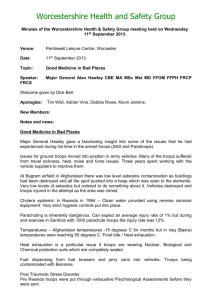

When Our Troops

Come Home

For friends and family who want to

understand and reconnect with

their loved ones.

Ken Jones PhD

When Our Troops Come Home

When Our Troops

Come Home

Ken Jones, PhD

When Our Troops Come Home

Copyright 2008

Ken Jones, PhD

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Cover Design by

Francine Dufour

www.artbyfrancine.com

When Our Troops Come Home

For my brothers

Ned Neathery

Jim Bondsteel

and

Gabe Rollison

When Our Troops Come Home

TABLE OF CONTENTS

For

ward

face to the Original Edition

PART I

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

PART II

Pre

4

The Cauldron

8

15

17

The Iceman

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

21

26

28

Chapter 7

33

Chapter 8

PART III The Journey

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

34

37

41

PART IV The Medusa

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

43

46

48

50

52

55

PART V The Morass

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

59

61

63

65

73

79

PART VI The Metanoia

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

88

91

93

PART VII The Reflection

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

97

99

When Our Troops Come Home

Chapter 30

105

Credits for Chapter Quotes

113

When Our Troops Come Home

Forward

You are not alone. You, the families and friends who await their return –

you, who have experienced combat and know that your world is forever

changed. You are not alone.

Across the decades and generations we, who did our trigger time in Vietnam,

look to you with pride and admiration for who you are – America’s warriors

- the one percent who serve.

We understand the fear and rage and guilt you experience, the nights without

sleep and the need for the next adrenalin fix. We understand the bond, the

love that exists among warriors. We understand how, at first, there are no

words to express the losses you have endured, or the guilt of having

survived.

Understanding these things we who served in Vietnam have an obligation. It

is simply this: That never again shall a generation of America’s warriors

have to endure what we endured on the long journey home.

This then is a beginning, just one of thousands across our country.

When Our Troops Come Home is a description of an interior journey for

warriors returning from combat. It is offered as a gift to families and friends

who desperately want to understand. And it is offered to our warriors as one

more voice reminding you that you are not alone.

Ken Jones

Anchorage, Alaska

May 26, 2008

Memorial Day

www.whenourtroopscomehome.com

When Our Troops Come Home

Preface to the Original Edition

Even now I recall them; space enfolding itself in majesty, the infinite blue of the

clear winter sky extending beyond forever; the immaculate miles of white on white; the

ridgelines and mountaintops articulating the solitude of being - the Brooks Range. March

1968.

I had stood hours before, staring blankly into the humidity and heat, beside the

runway of the Tan Son Nhut Airbase in the Republic of Viet Nam. I still recall the

helplessness and terror of sitting in the window seat, three rows behind the trailing edge

of the 707's right wing, as it taxied onto the active runway and surged toward its takeoff

speed. For most of the month prior to my departure we had been in the Iron Triangle

with the 101st Airborne, trying to stop the 122mm rockets that were raining in on the

airbase during the 1968 Tet Offensive.

I knew that there was no such thing as being short so long as I was within range

of anything in Viet Nam. It was the knowing that turned my knuckles white as I gripped

the armrests and watched the world accelerate along the tarmac outside the aircraft

window.

The last time I was blown up was eight days before I was supposed to leave the

country. There was no such thing as short. So I watched and ate the fear and willed the

aircraft into the sky.

As the jet climbed and turned outward bound, the old staff sergeant sitting next to

me leaned over and offered his reassurance. "Relax son, you're going home." My aching

hands let go of the armrests. I nodded and tried to smile. But even then I knew, there

was no longer any such place as home.

As I watched the unfolding beauty of the Alaska winter I felt like a hundred-yearold child seeing snow for the first time. The aircraft made a sweeping right turn and

headed south. I slept. Finally, we were out of range.

The PA system awakened me. Not the words, but the click of the microphone

button just before the flight attendant's announcement. We were beginning our descent

into Anchorage, Alaska. This was a refueling stop. We could deplane for an hour or so

if we liked. Moments after the stewardess' announcement, a male voice came over the

system in an authentic impersonation of the impersonal monotone flight attendants use

for landing announcements. It was one of the grunts who had been seated up forward.

"Gentlemen, in preparation for our arrival in Anchorage, please bring your tray

tables, seat backs and stewardesses to their full upright position for landing."

The resulting cheers and laughter started exhausted men moving again.

When Our Troops Come Home

When the aircraft stopped, a stairway was pushed up to the front door. The doors

were opened and it took only seconds for the cold to sweep through the cabin. All of us

wore short sleeve, khaki summer uniforms. Deplaning was swift and stumbling.

Brilliant sunshine. How could there be this much sunlight and such intense cold? Inside

the terminal I stood shivering. Even here it was only seventy degrees. How could people

live in these temperatures?

I saw her walking toward me. She was old. Forty, maybe forty-five. She smiled

at me. She walked up and offered me a blue, half-sized, airline-issued blanket.

I gratefully accepted. I remember her. The blanket stopped my shivering and her smile

made me warm. She turned and disappeared into the milling crowd. I didn't get a chance

to thank her. It was one of the kindest things anyone has ever done for me.

When Our Troops Come Home is the continuation of the journey begun in the

frigid sunshine of Anchorage in March of 1968. The journey took sixteen years. This

book is about trauma, specifically, the trauma induced by combat. It is a story recounted

in metaphor and symbol and direct experience. This is the nature of interior journeys.

Such material is intended to be read twice, once with the mind and once with the heart.

During the past three and a half years I have had the opportunity to spend

moments and hours and days and months with human beings who have experienced

trauma. It has been my honor and privilege to share in these people's anguish and

healing. Much of it as a result of my time spent as a volunteer counselor at the

Anchorage Viet Nam Veterans Outreach Center. Many of the men and women I have

spent time with were survivors of combat in Viet Nam. There were also a number of

wives of Viet Nam survivors who were desperately seeking answers to questions they did

not understand; questions about the pain and silence of their husbands concerning

anything to do with Viet Nam.

Trauma, whatever its form, is devastating. It tears the mind, shatters the soul and

breaks the heart. Trauma leaves a human being cut off and isolated. If the pain is not

shared and dissipated, it becomes impacted.

Over and over again I heard the words that "had never been spoken".

The assumption, expressed by the person with whom I talked, was that they were alone in

their anguish. They felt relief when someone spoke their language. It was the same with

me when I began my journey.

It is my hope that, as we spend time together, you will come to understand that,

although this story is recounted around the trauma of combat, it is the possibility of

healing from trauma that is paramount. The nature of trauma is to force people to face

meaninglessness directly. The symbols of a person's life are obliterated. People are left

alone with only themselves. In the desolation and aloneness, through the love of those

willing to share their pain, the mystery of life is renewed and affirmed.

When Our Troops Come Home

Lest anyone be misled, let me say that I am not a psychiatrist or psychologist or a

social worker. I am a grunt. I was trained in recon. I just say what I see.

Truly, there is a place called home. To the lady who met me at the Anchorage

Airport so many years ago - thank you.

Ken Jones

June 1987

Eagle River, Alaska

When Our Troops Come Home

PART I

THE CAULDRON

When Our Troops Come Home

Chapter 1

"First up in the morning, as usual - old men have

guilty dreams - I start the fire and build the coffee.

Our culture runs on coffee and gasoline, the first

often tasting like the second."

