The Boston Medical Center Patient Navigation

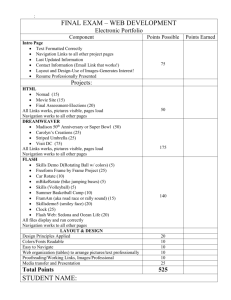

advertisement