew, there is an obligation to rescue those in peril on the sea.

43

(It is also a complete defense under treaties

Signatures, Accessions and Ratifications, Dietrich Schindler & Jiri Toman, The Laws of Armed

Conflicts 1068-70 (4th ed. 2004). Due to the similarity of the Hague VII definition and those in the High Seas Convention and UNCLOS, the principle of treaty succession for Hague

Convention parties, and acceptance of the High Seas Convention and UNCLOS’ navigational articles as customary norms, it is safe to say that the same definition applies during peace and war. The same definition of a warship applies whether it is subject to the law of the sea or is in inland waters. ARA Libertad (Argentina v. Ghana), (No. 20) (Argentina v. Ghana), Request for

Provisional Measures (ITLOS, Dec. 15, 2012), available at http://www.ITLOS.ORG; see also

David P. Stewart, Convention on the Law of the Sea – Warship Immunity – Scope of

Applicability of Convention – Provisional Measures – Definition of Warship – Arbitral Decision ,

107 Am. J. Int’l L. 404 (2012). The attempted Libertad seizure was part of worldwide creditor efforts to seize property of the Republic of Argentina in a sovereign debt case. Brent Kendall &

Shane Romio, Argentina Loses Debt Ruling , Wall St. J., Oct. 8, 2013, at C3, reporting Supreme

Court certiorari denial in RML Capital, Ltd. v. Republic of Argentina, 727 F.3d 230 (2d Cir.

2013), cert. denied , 134 S.Ct. 201 (2014).

43 This rule seems not to have been followed in one case during Libyan interdiction operations. Rose George, Ninety Percent of Everything: Inside Shipping, the Invisible Industry that Puts Clothes on Your Back, Gas in Your Car, and Food on Your Plate 90 (2013). Compare

UNCLOS, supra note 3, arts. 98(1)(a), 98(1)(b); High Seas Convention, supra note 3, arts.

12(1)(a), 12(1)(b); International Convention for Unification of Certain Rules of Law with

Respect to Assistance and Salvage at Sea, arts. 11, 14, Sept. 23, 1910, 37 Stat. 1658 (hereinafter

1910 Salvage Convention) (not applicable to warships), being replaced by International

Convention on Salvage, arts. 4, 10, Apr. 28, 1989, T.I.A.S. — , U.S. Treaty Doc. 102-12 (not applicable to warships unless State party applies Convention to them) (hereinafter 1989 Salvage

Convention); International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, Regs. 2, 10, ch. V, Nov. 1,

1974, 32 U.S.T. 47, 1184 U.N.T.S. 2, with Convention (II) for the Amelioration of the

Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea, arts. 12, 18,

Aug. 12, 1949, 6 U.S.T. 3217, 75 U.N.T.S. 85 (hereinafter Second Convention); see also id. art.

5 (neutrals must apply by analogy id .’s provisions to wounded, sick, shipwrecked, armed forces medical personnel, armed forces chaplains of parties to a conflict, and the dead found at sea);

Hague Convention (X) for the Adaptation to Maritime Warfare of the Principles of the Geneva

Convention, art. 16, Oct. 17, 1907, 36 Stat. 2371 (hereinafter Hague X), superseded by Second

Convention, supra , art. 33); 3 Commentary, supra note 34, ¶¶ 98.1, 98.11(g); (treaties’ use of “at sea” means they also apply in the territorial sea); see also Colombos, supra note 40, § 369;

Jennings & Watts, supra note 4, § 298; 2 Oppenheim, supra note 5, §§ 204-05; 2 Jean S. Pictet,

Commentary 41-45, 86-90 (1960); Rothwell & Stephens, supra note 34, at 161-62; Thomas &

Duncan, supra note 9, ¶¶ 3.2.1-3.2.1.2; L.R. Penna, Commentary, in Ronzitti, supra note 42, at

534. George, supra at 211-19 recounts a 2007 containership rescue of survivors of a

19

and other laws governing carriage of goods by sea for deviating to save life or property at sea.

44

)

There are other situations where a proclaimed sea area under the law of armed conflict may be the same, or close to the same area proclaimed under the law of the sea, an example being maritime exclusion zones whose borders may be close to the same as, or different from, e.g.

, claimed a belligerent’s claimed exclusive economic zone.