Edward Abbey

Down The River

August, 1967. Southwest of Chu Lai. Our cav platoon is linked up with a

company of South Koreans. ROK Marines. The area we're going into is seven miles

wide, twenty-three miles long. It has been declared a free fire zone. It is a VC staging

area. The locals are VC supporters. Our mission is to burn or destroy every structure

and kill anything that moves. People. Animals. Livestock. Anything. Everything.

Search and destroy.

The company of ROK’s has four U.S. Marine advisors, a captain, a sergeant and

two enlisted men. I'm driving the lead track, three zero. It's my job. I've already been

blown up once. I know what this is about.

Hot. It's only mid-morning and the sun beating down on our tracks makes the

metal so hot that our gunners have to sit on their flack jackets. Nobody wants to stand

inside the track when it's moving. We all know the mines are out there.

Nothing. Moving. Waiting. Moving. Nothing. An embankment ahead.

A stream. Banks too high and steep to negotiate. Dense brush beyond.

"Three zero, three six. Find us a place to ford."

"Three zero, roger."

"Hang a left, Ken."

"Roger."

We move out. The rest of the tracks herring-bone. Tracks in column, alternating

their front slopes left and right to establish clear fields of fire. Our track moves on,

paralleling the stream. The feeling settles in. Intercom.

"Jerry?"

"Yeah."

When Our Troops Come Home

"This sucks."

"Yeah."

We move on. The stream turns south. A slight rise to our right front. A steep

drop, maybe fifteen feet down. Sand at the bottom. Fifty meters across. A negotiable

slope on the opposite side. No other place to pass. Stream bank where we came from.

Drainage ditch ahead of us.

"Jerry."

"Yeah."

"This really sucks."

"Yeah."

"Three six. Three zero."

"Roger. Go."

"We got a place to ford."

"Roger. We're moving up."

"Three seven, three six. Move up and cover three zero."

"Three elements, three six. Move east and come on line. Cover."

The tracks move out behind us. We wait. I climb out of my coffin and watch the

tracks move toward us. The ROK's are moving in a crouch. Bayonets fixed. They don't

like it either. The Marine captain is riding three six. The sergeant and one of the enlisted

men are on three seven.

Jim Fleshhood is driving three seven. Jim is my best friend. He's been blown up,

too. We both know.

Jerry is a twenty-seven-year old staff sergeant, my track commander. His eyes

haven't stopped searching the ravine and brush beyond. Our gunners are behind their gun

shields. Ready. Jesus, it's hot.

The tracks and infantry are almost to us. Three seven moves to our left rear.

Clear field of fire. Three two moves to our right rear. Same thing.

When Our Troops Come Home

I look at Fleshhood, the top of his head and his eyes visible above the driver's

hatch. We just look at each other.

"Jerry?"

"Yeah."

"There's a mine in there."

"I know. You see anything?"

"No, but I know it's there."

"Yeah."

The rest of the tracks are set.

"Three zero, three six."

"Three zero."

"The ROK's are sending squads through to secure the other side. Cover."

"Three zero. Roger."

The ROK's move out. Low. Quick. Nothing. Across the sand. Up the opposite

bank. Nothing. We wait. Nothing.

The crack of the radio startles me.

"Three zero. Three six."

"Three zero."

"Let's go."

"Three six, three zero. There's got to be a mine in there. Do you want to sweep it

or walk it first?"

"This is three six. Do you see anything?"

"Three zero. Negative. But it's there."

"Three six, roger. Move out. Slowly."

Jerry and I look at each other. We were blown up together last month. We know.

When Our Troops Come Home

"Well, Ken, you heard the man."

"Yeah, shit." Into the coffin.

"Three two, three six."

"Three two."

"Three two, follow three zero. Stay right in his tracks."

"Three seven, three six."

"Three seven."

"Three seven, hold what you got until three zero makes the far bank then follow

three two across."

"Three seven, roger."

I hold the steering levers and depress the accelerator with my right foot. The

track moves toward the rise. Up the incline. Up. Up. Nursing the levers. Waiting for

the track to counter balance and drop down the opposite side. I hold my breath. Waiting

for the explosion. The track falls forward. Forever. Crunch. We're on the down side of

the slope. Nothing.

I hit the accelerator. Sand flies. Up the other side. Shit. We made it. I explode

out of the driver's compartment. We made it. Jerry and I smile at each other. Three two

is hauling ass across the sand. Right in our tracks. Jesus, we're alive!

Three seven is approaching the berm. ROK infantry coming down on both sides.

Three seven is coming in at a slight angle. Jim's a good driver. Let one side of the track

land before the other and it helps absorb the shock. Front slope in the air. Starting down.

They're going to come down slightly to the right of my tracks. Slightly to the right.

Maybe a quarter of a track width. Ten inches maybe.

The blast knocks me backwards. My legs catch the rim of the driver's hatch.

I pull myself back. Three seven is invisible in the black smoke. ROK's are down and

screaming on both sides of the track. Some just disappeared.

"Six, three six. Dust off! Dust off!"

I rip my headset off. I don't remember running across the sand. The nightmare

begins.

When Our Troops Come Home

Three seven is on its back. Top hatches against the embankment. The rear door

is lodged in the sand at the bottom of the ravine. No way to get inside. Black smoke

billows up from underneath. I can hear the fire without seeing any flames. ROKs are

moving their wounded away. The fuel tanks are going to go. I can hear Fleshhood. He's

inside.

"Get me out. Please! Get me out!"

"Jim!"

"Please get me out. I'm burning!"

There's no way. There's only six inches between the embankment and the driver's

hatch. The barbed wire that was coiled on the front of the track is tangled around

everything.

Panic! Dig at the sand. Someone else is with me. Maybe two others.

Digging…Digging…Crunch. The metal coffin moves. Three five has pulled to the top

of the berm and is trying to bulldoze three seven up. Thirteen tons of metal stuck on its

back. Crunch. Some clearance.

Jim is screaming. The smoke is choking us. The snap of machine gun rounds

beginning to cook off from the heat inside three seven.

"Try the other side!"

Can't see. I fall down the slope. Choking. Tears streaming. Crunch.

Three seven shudders. Around the back. Clearer on this side. A slight breeze.

Snap…snap…snap…snap. I hear the rounds ricocheting inside the track.

He's just laying there. The Marine sergeant. Forehead resting on his arm. No

one else around. Just me and the Marine. He looks up. The eyes. Quiet. Very calm.

"I'm stuck."

"What?"

Crunch.

"Oh, Jesus, I'll be good. Please get me out!" Fleshhood pleading. Others

shouting. Three five's engine roaring. Crunch. I can see daylight under the front of the

track. Hear the scuffling and yelling from the other side.

"Jim! Grab my hand!" someone yells. They're getting to him. Jim screams as

they pull him out through the tangled barbed wire.

When Our Troops Come Home

The Marine. "I'm stuck."

"What's stuck?"

"My leg."

I bend down to look. See the flames inside. Snap…Snap…Snap. Two bodies

already burned black. The gun shield is across his left leg at mid-calf. Right leg clear

but jungle boot and fatigues already smoking.

"Gimme a fucking' fire extinguisher! I need a knife!"

The fire extinguisher appears in my hand. Crunch. Others around. The Marine

and I are alone. Nozzle pointed at his free leg. Swoosh. A white cloud. The

extinguisher freezing in my hand.

"Hit it again!" Crunch.

The gun shield doesn't move. The Marine groans. Head on his forearm. More

fire, reaching us now. Crunch. His fatigues ignite. Crunch. Pull.

