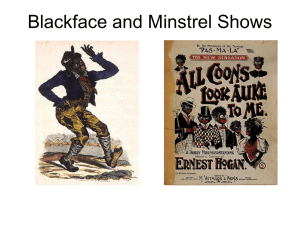

Love and Theft: The Racial Unconscious of Blackface Minstrelsy

advertisement