45 In these circumstances, and others in the maritime law of armed conflict, law of armed conflict rules trump the otherwise applicable law of the sea. Moreover, common sense would suggest avoiding a combat area if feasible, as the tanker Hercules and her owner and charterer discovered during the 1982 Falklands/Malvinas

War.

46 (An example of the mix of these two bodies of law might be a situation where merchantman sinking and other ships that disregarded their duty. While I was aboard U.S.S.

Tweedy (DE-532), we picked up two boatloads of Cuban refugee families adrift in the Gulf

Stream in 1962; if we had not happened upon them (there was only a fuzzy radar signal), they would have drifted until they died. Loss of hundreds of refugees in Italy’s Lampedusa Island territorial sea prompted European Union action to improve Mediterranean Sea rescue patrols.

James Kanter & Gaia Piangiani, After Migrant Deaths, European Official Urges More Patrols at

Sea , N.Y. Times, Oct. 9, 2013, A8. Italian authorities arrested some connected with the human trafficking operation. Deborah Hall, Italy Arrests Alleged Organizer in Ship Disaster , Wall St.

J., Nov. 9-10, 2013, at A8. Warm weather prompts more attempts. Eric Sylvers et al., Warm

Weather Spurs Tide of Migrants , id.

, Apr. 12-13, 2014, A7.

44 See infra note 56 and accompanying text.

45 UNCLOS, supra note 3, arts. 55-75; San Remo Manual, supra note 15, ¶¶ 105-07 & cmts.; Thomas & Duncan, supra note 9, ¶¶ 1.5.2, 7.9; see also Churchill & Lowe, supra note 7, ch. 9; 2 Commentary, supra note 42, Pt. V; Crawford, supra note 5, at 274-80, 293-94; Jennings

& Watts, supra note 5, §§ 327-47; Restatement, supra note 5, §§ 511(d), 514; Rothwell &

Stephens, supra note 34, at 82-97. During the 1982 Falklands/Malvinas War, exclusion zones around the islands were close to, if not the same as, areas that could be claimed as an exclusive economic zone under the law of the sea. See generally The Tanker War, supra note 21, at 129 and sources cited.

46

See generally Argentine Republic v. Amerada Hess Shipping Corp., 488 U.S. 428, 433-

39 (1989), rev’ing 839 F.2d 421, 423 (2d Cir. 1987) (Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act

(hereinafter FSIA), 28 U.S.C. §§ 1330, 1602-11 [2012] the sole basis for obtaining jurisdiction over a foreign State in U.S. federal courts).

20

merchantmen come upon people in the water while vacating a wartime naval operations area.

The primary rescue obligation would lie with naval forces, not the merchantmen, which must leave the area.) A peripheral problem for armed conflict at sea is the status of the 1907 Hague

Conventions on sea warfare. One, covering the wounded, sick and shipwrecked, has been superseded; 47 others may live on as treaty law or in whole or part by customary acceptance of some or all of their terms.

48

C. Vessel seizure or diversion during armed conflict

Prize law, for which U.S. District Courts have exclusive jurisdiction, 49 remains an

47 Second Convention, supra note 43, art. 33, superseding inter alia Hague X, supra note

43; see also 2 Pictet, supra note 43, at 187-89.

48 Others from the 1907 Conference were Convention (VI) Relating to the Status of

Enemy Merchant Ships at the Outbreak of Hostilities, Oct. 18, 1907, 205 Consol. T.S. 305;

Hague VII, supra note 42; Convention (VIII) Relative to the Laying of Automatic Submarine

Contact Mines, Oct. 18, 1907, 36 Stat. 2332; Convention (IX) Concerning Bombardment by

Naval Forces in Time of War, Oct. 18, 1907, 36 Stat. 2351; Convention (XI) Relative to Certain

Restrictions with Regard to the Exercise of the Right of Capture in Naval War, Oct. 18, 1907, 36

Stat. 2396 (hereinafter Hague XI); see also Convention (XII) Relative to the Creation of an

International Prize Court, Oct. 18, 1907 (hereinafter Hague XII), never ratified, Schindler &

Toman, supra note 42, at 1093. Some provisions are now in desuetude; others may survive through customary acceptance or treaty succession principles; sometimes later customary practice has superseded them. See generally Andrea de Guttry, Commentary , in Ronzitti, supra note 42, at 102; Howard S. Levie, Commentary, in id. 140; Horace B. Robertson, Jr.,

Commentary , in id.

