guidelines for the management of haemodynamically stable patients

advertisement

ANZ J. Surg. 2007; 77: 614–620

doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2007.04173.x

SPECIAL ARTICLE

GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF HAEMODYNAMICALLY STABLE

PATIENTS WITH STAB WOUNDS TO THE ANTERIOR ABDOMEN

MICHAEL SUGRUE,* ZSOLT BALOGH,† JOAN LYNCH,* JOEL BARDSLEY,‡ GLENN SISSON§

AND JOHN WEIGELT{

*Trauma Department and ‡NSW Ambulance Liaison, Liverpool Hospital, Sydney, Australia, †Department of Trauma,

John Hunter Hospital, Newcastle, Australia, §NSW Institute of Trauma and Injury Management, Sydney, Australia,

and {Division of Trauma/Critical Care, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA

Clinical practice guidelines have been shown to improve the delivery of care. Anterior abdominal stab wounds, although uncommon,

pose a challenge in both rural and urban trauma care. A multidisciplinary working party was established to assist in the development

of evidence-based guidelines to answer three key clinical questions: (i) What is the ideal prehospital management of anterior

abdominal stab wounds? (ii) What is the ideal management of anterior abdominal stab wounds in a rural or urban hospital without

an on-call surgeon? (iii) What is the ideal emergency management of stable patients with anterior abdominal stab wounds when

surgical service is available? A systematic review, using Cochrane method, was undertaken. The data were graded by level of

evidence as outlined by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. Stable patients with anterior abdominal stab

wounds should be transported to the hospital without delay. Any interventions deemed necessary in prehospital care should be

undertaken en route to hospital. In rural hospitals with no on-call surgeon, local wound exploration (LWE) may be undertaken by

a general practitioner if confident in this procedure. Otherwise or in the presence of obvious fascial penetration, such as evisceration,

the patient should be transferred to the nearest main trauma service for further management. In urban hospitals the patient with

omental or bowel evisceration or generalized peritonitis should undergo urgent exploratory laparotomy. Stable patients may be

screened using LWE. Abdominal computed tomography scan and plain radiographs are not indicated. Obese and/or uncooperative

patients require a general anaesthetic for laparoscopy. If there is fascial penetration on LWE or peritoneal penetration on laparoscopy,

then an urgent laparotomy should be undertaken. The developed evidence-based guidelines for stable patients with anterior abdominal stab wounds may help minimize unnecessary diagnostic tests and non-therapeutic laparotomy rates.

Key words: anterior abdominal stab wound, local wound exploration, penetrating trauma, practice guideline.

Abbreviations: ALS, advanced life support; BLS, basic life support; CI, confidence interval; DPL, diagnostic peritoneal

lavage; FAST, focused assessment sonography in trauma; IVP, intravenous pyelogram; LWE, local wound exploration; MAST,

Military Anti-Shock Trousers; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

INTRODUCTION

Historically, there has been a low incidence of stab wound injuries

in Australia and New Zealand.1 The low incidence of stab wounds

has led Australian and New Zealand surgeons to persist with

a more operative approach to their management than in other

countries, particularly in the case of anterior abdominal stab

wounds.1

Missed intra-abdominal injury is associated with significant

morbidity and even mortality.2,3 However, there is also considerable morbidity associated with non-therapeutic laparotomy.1

These guidelines examine evidence to make recommendations

on how to best manage the stable patient with abdominal stab

M. Sugrue MD, FRCSI, FRACS; Z. Balogh MD, FRACS; J. Lynch RN;

J. Bardsley; G. Sisson BN; J. Weigelt MD, FRACS.

Correspondence: Professor Michael Sugrue, Trauma Department, Liverpool Hospital, Locked Bag 7103, Liverpool BC, Sydney, New South Wales

1871, Australia.

Email: michael.sugrue@swsahs.nsw.gov.au

Accepted for publication 31 October 2006.

Ó 2007 Royal Australasian College of Surgeons

wounds and, in effect, reduce missed injury while minimizing

negative laparotomy rates.

It is well recognized that intra-abdominal injuries from penetrating abdominal trauma are difficult to identify by physical

examination alone. Initial physical examination may be unreliable

because of the patient being under the influence of drugs and/or

alcohol.4 In order not to miss injuries, the surgeon must have

a high index of suspicion for their presence. This high index of

suspicion may translate to liberal use of exploratory laparotomy.5

Both therapeutic and non-therapeutic laparotomies are potentially

associated with complications and surgery should be carried

out only when necessary to minimize these.6 In addition,

non-therapeutic laparotomy may result in a hospital length of

stay of up to 5–7 days (compared with 1 day for non-operative

management).7

Determination of the most reliable, safe, efficient and costeffective diagnostic and therapeutic modalities is a key focus of

these clinical practice guidelines. The guidelines will make

evidence-based recommendations for the management of patients

with anterior abdominal stab wounds presenting to both rural and

urban hospitals.

