The importance of certification to the paralegal profession

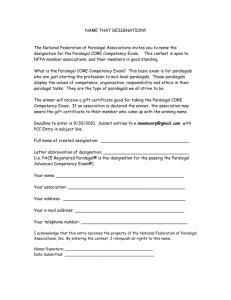

advertisement

The importance of certification to the paralegal profession The paralegal profession is a serious profession, and it should be recognized as such. Having a proper system in place to validate the qualifications and competence of paralegals is the first step to bringing public recognition to the profession. After some forty years of existence of the profession, it is regrettable that a lot of attorneys, and more so their clients, are still unable to tell the difference between a paralegal and a legal secretary, though both are equally important to the delivery of legal services. The lack of a conceptual distinction between the two is undesirable because it leads to the under-utilization of the capabilities of the paralegal, makes it more difficult to justify the paralegal hours billed to the client, and makes the overall provision of legal services less cost-effective. With a publicly recognized, welladministered, and rigorous certification system, we are one step closer to educating attorneys and the public about the distinctive and valuable role paralegals play. A paralegal is qualified by education and experience to perform, under an attorney's supervision, substantive legal tasks which require a good understanding of legal principles and procedures. While it is commendable that many legal secretaries over time evolve into paralegals after acquiring the "education and experience" that is commensurate with the definition of a paralegal, an employer who needs someone to perform "substantive legal work" should hire an attorney or a paralegal, not a legal secretary. Having a certification system for paralegals will make employers' hiring decisions easier, and prospective paralegals' entry into the field easier. It also makes it easier for courts to award fees for paralegals' work. Certification can be administered by state bars, state paralegal associations, or national paralegal associations; it can be voluntary or mandatory. Currently in Texas, paralegal certification is voluntary and is offered by national paralegal associations such as NALA or NFPA. Certification in specialized areas of law is offered through the State Bar of Texas. Common to all certification programs are built-in features to ensure a good level of competence. First, the credential of being "certified" comes only after passing rigorous examinations that test the skills and knowledge that are required to perform substantive legal work. Second, recertification requires completing a minimum number of CLE hours, which compels the paralegal to update his or her knowledge and skills in the field. Third, the "certified" paralegal is expected to conduct him-or-herself in compliance with the ethical standards of the legal profession. Invariably, there is an ethics component to the examinations, and a minimum ethics CLE requirement to remain certified. The certifying board can also revoke the credential if a paralegal is convicted of felony, or found to have violated the code of ethics and professional conduct endorsed by the board. That certifying boards have the authority to sanction certified paralegals blurs the concepts of certification and regulation. In the absence of a licensing regime for paralegals in the majority of states, including Texas, the paralegal profession is basically not regulated by state agencies or the state bar. Voluntary regulation exists in the form of voluntary membership of paralegal associations, which usually require members to possess the minimum requisite education and to adhere to a defined set of professional conduct, but do not vet the competence of each member. Certification, with the institutionalized mechanisms described above, serves as a middle ground between voluntary regulation through membership of organizations and mandatory licensing of all who call themselves paralegals. Certification, on the other hand, can only serve as an indicator and not a foolproof guarantee of competence. As with all professionals, a properly certified paralegal can still be sloppy in performing substantive legal tasks, bring undesirable attitudes to the workplace, or engage in behavior that borders the unethical. Occasionally, the court will reprimand the inappropriate behavior; but most of the time disciplinary matters will be left to the supervising attorney or the firm. In general, however, a paralegal who bothers to go through the certification process and remains certified tends to be motivated and committed to the profession. The paralegal profession has come a long way since the early 1970s. Now the trend is towards specialization. Certification in specialized practice areas gives rise to higher expectations of the knowledge and competence of the "specialist" thus certified. The implications on the paralegal profession can be profound. For example, it is not impossible to envisage eventually a movement towards relaxing the definition of "unauthorized practice of law" (UPL), which is strictly construed at present. Specialized paralegals may one day be able to independently provide limited legal services in limited areas, which may help lower the cost and increase the overall accessibility of legal services. Whether certification should be mandatory, or made prerequisite to entry into the profession, is beyond the scope of this short essay. Suffice it to say that certification raises the profile of the paralegal profession by providing recognizable parameters for assuring the qualification and competence of individual paralegals. It helps streamline hiring decisions, shape public expectations of, and build public confidence in, the profession.