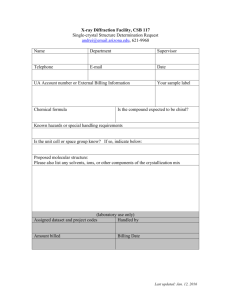

billing field note1.p65

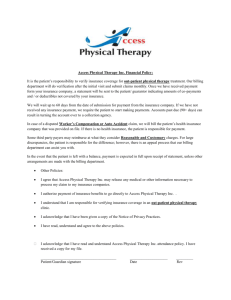

advertisement