MANAGEMENT OF HAEMODYNAMICALLY STABLE PATIENTS

615

METHODS

RESULTS

The development of the guidelines followed the processes outlined by the Australian National Health and Medical Research

Council.8–10

A multidisciplinary working party was established to assist in

the development of key clinical questions and the construction

of evidence-based guidelines. The following questions where

prepared by the working party: (i) What is the ideal prehospital

management of the patient with an anterior abdominal stab

wound? (ii) What is the ideal management of the stable patient

with anterior abdominal stab wound without an on-call surgeon? (iii) What is the ideal management of the stable patient

with anterior abdominal stab wound when surgical service is

available?

A systematic review, using Cochrane method, was undertaken. MEDLINE, Embase, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Controlled Clinical Trials were searched

for all the available years. Articles were searched by title and

abstracts of relevant articles retrieved for further evaluation.

Full text of articles meeting predefined criteria was retrieved.

The articles were then graded by their level of evidence

described by the Australian National Health and Medical

Research Council (Table 1).10–13 Recommendations were formulated from the most rigorous evidence of acceptable quality.

The guidelines were reviewed by the working party and by key

clinicians from Australia and internationally to ensure their

appropriateness.

For possible inclusion, 698 articles were screened by title.

Articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded

resulting in 120 studies that were further evaluated in terms of

level of evidence. Exclusion of articles that were superseded by

a higher level of evidence resulted in 79 articles for inclusion. The

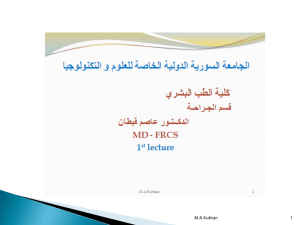

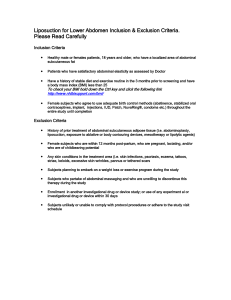

practice guidelines are based on these 79 articles. An algorithm

was drafted from these guidelines and is shown in Figure 1.

DEFINITIONS

The anterior abdomen is anatomically defined as anterior costal

margins to inguinal creases, between the anterior axillary lines.

Management of stab wounds to the thoracic abdomen is not covered by these guidelines. Patients with anterior abdominal stab

wounds who are unstable are not included in these guidelines as

they obviously require immediate surgery.

The haemodynamically stable patient is defined as a patient

with a systolic blood pressure (SBP) >90 mmHg, a heart rate

<120 b.p.m. and without clinical signs of shock.

Table 1. National Health and Medical Research Council levels of

evidence

Level I

Level II

Level III-1

Level III-2

Level III-3

Level IV

Evidence obtained from a systematic review of

all relevant randomized control trials

Evidence obtained from at least one properly

designed randomized control trial

Evidence obtained from well-designed

pseudorandomized controlled trials (alternate

allocation or some other method)

Evidence obtained from comparative studies

(including systematic reviews of such studies)

with concurrent controls and allocation not

randomized, cohort studies, case–control studies

or interrupted time series with a control group

Evidence obtained from comparative studies

with historical control, two or more single-arm

studies or interrupted time series without a

parallel control group

Evidence obtained from a case series, either posttest

or pretest/posttest

Ó 2007 Royal Australasian College of Surgeons

RECOMMENDATIONS

Clinical question

What is the ideal prehospital management of anterior abdominal

stab wounds?

Guideline

Patients with anterior abdominal stab wounds should be rapidly

transported to hospital with minimal scene time. Airway control

using basic life support (BLS) manoeuvres and control of external

haemorrhage is important.14 No other on-scene care should be

provided and transfer should occur as rapidly as possible to hospital. I.v. access should be obtained en route.

Scientific foundation

A meta-analysis undertaken by Sethi concluded that there was

insufficient evidence to determine the efficacy of advanced life

support (ALS) in prehospital trauma care.15 In the absence of such

evidence, Sethi suggests that strong argument could be made that

prehospital (ALS) should not be promoted.

In the absence of a large prospective randomized trial and in

acknowledgement of the difficulties of undertaking such,

Liberman attempted to provide objective evidence on all aspects

of prehospital trauma care through meta-analysis of non-randomized trials. The paper found that ALS increases mortality rate by

2.5 times compared with BLS (adjusted odds ratio 2.59).16

Although combining non-randomized trials has some limitations,

this paper represents the best level of evidence available to date.

