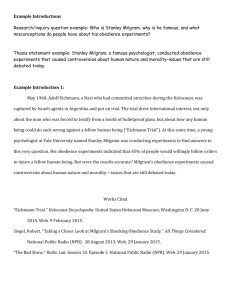

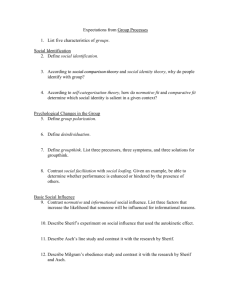

Stanley Milgram's Obedience to Authority

advertisement