"Pull, goddamn it!"

"I can't move."

The smell of flesh burning. The extinguisher is empty. "Where's that fuckin'

knife!" Snap. Snap. Crunch.

"Wait." His hand reaches for my left arm.

"I'll get you out. Just a second."

"No. Wait."

The knife appears. I start to crawl in. The Marine and I are on our bellies. Face

to face. He's on the inside. I'm on the outside. Shit, it's hot. I start to move. He grabs

my flack jacket.

"Wait."

"Bullshit. I gotta get you out."

Quiet eyes look at me.

Snap. Snapsnapsnap.

When Our Troops Come Home

"Shoot me."

"What?"

"Shoot me."

"I can't."

"Please. Just shoot me."

"I can't."

"Please!" Teeth gritted. Eyes quiet.

Time stops. Just the Marine and me.

"Please?"

Snap. Snap.

"Shit."

The M-16 is in my hand. Charging handle back, a round ejects, the bolt springs

forward. Another round chambers. Safety clicks off. On one knee beside the Marine.

Holding his hand. Muzzle to his head. Quiet eyes. Finger on the trigger. Snap. Snap.

Snap. My mind shrieking. Trigger moving back. Quiet, quiet eyes….

Wake up! Sweating. Bile in my mouth. I cannot remember if my weapon ever

fired. I walked away from three seven. I have not yet walked away from the dream.

When Our Troops Come Home

Chapter 2

"I've had all that I wanted of a lot of things I've had.

And a lot more than I wanted of some things that

turned out bad."

Merle Haggard

Wanted Man

Death did not come peacefully in Viet Nam. It did not lie on satin covers,

surrounded by flowers and grieving loved ones. Death was not attended to by skilled

professionals competent in the art of giving death a peaceful appearance. In Viet Nam

death raged, full blown and evil, from the bowels of the earth.

Death shrieked in ecstasy amidst the screams of the wounded. Death glided

effortlessly through the gunfire, pausing only briefly to assure itself that the mutilated

body that another young man held in his arms had no pulse. Death viewed its handiwork

with satisfaction as the scorched, tree-like husk of an incinerated human being was

stuffed, amid retching and curses, into an olive drab plastic bag.

Ever present, death clung defiantly and in jubilation to the absurdity of Viet Nam.

Death exerted its dominance through all of the human senses, especially the most primal

sense, the survivor’s sense of smell. What did Viet Nam smell like? Diesel fuel, cordite,

and death. Survivors did not come back to the world with maturity. They returned very,

very old.

Viet Nam is like herpes. Once you get it, it never really goes away. I went to

Viet Nam when I was 19. I spent 15 years watching, listening, and trying to understand.

I have been a detached observer - being most comfortable in my aloneness.

Our time here will be spent in a sharing of the personal side, the feeling side, of

an experience that, for those of us who were there, is an ever-present reality. My body

was transported back from Viet Nam to Oakland, California in 1968. It took me years to

realize that I died in Viet Nam.

In Viet Nam men were not killed in battle. They died in firefights.

Firefight - an interesting euphemism. Like a rumble after a high school football game.

The theory seemed to be that if the language of war could be made less specific, the act

could be made more palatable. Somehow things were never called by names that

conveyed meaning to anyone who was not a participant.

When Our Troops Come Home

Even name became nomenclature. The killed, maimed and missing became KIA,

WIA, MIA. The language of high-tech war. Detached, dehumanizing, unmeaning words.

In an emerging, high-tech America, Viet Nam refocused our attention on the personal

component of war. The purpose in Viet Nam was never to win. The purpose was to kill.

High-tech death is sudden. Without dignity. Body bags are the epitome of high-tech

death. Mass produced, non-descript, sanitary. While reading Elizabeth Kubler-Ross'

book, On Death and Dying, I was most struck by the length of time in which the patients

had to die.

There were few details given on how men died. The high-tech funeral in Viet

Nam was a memorial service. The difference between a memorial service and a funeral

is that at a memorial service it's easier to forget why you are there. Total acceptance can

be used as effectively as total denial to isolate the living from the dead.

Memorial services never had bodies. We arrived alone. We survived alone.

We went home alone. We survive alone. The most poignant lesson being that survival

does not guarantee anything. Especially continued survival.

I knew a platoon sergeant that came to Viet Nam with the expressly stated

purpose of either winning the Congressional Medal of Honor or being killed. I watched

him get blown to pieces when he stepped on an antitank mine. The rest of us were

relieved that we wouldn't have to be there when he won the medal. And we cried for

him.

So far we have seen Viet Nam as a painting. A flat surface where the artist uses

perspective to evoke feeling and emotion. Viet Nam is not a painting. Viet Nam is a

play. One in which we still participate. A friend of mine once said that God was a

comedian playing to an audience who was afraid to laugh. Perhaps it is time for us to

perform the closing act. To allow the emotion, the feeling, the hurt, the vanity, the

humor, and the tragedy to come to fruition.

For me, the anthem of Viet Nam is Richard Harris singing MacArthur Park.

To this day I do not understand the words. And it makes no difference. The music

touches me. The music is America in motion. Going nowhere. On and On. The

cauldron of Viet Nam. Viet Nam survivors cling to their reality. There is nothing in fast

food America that offers a comparable level of intensity.

When Our Troops Come Home

Chapter 3

"I saw the pain in their faces over and over again.

Most of them haven't cried yet. The fear

of not being able to stop crying is still too great."

Mark Baker

Nam

Survival is the most intense, internalized, selfish, self-sustaining feeling I know.

It is a feeling, once learned, that affects every action. Survival is so primitive in its

origin, so all-consuming in its intensity, that it colors my perception like indelible ink.

For those who learned survival in Viet Nam it is a laundry mark on our soul.

The survivor lives with the guilt and pride, the anger and love, the fear and

exhilaration every day. For those of us who were there, perhaps this is a hand in the

darkness. A knowing that there is at least one other person who understands. One other

person who knows. One other person who cares and says so. And, if there is one,

perhaps there are others. To live with Viet Nam, is like watching your five year old

daughter die of leukemia. More importantly, to realize that to step beyond survival is a

reaffirmation of life.

Viet Nam was a land of rolling hills, plains, high mountains and marshes.

When the monsoons came the rain conformed to the contours of the land. Emotions,

intentions, dreams, and beliefs are the natural contours of the survivor's mind. The

storms encountered in Viet Nam both fit and changed a survivor's mental landscape.

Like the monsoons sweeping over the countryside. Remembering is different than

reliving. Veterans remember. Survivors relive.

The difficulty in integrating survivors back into American society is a shared

responsibility. From a reality of concern, intense camaraderie, and shared moments

amplified by ever present danger, the survivor returned to a world largely devoid of

close, mutual emotional involvement. The "me generation" of an emotionally

protectionist, individualized America.

There is a stereotype of the Viet Nam survivors as antisocial, psychopathic,

aimless, drifting, trained killers. Men enraged, possessed, capable of unspeakable

violence. For years movies, television, books and magazines seemed transfixed by this

image. In a sense it's true. In the same sense that would permit an action thriller to be

made about epileptics.

The survivor is, by Darwinian definition, a killer. Just as there is no crime

without a victim, there is no survivor without the situation to be survived. Perhaps our

first step toward peace is the recognition of our willingness to kill.