Several non-randomized studies have supported Liberman’s

conclusion showing no benefit or worse outcomes in trauma

patients who received ALS in the prehospital setting.17–20 In the

1970s and 1980s, Lewis advised that ALS should not be introduced.21 This was followed by arguments by Trunkey who suggested that there should be little investment in ALS.22

Intubation. The role of intubation in the prehospital setting has

not been fully evaluated. Observational studies have shown mixed

findings. Although Winchell and Hoyt found improved survival

in head-injured patients who underwent prehospital intubation

(64 vs 74% mortality), Winchell and colleagues found advanced

airway management in the field to increase mortality (33 vs

24.2%, P < 0.05).23 The role of pre-hospital intubation is uncertain and requires further investigation.

Intravenous placement and fluid resuscitation. The landmark

study of Bickell et al. has raised serious questions regarding the

administration of i.v. fluid to bleeding trauma patients. In his

prospective study, comparing immediate with delayed fluid resuscitation on 598 patients with penetrating torso injuries with

a blood pressure of 90 or less, he found that patients with delayed

fluid resuscitation had significantly higher survival (30 vs 38%;

616

SUGRUE ET AL.

Fig. 1. Clinical algorithm for

management of anterior abdominal

stab wounds. SBP, systolic blood

pressure.

Anterior abdominal stab wound

Haemodynamically unstable?

(SBP <90mmHg) or evisceration of omentum or bowel or

generalised peritonitis

YES

NO

Thin and cooperative?

YES

Urgent laparotomy

<15min

NO

Local wound exploration

Laparoscopy

Anterior fascial penetration

Peritoneal penetration?

NO

Local wound care +

early discharge

YES

YES

Exploratory laparotomy

NO

Local wound care and early

discharge

relative risk for death with early fluid administration 1.26 (95%

confidence interval (CI) 1.00–1.58)).24 Turner and colleagues replicated this study; however, they failed to find any difference in

outcome because of significant violation in study protocol with

31% of patients in the early fluid group receiving no fluids and

20% of the delayed/no fluid group receiving fluids.

A randomized trial involving patients suffering non-traumatic

gastrointestinal haemorrhage found decreased mortality in those

randomized to delayed fluid resuscitation.25

Dutton et al. evaluated fluid resuscitation aimed at maintaining

an SBP of 100 or 70 mmHg (less than 1000 mL fluid) in a randomized trial. This study found no benefit of maintaining SBP at

100 mmHg compared with 70 mmHg (mortality 7.3% in both

groups, relative risk 1.00 (95%CI 0.26–3.81).26

If, however, the patient appears to be dying, then aggressive

fluid resuscitation may be instigated. Aprahamian et al.

reviewed 112 patients with abdominal vascular injuries and their

prehospital vital signs. He found an SBP of 60 mmHg to be

a critical value. Although 30 of the 43 patients with pressures

greater than 60 mmHg lived (30.2% mortality), only 3 of the 21

with pressures less than 60 mmHg survived (85.7% mortality)

(P < 0.0001). This suggests that i.v. fluid administration may

increase chances of survival in patients with an SBP of

60 mmHg or less.27

Military Anti-Shock Trousers suit. A randomized trial undertaken by Pepe et al. found that the Military Anti-Shock Trousers

(MAST) suit offered no survival advantage in 175 patients with

penetrating abdominal trauma.28 A MAST suit should not therefore be applied under any circumstance as it has been shown to

increase mortality (31 vs 25%, P < 0.05).28,29

Clinical question

What is the ideal management of anterior abdominal stab wounds

in a rural or urban hospital without an on-call surgeon?

Guideline

In a thin patient, local wound exploration (LWE) by the general

practitioner should be undertaken to determine the presence of

anterior rectus sheath (fascial) penetration.2,30,31 A confident diagnosis of no fascial penetration should result in the patient being

sutured loosely, observed for a period of 24 h and discharged the

following day from the rural hospital. This option depends on the

general practitioner’s basic surgical skills and should not be

undertaken unless the doctor is confident in this procedure. Determination of fascial penetration should result in the patients’

immediate transfer to the nearest main trauma service.

Scientific foundation

LWE has been used by many institutions for determining the need

for laparotomy.2,31–35 Criticisms of LWE have stemmed from its

inaccuracy in obese patients or patients with thick abdominal

musculature which makes observation of the peritoneum difficult.

If, however, LWE is used as a screening tool to identify patients

with an intact fascia, then the sensitivity is 100% and specificity is

96%.2 Both Oreskovich and Carrico30 and Goldberger et al.31 have

evaluated the safety and efficacy of LWE.