161; I.A. Shearer, Commentary , in id. 183; supra note 6 and accompanying text.

49 28 U.S.C. § 1333(2) (2012). There have been no U.S. prize cases reported since

World War II, see The Europa, 1948 A.M.C. 1454 (S.D.N.Y. 1948); The Wilhelmina, 78 F.Supp.

57 (W.D. Wash. 1942) (no prize declared). If a ship chased for prize boarding and seizure tries to scuttle, and is successfully salvaged, the Navy crew may be entitled to salvage bounty. The

Odenwald, 71 F.Supp. 314, 1947 A.M.C. 666 (D.P.R. 1947), modified sub nom.

Hamburg-

American Line v. United States, 168 F.2d 47 (1st Cir. 1948). Prize money goes to the U.S.

Treasury, 10 U.S.C. § 7668 (2012), where prize sale proceeds in The Pacquete Habana, 175 U.S.

677 (1900), would have gone; however, Habana held the seized boats were not lawful prize.

21

international issue.

50

A narrow issue is whether traditional prize rules apply in diversion situations,

51

and particularly in a U.N.-mandated diversion,

52

a method for examination of contraband today and may qualify for the restraint of princes exception, if not the war exception, in carriage of goods claims and other situations.

53 Undoubtedly this issue will arise in claims, litigation and arbitration in the wake of the Libya crisis; Tarros may be the first of many of these cases.

54

D. Ocean bills of lading

Exceptions under treaties and national legislation governing ocean bills of lading, e.g.

, acts of war, acts of public enemies, arrest or restraint of princes, rulers or people, or seizure

50 See, e.g.

, The Tanker War, supra note 21, at 68 (1988 Iran prize law during 1980-88 conflict). Hague XII, supra note 48, would have created an international appellate prize court; no

State ratified it.

51 In diversion operations, merchantmen are sent to, e.g.

, a sheltered harbor or bay of an ally that is safer than the high seas for onboard inspection. Diversion is an acceptable alternative today. See generally San Remo Manual, supra note 15, ¶¶ 51, 52, 121, 138, 152. Coalition forces diverted merchantmen during the 1990-91 campaign against Iraq. See generally Walker,

The Crisis, supra note 24, at 35.

52 The situation in the 2011 Libya crisis, as in 1990-91 in the Persian Gulf. See supra notes 8-17 and accompanying text.

53 See infra notes 55, 64, 127, 145 and accompanying text.

54 In Tarros S.p.a. v. United States, 2014 A.M.C. at 53-55, the owner claimed the Vento carried “medical equipment, medicine, first aid supplies, and food stuffs,” presumably destined for the civil population and therefore subject to exemption from seizure under the law of armed conflict. Nevertheless, Vento was directed to proceed to an Italian port, presumably for cargo inspection to be certain that this was, in fact, the cargo as declared. This has been typical (and lawful) interdiction, diversion and inspection procedure. See generally San Remo Manual, supra note 15, ¶¶ 47(c)(ii), 118-24; Thomas & Duncan, supra note 9, ¶ 7.6.1; see also supra notes 51-

52 and accompanying text.

22

under legal process, may apply in armed conflict situations.

55

Deviation from course to save, or attempting to save, life or property at sea is a defense to claims against a carrier or the ship.

56

Another provision makes carriers liable for “unreasonable” deviation,

57

which might happen in situations like the Libya crisis if armed forces bar entry into the port(s) designated in a bill of lading or requisition a ship.

58 Bills of lading may have a liberties clause, allowing a carrier

55

International Convention for the Unification of Certain Rules of Law Relating to Bills of Lading, arts. 4(2)(e)-4(2)(g), Aug. 25, 1924, 51 Stat. 233, 120 L.N.T.S. 157 (hereinafter

Hague Rules); amended by Protocol to Amend the International Convention for the Unification of Certain Rules of Law Relating to Bills of Lading of August 24, 1924, Feb. 23, 1968, 1412

U.N.T.S. 121 with provisions not relevant to this analysis (hereinafter Visby Amendments, also sometimes referred to collectively with Hague Rules, supra as Hague-Visby Rules); Protocol

Amending the International Convention for the Unification of Certain Rules of Law Relating to

Bills of Lading of August 25, 1924, as Amended by Protocol of February 23, 1968, Dec. 21,

1979, 1412 U.N.T.S. 121, whose amendments are not relevant to this analysis; see also United

Nations Convention on the Carriage of Goods by Sea, Mar. 31, 1978, 1695 U.N.T.S. 3

(hereinafter Hamburg Rules); United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International

Carriage of Goods Wholly or Partly by Sea, art. 17(3)(c), Oct. 18, 2009, G.A. Res. 63/122, U.N.