When Our Troops Come Home

The survivor knows that he is, in fact, a killer. He has killed before. In the

appropriate situation he would kill again. If war is the outward manifestation of our

belief in competition, perhaps the recognition of cooperation is the basis for peace.

Bullshit!

Why is it that rape is more anxiety provoking than murder? Perhaps because the

victim remains alive to relive the experience. Survivors are victims of psychological and

emotional rape. Asking a survivor what it felt like to kill is like asking a rape victim,

"How was it?" Rape victims and combat survivors can learn a lot from each other.

The artist who specialized in survival used vibrant colors. Red, orange, yellow,

intense shades of green. It is difficult to learn to use pastels and create a comparable

sense of aliveness. Viet Nam was not living. Viet Nam was aliveness. An awareness of

the moment in the sensuous presence of the moment. The survivor now finds few events

that allow the celebration of life in its most intense sense. An awareness of life based on

the personal awareness of death. Real, immediate, felt, understood death. Edward

Abbey makes the comment in passing about the survivors of Korea having a "40 mile

stare". In Viet Nam it was the same look described as a "1,000 yard stare". Everything

seemed to be compressed and distorted.

Viet Nam provided the drama in which men and women experienced themselves

in the extreme. Survivors returned with intensified personalities. They returned as who

they were magnified a thousand times.

Photographs, even film and videotape, do not convey the awareness of combat.

The survivor has encountered the reality of direct experience. Returning to a world of

second-hand information and active uninvolvement is disorienting. Returning from a

world of continuous present to one of assumed tomorrows is unnerving.

The survivor, like a top that has lost its angular momentum, wobbles. The ability

to regain momentum, to stabilize, no longer depends on the circumstances of the

environment. It depends on the survivor's personal capacity to redirect his own energy.

Love was one of the most intense emotions experienced by survivors in Viet

Nam. It was seldom perceived as that. Love was materialized most frequently as its

antithesis; horror, rage, slaughter, and destruction.

Love exists beyond the illusion of its sexual expression. Love is loyalty. Love is

commitment. In the techno-macho illusion of Viet Nam the science of counter guerilla

operations did not acknowledge the emotional basis of high-technology war.

The drug problem in Viet Nam was not heroin. It was adrenaline. Drugs offer an

altered state of consciousness, a different awareness. A perception of reality that is

altogether real for the user. Survival is an altered state of consciousness. The concept of

time is distorted. There were only two times a survivor in Viet Nam was aware of. The

When Our Troops Come Home

date he was due to leave country and the present. The right here, right now. Everything

else was illusion. It was "other time".

Survivors played with "other time" like children reading the National

Geographic. Far away places, beautiful photographs. Discovering the past. Speculating

about the future. But when the word came to saddle up, "other time" was folded and put

away. "Other time" is part of the unresolved question for survivors.

In Viet Nam "other time" was used to construct fantasies. Fantasies about home.

Fantasies about places and people and about how time would be spent. The fantasies

constructed around people were the most intense. Fantasies about important people;

wives, girlfriends, parents, children, friends. People who had cared. People who would

care again.

The fantasies grew. They grew because in a reality of death, hurt, and gut

grinding fear, what a survivor wanted most was love.

The need for love was so great, so intense, so heightened by his Viet Nam

relationships that the fantasies the survivor created were beyond what any of those

important people could comprehend. Survivors seldom asked for love. They expected it.

In the reality of Viet Nam they had experienced love in an altered state. In that altered

state they had created the structure and fabric and intensity of a love that they could not

communicate. A love so powerful that it literally denied death.

The people the survivor came home to, the important people, simply did not

understand what was expected, what was utterly, totally needed from them. And the

survivor had forgotten how to ask.

Once home, the "other time" fantasies created so carefully for so long crumbled.

So, for the survivor who found himself suddenly in a world of uncaring people, Viet Nam

became his "other time". The survivor retreated within himself to the aloneness with

which he was most comfortable. Alone. Like dying of a heart attack during the

Christmas rush at O'Hare International.

As a survivor I felt the exhilaration of personal invincibility. The taste of

seeming immortality. What could I face in the real world that was more demanding than

what I had experienced in combat?

Viet Nam was here. Now. The most perplexing quality of home was that there

was always a tomorrow. How does an adrenaline addict satisfy the need to live in an

altered state, perched on the edge of annihilation, in a world where tomorrow is assumed?

The survivor lives in a world alone. For alone is where the fix is sought.

Where the rush is felt. The survivor was not taught to win, to expect, to savor victory.

The survivor learned to survive. It is the survival ethic that served so well and now

haunts the survivor.

When Our Troops Come Home

The survivor seeks the physical and emotional high of an altered state. When the

current environment does not provide the high directly, the survivor manufactures his

own. The pursuit of survival for the sake of survival. Not to win. Not to grow. Not to

achieve. The survivor does battle within himself to maintain his identity as a survivor.

The survivor was stripped of every shred of America's cultural facade. In a single

moment he stepped through the portal into the infinite emptiness of beyond. He saw the

human condition directly. In the seeing his mind was torn. His soul was shattered.

The fear of winning is real for a survivor. Winning implies completion.

A finishing. A void. An emotional vacuum. What fills the emotional chasm if a survivor

wins? What in the present reality of America provides the impetus, the stimulation, the

high? If I am not a grunt, who am I?

A survivor quoted in Mark Baker's book, Nam, has a similar perception:

"Civilian level is bullshit… you get in a fire fight and you see exactly who's who. There

wasn't anything phony. It was all very real, the realest thing I've ever done. Everything

since seems totally superfluous. It's horseshit". For the survivor, survival is living.

Everything else is just waiting.

When Our Troops Come Home

Chapter 4

"You admitted to error! The trouble with you,

Jakob, is that you have no convictions. Maybe you

didn't make an error, but a discovery. No wonder

you've had so little success."

Russell McCormack

Night Thoughts of a

Classical Physicist

Viet Nam was not the loss of the American vision. It was the beginning of the

transition in which we now find ourselves.

The Zen tradition of Japan has, for centuries, used a riddle called a koan to draw

its students to their own realization. Among the more commonly known koans is one

that states:

You know the sound of two hands clapping. What is the sound of one hand clapping?

The answer to the riddle cannot be deduced from rational, logical thought

processes. If the student is to progress, it is the result of a comprehension, a realization, a

knowing of the answer. An awareness completely outside reason. A perception arrived

at by unasking the question. I sometimes wonder if Viet Nam was not posed as the

ultimate American koan.

Was Viet Nam right or wrong? The question has been continually restated since

the mid-sixties. Could it be that the answer is beyond the context of the question?

Perhaps the problem is that the question has not yet been unasked in a form that will

provide us with comprehension.

Viet Nam produced a generation of trained skeptics. Those who know that

appearances are not reality. The knowing that a peaceful appearance is a prelude to

violence. From a world of knowing to a world where even the questions have not been

clearly stated. It's too bad that Jane Fonda and Green Peace cannot devote as much

energy to saving survivors as they commit to saving whales. Jane, where were you when

we needed you?

Viet Nam was not a random, murderous chaos played out across the landscape of

time, space and the American consciousness. It was a carefully orchestrated, shared

experience of a generation.

Viet Nam was a shared experience for all America. An experience that polarized

our people. An event that created both the combatants and the protesters. Viet Nam

brought back intense emotions to an unfeeling technological culture. America continues

to relive Viet Nam. If it is true that a life of moderation is best achieved by living some

When Our Troops Come Home

time in extremes, then perhaps we are moving toward moderation. We have intensely

experienced war and the protest against it.

