Contempt of Court: Criminal Procedure Rule Committee seeks views

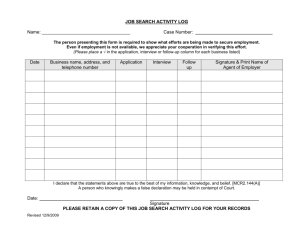

advertisement