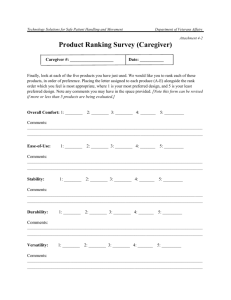

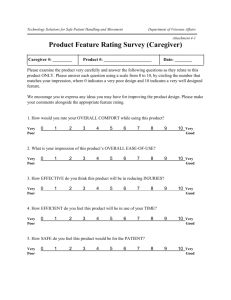

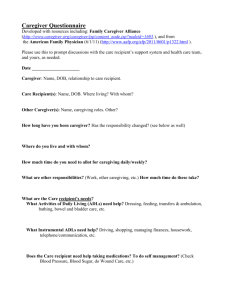

Selected Caregiver Assessment Measures: A Resource Inventory for

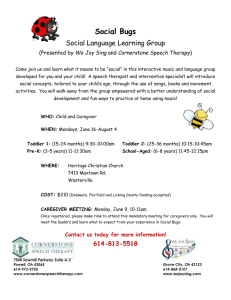

advertisement