In a world perceived in the clinical terms of science and technology, emotions

inhibit progress. While humanity may deal in feelings, governments are formulated and

maintained by the strength of technological innovation. People are governed by the

bureaucracies they deserve.

Viet Nam was not an isolated historical event. It was a progression. Rather, a

focal point of a progression. Warfare, once defined as an extension of diplomacy, has

reached the point where it is recognized for what it is. Suicide on a mass scale. A drama

played out by individuals on a grand scale. There is no good, no bad. No manifest

destiny to be fulfilled. War is killing. It is not the passive act of dying. It is the

dynamic, purposeful, premeditated act of killing. Viet Nam played like a coming

attraction for high-tech war.

The high-tech world is one in which the language itself is a kind of shorthand.

The words and acronyms convey precise meaning to the participants and leave the

uninitiated struggling to comprehend. So it is with Viet Nam.

Viet Nam was high-technology warfare. High-technology war implies killing and

being killed without ever seeing the enemy face to face. It makes no difference whether

the means are NASA technology or bamboo technology. The result and effect are the

same.

Survivors remain victims by their own choice. Survivors purchased Viet Nam as

a book of direct experience. To read, to relive that volume as a nightmare, or as a

reference manual for formulating an insight into living, is also a choice. As it is for the

survivor, so it is with the nation.

Survivors are people specifically trained and well schooled at working effectively

in small groups. The groups that merged and diffused while maintaining their own

integrity. In a world of national unions and multi-national corporations, why would an

entire generation of Americans participate in an experience that prepared them so well

for quick, incisive reaction to immediate situations? I suspect that we will find out.

Isn't there something tragically humorous about a nation that had the audacity to

export its culture in the Peace Corps also manufacturing the experience of Viet Nam?

Would it change our perspective to consider the military in Viet Nam as a Peace Corps

with weapons?

The seeker and the knower have different, seemingly irreconcilable perceptions of

Viet Nam like the snapping of a large rubber band. The seeker sees the rubber band.

The survivor feels the snap.

When Our Troops Come Home

The survivors who were able to "adjust" were those fortunate enough to find a

person who sensed that beneath the actions and words of anger and resentment was a

consuming need to experience, to re-experience love. Love at the same level of intensity

as it was experienced during the survivor's lifetime in the mountains, jungles, and

swamps of Viet Nam. The need still exists. The need is growing. Both the seekers and

the knowers are beginning to have an awareness of the need to share the experience of

survival.

The problem with scientists' petitions for peace and disarmament is that they don't

have the armies necessary to enforce them. It is totally in character that as descendants

of Aristotle we maintain that war is justified to preserve peace.

Guilt, that insidious, non-specific, anxiety-provoking, persistent, American

symptom still infects our consciousness. Like a low-grade infection. The guilt of

sending. The guilt of going. The guilt of not going. The guilt of coming home. Like a

never-ending public crucifixion.

For the observer, the seeker, time is organized along the linear span of yesterday,

today, tomorrow. Past, present, future. Events, experiences perceived and organized in

relation to linear time.

A society so intently focused on time, schedules, todays and tomorrows was not

prepared to integrate the thousands of survivors whose perception of time was forever

altered by Viet Nam. From a world of untime the survivor was transported to a place

where a gold wristwatch is a status symbol.

For the knower, the survivor, linear time has little meaning. The survivor

experiences time through the association of intense emotions. Events, actions, music,

words, sounds, smells and situations in the present trigger a reliving of the past. And in

the moments of the reliving there is no past or present or future. There is only the

knowing.

Seekers would hope to find definitions, stereotypes and prior experience to

describe, specify, define Viet Nam. In prepackaged America, Viet Nam was not a

K-Mart war.

The seekers suspect. Survivors know. Peace is not a state of unwar. Peace is

Peace. War is War. We assume we cannot live with war. We are unwilling to choose

peace. We face death by default.

Science, the capacity to conduct high-technology warfare, and the governments it

perpetuates have their egos invested in quantified, measurable, physical reality. As a

creature of physical reality, man is most comfortable dealing with events, activities and

situations that can be physically manipulated. National policy is an extension of the

research laboratory.

When Our Troops Come Home

The fear of success has been identified as a personal anxiety for Americans.

Could it be that its national corollary is a fear of peace? War, the preparation for, the

diplomacy to prevent, and the anxiety over, is an active, energy consuming process that

can be pursued in the manipulation of physical events. War is a logical, technological,

masculine process.

Peace, the actual attainment of peace, not unwar, is threatening. It is anxiety

provoking. Peace is a state of being. An intuitive awareness. Peace is. Peace requires

no physical manipulation to maintain. We have no technology for peace. No wonder we

are so afraid of it. Peace is un-American.

If the seeker would know what a nuclear confrontation is at a personal level, ask a

survivor what it is to survive the detonation of an antitank mine. At the personal level

there is no winner, no loser. There is only survival. In a high-technology war all the

munitions are labeled "To Whom It May Concern".

The question currently posed is whether the American people can survive the

transition of their own government from a belief in war to a belief in peace. As, with the

survivor, for whom the war is not over, so it is with the structure of our national psyche.

Mediocrity is not moderation. Just as unwar is not peace. It will be interesting to

see if America has the character to live in moderation. Viet Nam was a real life fantasy

where the individual lived out his greatest fears and aspirations. An "other time" where

all that was best and worst in America's children displayed itself in a multi-dimensional,

quadrisonic, mosaic.

From observation and insight, Newton postulated that for every action there is

an equal and opposite reaction. His mathematical proofs laid the foundation for classical

physics. From classical physics through the quanta to the nuclear age. How would our

world be different had Newton formulated the proofs that for every action there are an

infinite number of equal and opposite reactions?

For all of us, the knowers and the seekers, this is an invitation to accept. In the

quiet of our time here, to understand that we are all truly survivors of Viet Nam.

When Our Troops Come Home

PART II

THE ICEMAN

When Our Troops Come Home

Chapter 5

"Here is a test to find whether your mission on

earth is finished: If you're alive it isn't."

Richard Bach

Illusions

"…His unswerving commitment to his duty and his unselfish sacrifice are a credit

to himself, his unit, and the United States Army."

The words came forth with no conscious effort. How many times have I heard the

words? How many wives and parents and children heard the words? The starched,

neatly folded American flag presented to them formally. The three volleys of seven shots

fired and echoing in the distance. The loss, the hurt, the desperation, the disbelief set to

music as a long bugler plays taps. And the feeling described so well in a song from long

ago settles on me, "Is that all there is?" Even now, the feelings come without the words

to express them.

What do I have to say to the parents who lost their child, to the wives who will

never feel their husband's arms around them again, to the children whose fathers never

came home? I'm sorry?

Wasted. A shorthand term for the act of killing. A synonym for the dead. A term

based on the assumption that a person's death had even less meaning than their life.

My daughter is two and a half. Children are very profound people in small

bodies. Jenny had not spent time along a mountain stream before. A week ago we went

to one.

We stood on the bank next to a fallen tree. The trunk created a quiet place in its

own backwater. It wasn't long before Jenny discovered throwing pebbles into the eddy.

I watched, enjoying her play, caught up in her pleasure of discovery. The untime of

perception. There were green, growing leaves. The sharp taste of pine needles.

The motion of running water. The quiet caring of the sunlight.