Doc. A/RES/63/122 (2009) (also known as the Rotterdam Rules, not in force); Carriage of

Goods by Sea Act, 46 U.S.C.A. Note, reprinting 46 U.S.C.A. §§ 1304((2)(e)-1304(2)(g) (2012)

(hereinafter COGSA); Harter Act, 46 U.S.C.A. §§ 30706(b)(2)-30706(b)(4) (2012). The United

States is a Hague Rules, supra party, see TIF, supra note 7, at 423; documents involving U.S.

parties may incorporate later treaties by reference as contract terms. See Norfolk S. Ry. v.

Kirby, 543 U.S. 14, 23-25 (2004); Thomas J. Schoenbaum & Jessica McClellan, Admiralty and

Maritime Law § 8-8 (5th ed. 2011).

56 Hague Rules, supra note 55, arts. 4(2)( l ), 4(4); Hamburg Rules, supra note 55, art.

5(6); Rotterdam Rules, supra note 55, arts. 17(3)( l ), 17(3)(m); COGSA, supra note 55, 46

U.S.C.A. Note, §§ 4(2)( l ), 4(4) (2012); Harter Act, supra note 55, 46 U.S.C.A. § 30706(b)(8)

(2012); see also Schoenbaum & McClellan, supra note 55, § 7-34. Rotterdam Rules, supra art.

3(n) also allows reasonable measures to avoid or attempt to avoid damage to the environment.

57 Hague Rules, supra note 55, art. 4(4); Hamburg Rules, supra note 55, art. 5(6); compare Rotterdam Rules, supra note 55, art. 24; COGSA, supra note 55, 46 U.S.C.A. Note §

1304(4) (2012); see also Schoenbaum & McClellan, supra note 55, § 7-34.

58

This was the situation in Sedco, Inc. v. S.S. Sthrathewe, 620 F.Supp. 120, 121

(S.D.N.Y.), aff’d , 800 F.2d 27, 30-33 (2d Cir. 1986); see also Keith W. Heard, Sedco v. M/V

Strathewe: An Interesting Case Indeed , 7 Benedict’s L. Bull. 190, 191-92 (2009).

23

flexibility in offloading cargo at destination ports.

59

Although treaties and national legislation are fairly uniform in language for these exceptions to liability, will new situations in the Charter era fare the same way in the courts and before arbitrators? Whether the result will be the same as the “old law” for these new situations, the admiralty lawyer must be familiar with international law lurking in the background of a claim and defenses to it. The only treaty binding the United States, the 1924 Brussels Convention (the

Hague Rules), presents another interesting application of international law. Congress passed legislation implementing the Brussels Convention before the U.S. Senate gave advice and consent to the treaty. The result was an understanding appended to the U.S. ratification, that as between rules in the Convention and the earlier federal legislation, the federal statute governs.

60

This understanding 61 overrides the usual U.S. construction rule that as between federal legislation and an international agreement, the later in time governs.

62 Thus admiralty proctors

59 See Sedco , 620 F.Supp. at 121, aff’d , 800 F.2d at 29 (2d Cir. 1986) (ship requisitioned for 1982 Falklands/Malvinas War).

60 Hague Rules, supra note 55, 51 Stat. 233. See generally George K. Walker,

Professionals’ Definitions and States’ Interpretative Declarations (Understandings, Statements, or Declarations) for the 1982 Law of the Sea Convention , 21 Emory Int’l L. Rev. 461 (2007)

(proposing rules for declarations like reservations rules under Vienna Convention, supra note 5).

61 Counsel examining TIF, supra note 7, at 423 would have been alerted to the U.S.

understandings, published in 51 Stat. 233, and the U.S. rejection of Kuwait’s reservation to the treaty, which would lead to examination of the complex law of reservations to multilateral agreements. See generally Walker, Professionals’, supra note 60 for analysis in the context of interpretative statements like the U.S. understanding to the same treaty.

