Notes on Relativistic Dynamics

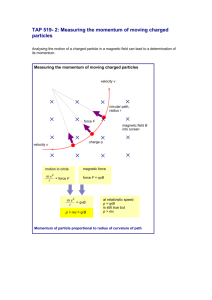

advertisement