Oreskovich and Carrico used LWE in the initial assessment of

386 patients with stab wounds to the anterior abdomen. If there

was no evidence of fascial penetration, then patients were discharged from the hospital. Application of this protocol resulted

Ó 2007 Royal Australasian College of Surgeons

MANAGEMENT OF HAEMODYNAMICALLY STABLE PATIENTS

in no missed injuries and <10% negative laparotomy rate.30 Goldberger et al. had similar results in a series of 29 patients undergoing LWE, concluding that LWE is reliable as an initial

diagnostic screening procedure provided adequate observation

is available. In patients where LWE was equivocal (obese or

uncooperative patients), diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) was

used with success.31

Clinical question

What is the ideal emergency management of stable patients with

anterior abdominal stab wounds when surgical service is

available?

Guideline

Haemodynamically stable patients who have generalized peritonitis or evisceration should undergo early exploratory laparotomy.36–39 In a thin and cooperative patient, LWE should be

undertaken to determine the presence of anterior rectus sheet

fascial penetration.2,30,31 Determination of fascial penetration

should result in the patients’ immediate transfer to the operating theatre. If LWE cannot be confidently undertaken

because of obesity, uncooperative patients or poor or inadequate view of the abdominal rectus sheath, the patient may

alternatively undergo laparoscopy or DPL. Given Australian

and New Zealand surgeon’s experience with general laparoscopy, laparoscopy may be the preferred approach. In the event

that either of these examinations is positive or indeterminate,

the patient should be promptly transferred to the operating

theatre.

Scientific foundation

Probabilities. Although the site of penetration may provide

clues as to which organs could be injured, the site of entry alone

does not accurately predict organs at risk.40

The greatest predictor of significant intra-abdominal injury is

haemodynamic instability and abnormal physical examination.

The positive predictive value of shock for predicting positive

laparotomy is well over 80%.2,41 For patients presenting without

signs of shock but with signs of generalized peritonitis the incidence of significant intra-abdominal injury approaches 85%.39,42

In the presence of omental or bowel evisceration serious abdominal injuries may be found in 75% of patients, with half of these

having two or more organ injuries.36,37,42,43

Patients without signs of shock, peritonitis or evisceration are

more difficult to assess. The incidence of intra-abdominal injury

in asymptomatic patients is variably reported between 8 and 28%;

this variation is because of institutional differences in the definition of stable patients.2,32,34,40 The risk of injury increases in the

presence of peritoneal penetration. In all, 68–70% of patients with

peritoneal penetration will have an organ injury,2,31 37% of these

resulting in serious morbidity if left untreated.2

The incidence of occult diaphragmatic injury in asymptomatic

patients with anterior abdominal stab wounds is approximately

7%, which if undetected is associated with high risk of subsequent

hollow viscus herniation.2

The most commonly injured organs are the liver (22%), omentum (18%), mesentery (10%), stomach (8%), diaphragm and

pleura (8%), small bowel (4%), large bowel (3%) and spleen

(3%).44

Ó 2007 Royal Australasian College of Surgeons

617

Investigations. Clinical examination has a reported sensitivity

of 88–100% and specificity of 79–94% for identifying intraabdominal injury requiring surgical management.36,39,41–43,45

Clinical examination assessing for signs of shock, continuing

haemorrhage, evisceration and generalized peritonitis will therefore identify most of the patients (90%) with intra-abdominal

injury requiring laparotomy. However, 1–10% may have a significant injury that will go undetected despite thorough clinical

examination. Physical examination should therefore be supplemented with a more accurate screening test.

LWE has been used by many institutions for determining the

need for laparotomy.2,31–35 When LWE is used as a screening tool

to assess the integrity of the fascia, it is highly accurate and will

not miss any injury (sensitivity 100%, specificity 96%).2 The

success of LWE is dependent on an adequate view of the peritoneum and individual clinician’s skills. If a fascial penetration

cannot be excluded by LWE, DPL or laparoscopy may be undertaken in its place.

The accuracy of DPL has been variable across studies with

a sensitivity of 91–100% and specificity of 86–99% for predicting

a positive laparotomy.46–50 Its use in penetrating trauma has also

been questioned.49,51 Reports on RBC counts used for positive

DPL have varied from 1000 to 100 000/mm3. In an attempt to

minimize false-negative results, both Sriussadaporn et al.46 and

Nagy et al.49 have undertaken prospective studies examining the

sensitivity and specificity of positive DPL, which they defined as

the aspirate of 10 mL of frank blood or RBC count of

10 000 mm3. Application of these criteria in patients with anterior

penetrating abdominal trauma has resulted in a sensitivity and

specificity of 95–100% and 87–99%, respectively.46,49

Patients who have upper abdominal stab wounds are at higher

risk of diaphragmatic injury that will not be detected by DPL.2,46

Therefore, these patients should undergo diagnostic laparoscopy

without DPL to exclude the possibility of diaphragmatic injury.52

Laparoscopy has proven its accuracy in evaluating peritoneal

penetration and diaphragmatic injury.52–55

Screening laparoscopy is highly accurate for excluding haemoperitoneum, upper abdominal organ injuries, diaphragmatic lacerations and retroperitoneal haematomas.53,54,56,57 However,

laparoscopy as a diagnostic tool particularly in detecting injuries

to the lower abdominal organs and hollow viscus is poor (sensitivity 18–50%). Therefore, laparoscopy should be used chiefly to

rule out peritoneal penetration and diagnose diaphragmatic perforation. The sensitivity for the detection of injury to these structures is 98–100%.56,58 Laparoscopy should be carried out with

a 30° telescope to help see the potential site of penetration of

the abdominal wall.

