PDF - Research Repository

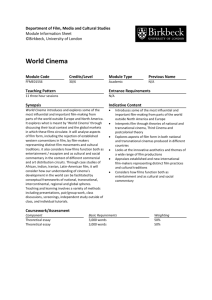

advertisement