I looked out into the stream. It's springtime and the melting snow forced the

current irresistibly downstream. I looked at Jenny. Pebbles ready, concentrating on the

task at hand. The stream moved on. The water didn't seem to care whether or not a

Three-year-old threw pebbles in its way. And I realized what I knew. She was changing

the course of the stream forever. Minutely. Infinitesimally. Microscopically. Yet

irresistibly. The stream would never flow quite the same again. It didn't seem to care, its

surface moving on, and it was changed.

"Daddy, are you sad?" "No, sweetheart. I just love you very much."

When Our Troops Come Home

Those men were not wasted. Lives are not wasted. Death is not wasted.

The manner of a person's dying is as meaningful as his life. The statement of a loved

one's dying changes us forever. The statement is important. I cannot be sure what those

men said. I am beginning to understand what I heard. Are you listening?

To the survivors whose sons and husbands and fathers did not come home, there

is something that is very important that you understand. Those men were family to us.

We loved them. When they were hit, we did everything in our power to keep them alive.

When a man went down it was like a child with a piece of meat stuck in his throat. The

reaction was immediate. It made no difference that dishes and silverware went flying,

that glasses spilled and bowls overturned. Somebody was there. We tried. We tried so

hard. We cared. We fought to keep them alive long enough for the dust off to get in.

We yelled and screamed and pleaded. We held them in our arms and prayed. They were

family. They were a part of us. We loved them. And sometimes there was nothing we

could do. They had already decided. But they did not die alone.

When Our Troops Come Home

Chapter 6

"A man is rich in proportion to the number of things

he can afford to let alone."

Henry David Thoreau

Walden

Viet Nam survivors seldom talk about their experiences. How do they verbalize

the rancid, stinging, spoiled, ammonia stench of the sun baked dead? How do they speak

of the intuition of the ambush they walked into? How do they convey the unspeakable

process of growing old in a young man's body? How do they bring the awareness of

knowing to rational conversation?

The survivor knows absolutely that it is possible to care without feeling. The

survivor reads people's souls in their eyes. "What you're saying is so heavy," the lady

said. "There must have been some funny things. Some humorous experiences. Tell me

about the countryside. The people. Your friends."

"Do you know what I did?" responded the survivor.

"No", the lady said.

The survivor was watching her eyes. Knowing, before he spoke, that the lady had

sand bagged her soul.

"I killed people. It was my job. I was very good at it. Sometimes it feels like

that's what I did the very best in my whole life. I killed people."

"You mean when they attacked you?" Her voice was toneless. Detached. Like a

teacher dissecting a frog in biology class. The survivor read her eyes.

"I mean, I ambushed them. I mean, I waited stone silent in a moonless, shadow

blackness and when they walked by me, I blew their lungs out with an automatic weapon.

They never knew I was there."

The next question was unasked. It swelled in her eyes like a wino's vomit.

"You mean it wasn't a fair fight?"

The question thumped against the survivor's chest. An unexpected medicine ball.

It had simply never occurred to him that anyone would conceive of Viet Nam as a fair

fight.

When Our Troops Come Home

The lady's eyes dropped to her folded hands. The survivor studies the texture of

the tablecloth.

"We were talking about how I feel," he said. "Do you really want to know where

my feelings come from?"

And in the silence that followed, the lady's eyes never left her hands. "No.

No, I don't think so," she whispered.

The survivor had been home from Viet Nam for 15 years. The lady was his

mother.

Caring without feeling. Caring so much they will not feel. Caring without

feeling. Original sin. Caring without feeling. Sinners condemned. Survivors.

When do the tears come? What triggers the release? How do we heal the

wounds? The yelling, the screaming, the pleading, the praying. They aren't enough.

How do we heal the wounds? How do survivors heal themselves?

Is it the uncried tears that are necessary? The tears that hover at the brink so often

and are stoically withheld. Why not just find a quiet place and cry? Alone. Together.

Is it because the survivors are afraid they'll never be able to stop?

In Viet Nam no one ever looked down on a man who cried. The tears were

accepted. Acceptable. Crying was a part of the experience. There were times when the

situations, the feelings, were so overwhelming that the tears were the only link with

reality.

What's different now? Do survivors care less? No. I think they care more.

But thinking is not feeling. Survivors have worked very hard not to feel. They have

carefully, arduously constructed a state of emotional amnesia. Years of diligent effort,

day after day, to create the ramparts of objectivity. The survivors have forgotten the

feelings crouched waiting behind those walls. The survivor has chosen to forget.

Survivors fear feelings. Afraid of the lethal, pent up power. Like a waiting

claymore. The survivors fear disability. Released feelings may assault the very structure

of their life. The vulnerable person inside the carefully constructed, analytical, logical,

facade may be swept away. The survivors fear for their lives.

When Our Troops Come Home

Chapter 7

"Before I went over I knew a couple of friends that

came back. I asked, 'What was it like?' and they

didn't know how to explain it and I didn't

know what I was asking."

Al Santoli

Everything We Had

Day by day. Moment by moment. Casualty by casualty. Body by body.

The survivors began to freeze their emotions. At first we thought a wall was good

enough. We still cried. Cover. Protection. These were the first order of business for the

survivor. Profanity became the shorthand to express emotions. Humor. Laughing too

loud and too long at nothing. From physical vomiting to the emotional dry heaves was a

relentless progression for the survivor. Viet Nam evoked a vernacular of profanity not

only in the delta and highlands, but also on the college campuses.

The walls built to contain the hurt and pain and rage and desperation were not

enough. Walls could be breached. Walls could be broken. The individual could still be

reached. The neurological circuits began to overload.

The tracheotomy performed in the dirt with a pocketknife and the hollow bottom

half of a ballpoint pen began to take its toll. Walking through the villages, where

children and pigs lay side by side after the artillery lifted, left its mark. Being ambushed.

Being mortared. Incoming rockets. Friends simply vanishing, either on dust-off

choppers or in body bags, never seen or heard from again. The fatigue. The endless

tiredness. And finally the one situation, the single moment, the last ounce of bullshit.

The day the dry heaves stop. The fuck it day.

The day the circuits finally short out. Snap! That's it. That's just fuckin' it!

On that day the earth's axis shifted. What was tropical became arctic. The tears,

the puking, the feelings froze. In an instant. The day hell froze over.

The final, ultimate acceptance that feelings do not alter the situation. The day the

survivor reached a knowing that his own feelings were more dangerous than incoming

fire. The recognition that feelings make no difference. Killing makes no difference.

Dying makes no difference. The wounded make no difference. Ground taken, villages

burned, the body count, make no difference. It don't mean nothin'.

And all the hate and rage, all the love and hurt, all the caring and concern are

summed up in that one unacceptable, and profoundly simple statement: "Fuck it".

When Our Troops Come Home

The naïve, young warrior had become a death broker. He has assumed the

perspective of a survivor. The Ice Man. His only function was to get himself and as

many of his people as possible out. Whatever it took. The player who had given his all

and suddenly realizes that the game was rigged before he ever took the field. Someone

had bet on the point spread. The point spread that would become known as Peace With

Honor.

The reality was a piece of shrapnel in the throat. The reality was a piece of a leg

blown off. The reality was a piece of a lung shot away. The reality was a piece of paper

marked "remains nonviewable". The reality was a piece of the survivor's soul. Piece

with Honor?

Each survivor experienced that day. For me it was the day three seven blew. For

another survivor it was listening to his friend trapped inside the cockpit of a B-52 going

down over North Viet Nam.

Emotional cryogenics. The survivor imploded. Like a star collapsing on itself.

The black hole. The event horizon at its edge where time stands still. No yesterday.