A randomized study undertaken by Leppaniemi evaluated the

use of diagnostic laparoscopy versus exploratory laparotomy in

managing patients with abdominal stab wounds. Leppaniemi did

not recommend use of laparoscopy. Hospital morbidity, length of

hospital stay, cost and postdischarge disability were indifferent

between the two groups. Postoperative pain and cosmetic results

were not assessed in this study. Long-term outcomes such as incisional hernias and adhesive intestinal obstructions remain

unknown.2

Plain radiographs of the abdomen are not useful in patients with

stab wounds to the anterior abdomen unless there is suspicion of

an imbedded foreign body.32,34,59 A study by Kester et al. examining patients with abdominal stab wounds found that an overwhelming majority of patients with injury requiring repair had

a normal abdominal radiograph.59

618

SUGRUE ET AL.

Computed tomography scan of patients with abdominal stab

wounds identifies solid organ injury with great accuracy (100%

sensitivity, 96% specificity) and evaluates the retroperitoneum

well. It does not, however, detect peritoneal penetration and is

reported to be unreliable in detection of bowel and diaphragmatic

injuries.32,60,61 It should not therefore be used for assessment of

patients with anterior abdominal stab wounds.

ASSESSMENT AND DECISION-MAKING

Although most serious injuries will declare themselves on initial

clinical assessment, there is a small but significant group of

patients with normal vital signs and physical examination that

may have an occult injury that if missed can cause serious morbidity. The proposed algorithm encourages the use of screening

tools in line with the risk of injury, which should decrease the

incidence of missed injury and inappropriate diagnostic testing.

This aims to minimize morbidity associated with invasive tests.

Decision-making is based on the result of each screening tool

and location of the stab wound. LWE is the initial procedure of

choice as it does not miss any injuries and is not associated with

morbidity. As the incidence of intra-abdominal injury in patients

with peritoneal penetration exceeds 60%, exploratory laparotomy

is warranted. However, the surgeon should be mindful of diaphragmatic injury in high abdominal stab wounds. Concomitant

injury to the pleura should be evaluated using a chest radiograph

to rule out pneumothorax.

In the past it has been the practice at many trauma centres to

carry out a one-shot intravenous pyelogram (IVP) to evaluate the

contralateral kidney in the event that a nephrectomy was required.

The prevalence of a non-functioning kidney with a normal kidney

on the contralateral side is less than 1%. Unilateral renal agenesis

is even more uncommon with a prevalence of less than 0.1%. Nagy

et al., in their evaluation of 175 patients with penetrating abdominal wounds, found that 1.1% of their patients had an uninjured

kidney that could not be observed using a one-shot IVP.62 The

sensitivity and specificity of one-shot IVP was found by Patel

and Walker to be 25 and 76%, respectively.63 In light of the low

incidence of kidney agenesis or non-functioning kidney, the inaccuracy of one-shot IVP and the delay it imposes to definitive management, there is no justification to undertake one-shot IVP. During

laparotomy renal injury can be identified if present. In the unusual

event that a nephrectomy was required, palpation of the other kidney should occur. To assess function of the kidney when a severe

injury is present and bleeding is controlled, one can inject methylene blue and see if it is excreted. For this, one must have a nonfunctioning injured kidney or occlude the ureter on the injured side.

Morbidity and mortality from missed injury are greater than

those associated with non-therapeutic laparotomy.52 Although this

does not justify exploratory laparotomy for all patients, surgeons

should have a low threshold for surgical exploration if diagnostic

tests are equivocal. Focused assessment sonography in trauma

(FAST) has little role to play in the stable patients. However, if free

fluid is detected, then that would be an indication for surgery. A

negative FAST, however, does not exclude intra-abdominal injury.64

CONCLUSION

Patients should be transported to hospital without delay and procedures, such as i.v. cannulation, carried out en route to hospital.

