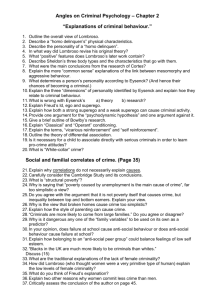

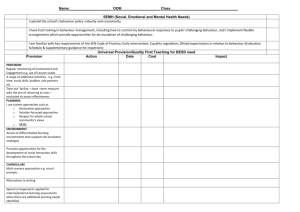

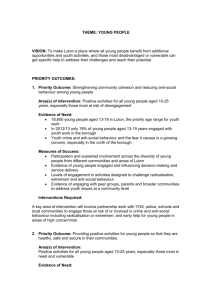

Preventing Children's Involvement in Crime and Anti

advertisement