No tomorrow. Only the here and now. Only the knowing.

Survivors do talk about Viet Nam. It's the intensity of their language that's

unacceptable.

When Our Troops Come Home

PART III

THE JOURNEY

When Our Troops Come Home

Chapter 8

"Morale is the greatest single factor in successful

wars."

Dwight D. Eisenhower

June 23, 1945

Forgiveness. Acceptance. Thawing. Who will forgive the survivor for the

enormity of his acts? Who will accept the primordial intensity it takes to remain

unfeeling? Who is prepared to accept the deluge of tears that must accompany the

thawing? Forgive? On what basis? With what justification? The survivor stands

convicted by his own actions. By his own memories. Guilty as charged. How does the

survivor admit to his family that he is guilty of acts and feelings, which, in any civilized

country on earth, would be met with prison if not summary execution? Murder. Arson.

Assault and battery. But we elude the real question. How does the survivor admit such

actions and feelings to himself?

The survivor learned his emotional lessons as a child. He internalized them on

his fuck it day. Big boys don't cry. Crying never solved anything. Stop crying or I'll

give you something to cry for. When tears become unacceptable, then what? Fuck it!

Sometimes the survivor tries to pretend he was a supply clerk in Saigon. A typist

at Cam Rahn Bay. The survivor uses "other time" to try and create alternative memories.

It doesn't work.

My oldest son played basketball on a junior high school team this year. One of

his teammates was a Viet Namese boy. A good athlete. Quick. Agile. Assertive. Built

well for his age. Muscular. Especially his legs. I would go to practices and games and

watch him. Watch his legs. Fascinated. Absorbed. Fixed on his legs. I could never

bring myself to say hello. His legs were those of the VC and NVA I killed. Muscular,

sinuous legs. From the weeks and months of humping equipment down the Ho Chi Minh

Trail. I wanted to say hello. I needed to say hello. I hurt to say hello. Could I forgive

myself? Would he forgive me? I have not yet said hello. Fuck it.

I just want to go home.

When Our Troops Come Home

Chapter 9

"… This made the Viet Nam conflict symbolic,

even mythological, from the outset. The ideological

battles eventually became more real and substantial

than anything taking place in the field, which placed

the combatants in grave danger, for they were not

trained for mythological warfare."

Walter H. Capps

The Unfinished War

Guilt is the morea eel that lurks in the crevices of my mind. Waiting. Waiting to

tear my throat out if I ever make the mistake of swimming too close. Guilt is the slimy,

gooey slug that wanders endlessly across the trails of my memories. Guilt is the metallic

shades of brown and green covering the skin of that huge snake coiled on the tree limb of

my imagination. The snake ready to drop and strangle the life out of me in a careless

moment. Guilt is the black shiny eyes of a starving rat hiding just beyond the door of my

consciousness. Guilt is the death stare of an opossum squashed on the highway leading

to my dreams. The death grimace. The bared teeth. Guilt is the tapeworm in my soul.

Know how to get a tapeworm out? Starve yourself for two or three days. Open

your mouth and hold a piece of food just in front of your teeth. The tapeworm slithers

out of your stomach and wriggles up through your throat, attracted by the food. Grab it.

Inch by slimy, putrid, retching inch pull it out.

That's what guilt is. Guilt is disgusting. Guilt is loathsome. Guilt is disabling.

Guilt is the cancer of the spirit.

For the survivor guilt is like having too much to drink. Needing to vomit and not

being able to. The survivor searches for the emotional equivalent to shoving a finger

down his throat. The release of being able to puke and collapse. Guilt is the

wheelbarrow in which we carry a whole wardrobe of other feelings. Insidious costumes.

The trappings of evil and dangerous men. Men who have the potential for violence.

Men who cannot be trusted, especially alone with their own feelings.

Look at this. Look at what's in here. Ah, here's the ensemble of aloneness.

Unworthy, unlovable, unforgivable. When I wear these I am most detached. No one can

see me. Least of all myself. The secretive attire of the stuck, powerless, guilt-ridden

victim. The survivor.

Who packed this bag? Are these the clothes I chose for myself? Looking at

what's in here, item by item, I'm appalled by my own creativity. Why do I keep them?

The rational, conscious me has no idea. The addict knows.

When Our Troops Come Home

The adrenalin addict knows. That camouflaged, face-blackened, cold-eyed, fleshconsuming addict knows. For he is the one who dominates my "other time". The one

who seeks the rush from reliving the moments of pain and exhilaration. The addict who

fabricates illusions of aliveness on the never-ending stage of my memories. I must keep

these costumes. I must keep them with me always. For how else can I conceal my real

nature in a world of nonusers?

Guilt, the habit of the priestly order of the Ice Man. Savored, luxuriated in,

retained as the last vestige of a time that history would rather forget.

Look at it. Look at this thing we call guilt. Look at it in the light of your own

awareness. Disgusting, maggot-infested, putrid, stench-filled guilt. I've shown you

mine. What about yours?

Remember how we found Charlie in the bush? We went out wandering around

until we got hit. It was stupid. Walking through the bush, wanting to get even, just

waiting to get blown away. Why? So we could call in the gun ships or tac air or fire

support and smoke Charlie before he got us. When you think about it, doesn't that pull

the hair on your leg a little bit? Live bait. Live goddamn bait! So pumped on adrenalin

and rage that, even though we knew better, we went anyway.

And for what? To come home and find out we were warmongers and murderers?

Killing and dying in a place we had no business being. Remember? Everybody said so.

And we began to believe it. Even the people who agreed to send the troops in after

Tonkin Gulf said we didn't have any business being there. An immoral war they called it.

As if there was any other kind. Shit.

The war we could never win. That's bullshit too. I remember a friend saying that

his unit wasn't losing when he left. Well, we weren't losing when I left either. We were

kicking Charlie's ass. We were getting hit. We were losing people. We were tired and

exhausted. But we were there. Every damn day we were there. We got blown up and

shot and burned, but we were there. We gave everything we had to keep our people

alive. We did the very best we could. Goddamn it! We were not losing in the field. Not

when I came home. Not when any of us came home.

I am really tired of pushing the wheelbarrow load of bullshit around that smells

like a loser when I know I did the very best I could. Just like you, I gave every goddamn

thing I had!

Angry? You're goddamn right I'm angry. Somebody had to be responsible for

Viet Nam. Have you ever heard anybody stand up in public and say, "I'm responsible for

this?" Have you ever heard a Congressman or a Senator or President say "I'm

accountable for what happened over there?" Maybe they did and I missed it. I haven't

heard anybody say it lately. You know what happened? You and I were the ones who

did it. We pulled the trigger. We called in the air strikes. We leveled the villages. We

When Our Troops Come Home

killed the civilians. You and me. The people in the bush. We did it. Accountability by

default.

You want accountability? All right goddamn it, I'm accountable. Me! I did it.

I was sent there to kill people and I did. I was responsible for keeping my people alive

and I did my very best. Many times my best wasn't good enough. And I'm sorry. You

want somebody who's responsible for the death and carnage? Okay you got it. It's me.

Me, goddamn it! But I'll tell you one thing. I'm not pushing this load of bullshit one step

farther. Not one more step. They can take this load of guilt and shove it! And there's

something else. There's nothing anyone can say or do to me that will be any worse than

what I've already said and done to myself.

I quit. I'm going home. My wife needs me. My children need me. And I need

them. Fuck it. I'm going home.

When Our Troops Come Home

Chapter 10

The softest thing in the universe

Overcomes the hardest thing in the

Universe.