Selective management of anterior abdominal stab wounds, using

clinical examination, LWE, and/or laparoscopy or DPL, has been

evaluated in multiple institutions and is reported to be safe and

efficacious.30,40,65–68 However, the success of this management

protocol is dependent on individual practitioner skills. In a rural

environment, if DPL or LWE cannot be carried out confidently,

then it is recommended that the patient be transferred to the main

trauma centre for further ancillary diagnostic work-up. Unnecessary investigations, especially abdominal radiographies and

abdominal computed tomography scans, should be avoided. In

the rural hospital determination of either fascial or peritoneal

penetration will decrease unnecessary interhospital transfers and

in urban centres minimize non-therapeutic laparotomies and morbidity from missed injury.

REFERENCES

1. Cameron P, Civil I. The management of anterior abdominal stab

wounds in Australasia. Aust. N. Z. J. Surg. 1998; 68: 510–13.

2. Leppaniemi A, Haapiainen R. Diagnostic laparoscopy in abdominal stab wounds: a prospective, randomized study. J. Trauma

2003; 55: 636–45.

3. Demetriades D, Rabinowitz B. Selective conservative management of penetrating abdominal stab wounds, a prospective study.

Br. J. Surg. 1984; 71: 92–4.

4. Ferrada R, Birolini D. New concepts in the management of

patients with penetrating abdominal wounds. Surg. Clin. North

Am. 1999; 79: 1331–56.

5. Cushing BM, Clark DE, Cobean R, Schenarts PJ, Rutstein LA.

Blunt and penetrating trauma – has anything changed? Surg.

Clin. North Am. 1997; 77: 1321–32.

6. Renz B, Feliciano DV. Unnecessary laparotomies for trauma.

J. Trauma 1995; 38: 350–56.

7. Weigelt JA, Kingman RG. Complications of negative laparotomy

for trauma. Am. J. Surg. 1987; 156: 544–7.

8. Haan J, Kole K, Brunetti A, Kramer M, Scalea T. Nontherapeutic

laparotomies revisted. Am. Surg. 2003; 69: 562–5.

9. National Health and Medical Research Council. A Guide to the

Development, Implementation and Evaluation of Clinical Practice Guidelines. ISBN 1864960485. Canberra: National Health &

Medical Research Council, 1999.

10. National Health and Medical Research Council. How to Use the

Evidence: Assessment and Application of Scientific Evidence.

Canberra: Biotext, 2000.

11. National Health and Medical Research Council. How to Review

the Evidence: Systematic Identification and Review of the Scientific Literature. Canberra: Biotext, 1999.

12. National Health and Medical Research Council. A Guide to the

Development, Implementation and Evaluation of Clinical Practice Guidelines. Canberra: Biotext, 1998.

13. Liddle J, Williamson M, Irwig L. Method for Evaluating

Research Guideline Evidence (MERGE). Sydney: NSW Health

Department, 1996.

14. Stockinger ZT, McSwain NE Jr. Prehospital endotracheal intubation for trauma does not improve survival over bag-valve-mask

ventilation. J Trauma 2004; 56: 531–6.

15. Sethi D, Kwan I, Kelly AM, Roberts I, Bunn F (on behalf of the

WHO Pre-Hospital Trauma Care Steering Committee). Advanced

trauma life support training for ambulance crews. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2001; issue 2, Art. No. CD003109.

DOI: 1002/14651858.CD003109.

16. Liberman M, Mulder D, Sampalis JS. Advanced or basic life

support for trauma: meta-analysis and critical review of the literature. J. Trauma 2000; 49: 584–99.

17. Potter D, Goldstein G, Fung SC, Selig M. A controlled trial of

prehospital advanced life support in trauma. Ann. Emerg. Med.

1988; 17: 582–8.

Ó 2007 Royal Australasian College of Surgeons

MANAGEMENT OF HAEMODYNAMICALLY STABLE PATIENTS

18. Cayten CG, Murphy JG, Stahl WM. Basic life support versus

advanced life support for injured patients with an injury severity

score of 10 or more. J. Trauma 1993; 35: 460–66.

19. Sampalis JS, Lavoie A, Williams JI, Mulder DS, Kalina M. Impact

of on-site care, prehospital time, and level of in-hospital care

on survival in severely injured patients. J. Trauma 1993; 34:

252–61.

20. Liberman M, Mulder D, Lavoie A, Denis R, Sampalis JS. Multicenter Canadian study of prehospital trauma care (Comment).

Ann. Surg. 2003; 237: 153–60.

21. Lewis F. Ineffective therapy and delayed transport. Prehospital

Disaster Med. 1989; 4: 129–30.

22. Trunkey DD. Is ALS necessary for pre-hospital trauma care?

J. Trauma 1984; 24: 86–7.

23. Winchell J, Hoyt D. Endotracheal intubation in the field

improves survival in patients with severe head injury. Arch. Surg.

1994; 12: 413–16.

