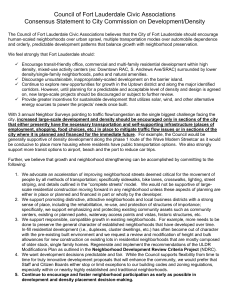

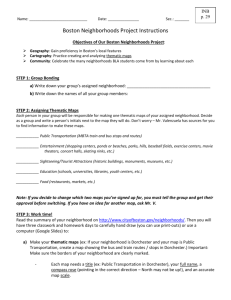

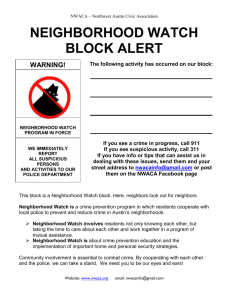

Building Successful Neighborhoods

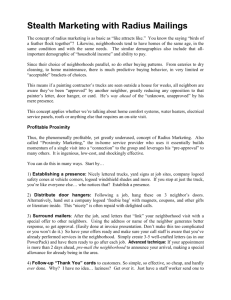

advertisement