Countries engaged in socio-political crises

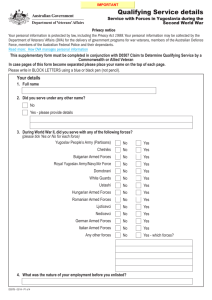

advertisement