24. Bickell WH, Wall MJ Jr, Pepe PE, Martin RR, Ginger VF,

Allen MK. Immediate versus delayed fluid resuscitation for

hypotensive patients with penetrating torso injuries. N. Engl. J.

Med. 1994; 331: 1105–9.

25. Blair SD, Janvrin SB, McCollum CN, Greenhalgh RM. Effect of

early blood transfusion on gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Br. J.

Surg. 1986; 73: 783–5.

26. Dutton RP, MacKenzie CF, Scalea TM. Hypotensive resuscitation during active haemorrhage: impact on in-hospital mortality.

J. Trauma 2002; 52: 1141–6.

27. Aprahamian C, Thompson B, Towne J, Darin J. The effect of

a paramedic system on mortality of major open intra-abdominal

vascular trauma. J. Trauma 1983; 23: 687–90.

28. Pepe PE, Bass RR, Mattox KL. Clinical trials of the pneumatic

anti-shock garment in the urban prehospital setting. Ann. Emerg.

Med. 1986; 15: 1407–10.

29. Mattox KL. Prospective MAST study in 911 patients. J. Trauma

1989; 29: 1104–11.

30. Oreskovich MR, Carrico CJ. Stab wounds of the anterior abdomen. Analysis of a management plan using plan using local

wound exploration and quantitative peritoneal lavage. Ann. Surg.

1983; 198: 411–19.

31. Goldberger JH, Bernstein DM, Rodman GH Jr, Suarez CA.

Selection of patients with abdominal stab wounds for laparotomy. J. Trauma 1982; 22: 476–80.

32. Rehm CG, Sherman R, Hinz TW. The role of CT scan in the

evaluation for laparotomy in patients with stab wounds of the

abdomen. J. Trauma 1989; 29: 446–50.

33. Feliciano DV, Bitondo CG, Steed G, Mattox KL, Burch JM,

Jordon GL Jr. Five hundred open taps or lavages in patients

with abdominal stab wounds. Am. J. Surg. 1984; 148: 772–7.

34. Thompson JS, Moore EE, Van Duzer-Moore S, Moore JB,

Galloway AC. The evolution of abdominal stab wound management. J. Trauma 1980; 20: 478–84.

35. Leppaniemi A, Haapianien RK. Selective non-operative management of abdominal stab wounds: a prospective randomized study.

World J. Surg. 1996; 20: 1101–5.

36. Nagy KK, Roberts R, Joseph KT, An GC, Barrett J. Evisceration

after abdominal stab wounds: is laparotomy required? J. Trauma

1999; 47: 622–4.

37. Medina M, Ivatury RR, Stahl WM. Omental evisceration through

an abdominal stab wound: is exploratory laparotomy mandatory?

Can. J. Surg. 1984; 27: 399–401.

38. Burnweit CA, Thal ER. Significance of omental evisceration in

abdominal stab wounds. Am. J. Surg. 1986; 152: 670–73.

39. Leppaniemi AK, Voutilainen PE, Haapiainen RK. Indications for

early mandatory laparotomy in abdominal stab wounds. Br. J.

Surg. 1999; 86: 76–80.

40. McCarthy MC, Lowdermilk G, Canal DF, Broadie TA. Prediction of injury caused by penetrating wounds to the abdomen,

flank, and back. Arch. Surg. 1991; 126: 962–6.

Ó 2007 Royal Australasian College of Surgeons

619

41. Huizinga WK, Baker LW, Mtshali ZW. Selective management of

abdominal and thoracic stab wounds with established peritoneal

penetration: the eviscerated omentum. Am. J. Surg. 1987; 153:

564–8.

42. Robin AP, Andrews JR, Lange DA, Roberts RR, Moskal M,

Barrett JA. Selective management of anterior abdominal stab

wounds. J. Trauma 1989; 29: 1684–9.

43. Zubowski R, Nallathambi M, Ivatury RR, Stahl WM. Selective

conservatism in abdominal stab wounds: efficacy of serial physical examination. J. Trauma 1988; 28: 1665–8.

44. Wilder JR, Kudchadkar A. Stab wounds of the abdomen: observe

of explore?. JAMA 1980; 243: 2503–5.

45. Shorr RM, Gottlieb MM, Webb K, Ishiguro L, Berne TV. Selective management of abdominal stab wounds. Importance of physical examination. Arch. Surg. 1988; 123: 1141–5.

46. Sriussadaporn S, Pak-art R, Pattaratiwanon M, Phadungwidthayakorn A, Wongwiwatseree Y, Labchitkuslol T. Clinical uses

diagnostic peritoneal lavage in stab wounds of the anterior abdomen: a prospective study. Eur. J. Surg. 2002; 168: 490–93.

47. Muckart DJ, McDonald MA. Evaluation of diagnostic peritoneal

lavage in suspected penetrating abdominal stab wounds using

dipstick techniques. Br. J. Surg. 1991; 78: 696–8.