62 Breard v. Greene, 523 U.S. 371, 375 (1998); Whitney v. Robertson, 124 U.S. 190, 194

(1888). Another example, prioritizing earlier treaties over later statutes, is in the FSIA, supra note 46, 28 U.S.C. § 1604 (2012), preserving other treaty rules on governmental immunity.

Compare Kalamazoo Spice Extraction Co. v. Provisional Mil. Gov’t of Socialist Ethiopia, 729

F.2d 422, 425-28 (6th Cir. 1984) (treaty governed immunity, not § 1604) with DeCsepel v.

Republic of Hungary, 714 F.3d 591, 601-03 (D.C. Cir. 2013) (earlier treaties did not).

24

must understand these and other aspects of the law of treaties. The Vento interdiction during the

Libya crisis illustrates the problem.

63

E. Chartering ships

Charter party exceptions for e.g.

, enemy action; restraint of princes, rulers and people,

64 or case law exceptions to performance like frustration of contract,

65

may apply in armed conflict situations. While the prior law, based on pre-Charter cases, may be fairly straightforward, how do these exceptions fare under the relatively new law since 1945? Presumably the result would be the same in similar situations, but what about diversions like those that occurred off Libya?

66

Clauses in some charters may cover these situations, too.

67

F. Marine insurance

Ocean marine insurance claims may also raise these kinds of issues, e.g.

, war risk or

63 See Tarros S.p.a. v. United States, 2014 A.M.C. at 53-55.

64 See, e.g.

, Association of Ship Brokers and Agents (U.S.A.), Inc., New York Produce

Exchange Time Charter Party Form (NYPE 93) ¶ 21, Form 7-12C, 2B Benedict on Admiralty

(Le Roy Lambert ed.-in-chief, 7th ed. 2012) (hereinafter NYPE 93). See also id. ¶¶ 31(a) (clause paramount incorporating by reference COGSA, supra note 55; Hague Rules, supra note 55;

Hague-Visby Rules, supra note 55, “as applicable, or any national legislation as may manditorily apply . . . ”), 31(e)( I), (prohibition on shipping contraband, provisions governing war, warlike operations, hostilities), 31(iii), 31(iv), 32 (cancellation clause for war, declared or not).

65 The Claveresk, 264 Fed. 276, 283 (2d Cir. 1920); see also Restatement (Second) of

Contracts §§ 261, 264 (1979).

66 The warship interception of Vento in Tarros S.p.a. v. United States, 2014 A.M.C. at

53-55, might raise contract frustration issues for cargo and other interests; it was not an issue for the parties in id.

, however. See also R. Glenn Bauer, Effects of War on Charter Parties , 13

Tulane Mar. L.J. 13 (1988).

67

See, e.g., NYPE 93, supra note 64, clauses. Arbitration resolves most charter disputes, but arbitral awards are often not published; a corpus of jurisprudence for these kinds of conflicts may be years away. See also Schoenbaum & McClellan, supra note 55, § 14-15, at 943.

25

terrorist attacks, and excluding coverage because of these threats.

68

However, private companies or governments sell war or terrorism risk insurance. Premiums can be high.

69

How marine insurance will or has figured in Libya crisis - related claims like those involved in Tarros is not clear, but these may arise through coverage or subrogation suits in the future. Nothing moves on the water without insurance.

G. Environmental degradation

Environmental pollution can involve international law issues. After the Torrey Canyon

68 Marine Insurance Act, 1906, 6 Edw. 7, ch. 41, § 3 (“‘Maritime perils’ means the perils consequent on, or incidental to, the navigation of the sea, that is to say, . . . war perils, . . .

captures, seizures, restraints, and detainments of princes and peoples, and any other perils, either of the like kind or which may be designated by the policy”); American Institute of Marine

Underwriters, Cargo Clauses 2004 – All Risks (2004) (“1. Average Terms. ‘All Risks.’ The following average terms shall apply: A. Unless otherwise specified below, this policy insures against ‘All Risks’ of physical loss or damage from any external cause irrespective of percentage, but excluding nevertheless the risks of War, . . . Seizure, Detention and other risks excluded by the Nuclear/Radioactive Contamination Exclusions Clause, the F.C. & S. (Free of