48. Marx JA, Moore EE, Jorden RC, Eule J Jr. Limitations of computed tomography in the evaluation of acute abdominal trauma:

a prospective comparison with diagnostic peritoneal lavage.

J. Trauma 1985; 25: 933–7.

49. Nagy KK, Roberts RR, Joseph KT, Smith RF, An GC, Bokhari F.

Experience with over 2500 diagnostic peritoneal lavages. Injury

2000; 31: 479–82.

50. Duus BR, Hauch O, Damm P, Hoffmann J. Peritoneal lavage for

the evaluation of patients with equivocal signs after abdominal

trauma. Acta Chir. Scand. 1986; 152: 601–4.

51. Muckart DJ, McDonald MA. Unreliability of standard quantitative criteria in diagnostic peritoneal lavage performed for suspected penetrating abdominal stab wounds. Am. J. Surg. 1991;

162: 223–7.

52. Demaria EJ, Dalton JM, Gore DC, Kellum JM, Sugerman HJ.

Complementary roles of laparoscopic abdominal exploration and

diagnostic peritoneal lavage for evaluating abdominal stab

wounds: a prospective study. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech.

A 2000; 10: 131–6.

53. Ortega AE, Tang E, Froes ET, Asensio JA, Katkhouda N,

Demetriades D. Laparoscopic evaluation of penetrating

thoracoabdominal traumatic injuries. Surg. Endosc. 1996; 10:

19–22.

54. Villavicencio R, Aucar J. Analysis of laparoscopy in trauma.

J. Am. Coll. Surg. 1999; 189: 11–20.

55. Ivatury RR, Simon RJ, Weksler B et al. Laparoscopy in the

evaluation of the intrathoracic abdomen after penetrating injury.

J. Trauma 1992; 33: 101–9.

56. Ertekin C, Onaran Y, Guloglu R, Gunay K, Taviloglu K. The use

of laparoscopy as a primary diagnostic and therapeutic method in

penetrating wounds of the lower thoracal region. Surg. Laparosc.

Endosc. Percutan. Tech. 1998; 8: 26–9.

57. Ivatury RR, Simon RJ, Stahl WM. A critical evaluation of laparoscopy in penetrating abdominal trauma. J. Trauma 1993; 34:

822–7.

58. Fernando HC, Alle KM, Chen J, Davis I, Klein SR. Triage by

laparoscopy in patients with penetrating abdominal trauma. Br. J.

Surg. 1994; 81: 384–5.

59. Kester DE, Andrassy RJ, Aust JB. The value and costeffectiveness of abdominal roentgenograms in the evaluation of

stab wounds to the abdomen. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1986; 162:

337–9.

60. Soto JA, Morales C, Munera F, Sanabrina A, Guevara JM,

Suarez T. Penetrating stab wounds to the abdomen: the use of

serial US and contrast-enhanced CT in stable patients. Radiology

2001; 220: 365–71.

620

61. Shanmuganathan K, Mirvis SE, Chiu WC, Killeeen KL,

Scalea TM. Triple-contrast helical CT in penetrating torso trauma:

a prospective study to determine peritoneal violation and the need

for laparotomy. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2001; 177: 1247–56.

62. Nagy KK, Brenneman FD, Krosner SM et al. Routine preoperative ‘‘one-shot’’ intravenous pyelography is not indicated in all

patients with penetrating abdominal trauma. J. Am. Coll. Surg.

1997; 185: 530–33.

63. Patel VG, Walker ML. The role of ‘‘one-shot’’ intravenous pyelogram in evaluation of penetrating abdominal trauma. Am. Surg.

1997; 63: 350–53.

64. Ollerton JE, Sugrue M, Balogh Z, D’Amours SK, Giles A,

Wyllie P. Prospective study to evaluate the influence of

SUGRUE ET AL.

65.

66.

67.

68.

FAST on trauma patient management. J. Trauma 2006; 60:

785–91.

Taviloglu K. When to operate on abdominal stab wounds. Scand.

J. Surg. 2002; 91: 58–61.

Taviloglu K, Gunay K, Ertrkin C, Calis A, Turel O. Abdominal

stab wounds: the role of selective management. Eur. J. Surg.

1998; 164: 17–21.

van Haarst EP, van Bezooijen BP, Coene PP, Luitse JS. The

efficacy of serial physical examination in penetrating abdominal

trauma. Injury 1999; 30: 599–604.

Gonzalez RP, Turk B, Falimirski ME, Holevar MR. Abdominal

stab wounds: diagnostic peritoneal lavage criteria for emergency

room discharge. J. Trauma 2001; 51: 939–43.

Ó 2007 Royal Australasian College of Surgeons