That without substance can enter

where I know the value of non-action.

Teaching without words and working

without doing

Are understood by very few.

Lao Tsu

Tao Te Ching

Isn't it quiet here? This place called acceptance. Clouds forming effortlessly.

Quietly going about the business of being clouds. Constantly moving, ever changing.

Energy free to be itself. Content. Accepting. Isn't it quiet here? Moving through the

mist. Peaceful. Going home.

Isn't it strange what acceptance can do? Pastels envelop me. Warm, feeling

textures that radiate aliveness in a way I have not known before. I wonder who the

decorator was? Marshmallow substance clouds. A soft place. A place that simply is.

A strange, wonderful, alive place. This place called accepting.

"No, wait. I can't go home yet. It's too fast. Too easy."

"Ken?" A voice from nowhere. Everywhere.

"What?"

"Why can't you go home?" No one else here. Just me and the clouds. And the

voice.

"Because I haven't been forgiven yet."

"Don't you think accepting is enough?"

"How could it be enough? There must be some kind of penance to pay.

There must be something more intense than just accepting.

"I thought you left your load behind."

"Well, I did. But it can't be this easy. What about all the killing and suffering?"

"What about it?"

When Our Troops Come Home

"I must need to be forgiven. Don't I?"

"Look around you, Ken. What do you see? What do you feel?"

"I don't see anything. There's nothing here. Just these clouds. And the only thing

I feel is a breeze on my face."

"Do the clouds need to be forgiven? Should the breeze apologize?"

"What? What kind of question is that? How do you forgive a cloud? Forgive it

for what? Forgive the breeze? The questions don't make any sense."

"Haven't you seen what clouds and wind can do, Ken?"

"What?"

"Haven't you seen the smoke and flames of the forest fires started by lighting

exploding from the clouds? Haven't you seen the winds rip homes and buildings apart

leaving people dead and homeless?"

"Well, sure. But those were thunderstorms and hurricanes. What has that got to

do with me?"

"Don't the clouds and wind need forgiveness?"

"This is crazy. Why would I have to forgive the wind and clouds? It's not like

they destroy things on purpose. It just happens sometimes."

"Ken?"

"What?"

"What makes you think that you are any different than the clouds and the wind?"

"Are you telling me that accepting is enough?"

"For now…. If you are willing to let it be."

"But I'm a man. A human being. I can't go around killing people and just

accepting my way out of it."

"That's true. You are indeed accountable. Understand, too, that whatever you

were, whatever you did, the price has been paid. If forgiveness is so important to you,

then you are forgiven. Forgiveness is something that must be accepted too. Do you

understand what you know?"

When Our Troops Come Home

"Can I go home now?"

"Please do. They're waiting for you."

I can feel the voice smiling. Leaving.

The clouds are drifting away. The earth feels solid and warm beneath me.

Drifting, moving, parting clouds. It won't be long now. Quiet. Feeling. Caring. No

longer empty. Peaceful. Content. Accepting. Going home.

Do you see them? In the distance there. Waiting. The people I have missed so

much. The people I ached to be with. Do you see them? It won't be long. They're

smiling. They've waited so patiently. My sons, Garon and Ryan. My little girls, Jenny

and Jillian. They're smiling. Their daddy is coming home. And Peggy, my wife, my

best friend. Fifteen years we've been together. Fifteen years she's been waiting. Waiting

through the dreams and flashbacks. Waiting through the long silence. Waiting through

the darkness. Patiently waiting. "Peggy?"

"Yes, Sweetheart."

"I made it."

"I knew you would, Ken. I love you."

When Our Troops Come Home

PART IV

THE MEDUSA

When Our Troops Come Home

Chapter 11

"… 'Come here and I will show you the punishment

given to the famous prostitute who rules enthroned

beside abundant waters, the one with whom

all the Kings of the earth have committed

fornication, and who has made all the population of

the world drunk with the wine of her adultery.'"

The Book of Revelation

Chapter 17: Verse 2-3

Will you sit with me awhile? I'm here in my place again. The brightly lit, open,

airy, family atmosphere of the local pizza parlor. Gracious people here. They've

reserved my table. The one in the large back room where the children's birthday parties

and little league award ceremonies are held. The table in the farthest corner with wood

paneled walls on two sides. My table. The safest table in the restaurant.

It's mid-February 1984. A year since we last talked. A year, can you believe it?

Twelve months that vanished in a blur and lasted forever. I "came home" about this time

a year ago. In the interim I have learned that coming home is not being home.

The ghosts came with me. And with the ghosts come the feelings. Guilt. Anger.

Aloneness. These fluid, filmy, vaporous entities that hover around the brink of my

consciousness.

We talked about the wall. The breastworks built to constrain those feelings.

This has been a dismantling year. I have been spending my time unbuilding the wall.

Quietly. A brick at a time. Chink. Chink. Chink. The gnarled dusty, broken-fingernail

hands of the stonecutter. One day at a time. Excavating. Finding bits and pieces of

myself.

I've read books about Viet Nam; each one a writer's conversation with himself

that can finally be shared with those willing to listen. And I have come to understand

why I have so diligently avoided the novels about Viet Nam. As I suspected, it is in

those pages that the images of the ghosts reside.

I have discovered something else in this past year. I have fought it, railed against

it, shouted obscenities in its face. I have discovered that coming home is only the first

step in the journey. Coming home is not the same as being home.

She slips seductively through the shadows. The sound of silken motion.

The faintest echo of her footfall reaching deep inside me. Her image, her sound, her

fragrance, calling me. The most alluring woman I've ever seen. Dimly, barley

discernable, the flickering light from a distant source silhouettes her body. Lithe.

Enticing. Her suggestion communicated with inaudible clarity.

When Our Troops Come Home

The woman. The most beautiful, supple, desirable woman I have ever

envisioned. She wants me. She has chosen me. Magic in her movement. Her breasts

rising rhythmically with each breath. Her slender waist and rounded hips tapering to the

inviting, invisible solidness of her thighs. Long, slender, silk-enshrouded legs. Her

ankles and golden sandals intermittently seen through the swishing of her translucent

gown. Raven black hair accenting the contours of her bare shoulders. The amber depths

of her eyes reflecting my desire as I approach. Cunningly sultry. She conveys the purest

essence of woman. The woman all men seek. The woman beyond the woman seen

monthly in our magazines. She's there awaiting me in the vivid, muted colors which are

beyond the limitations of the photographer's lens.

Beguiling, seductive, wanton. Waiting there for you. Can you resist her, young man?

Don't you want to come with her?

When Our Troops Come Home

Chapter 12

"Being self-taught, they cannot be expected to show

any gratitude for culture they never received."

Plato

The Republic

November 1982. The Seattle-Tacoma Airport. The Horizon Club is a lounge

area that Western Airlines maintains for people awaiting flights. The club is separated

into three sections. The entry contains a reception desk and small bar area. Four lounge

chairs arranged in pairs, facing each other, with small tables between them. Beyond is a

larger room. The television stands watch here. A sofa and some over-stuffed chairs sit in

attendance. The third area is for phone calls. Sofas back-to-back in the center of the

room, facing the chairs next to the walls. Three phones on tables between the semicomfortable chairs.

It's late afternoon. The drizzle turns to rain against the windows. For most of us

here it's comfortable enough. About as comfortable as possible for bodies in transit.

Lounging people, reading people, waiting people. The television mumbles on. Six

o'clock. News time. Who cares? I put my magazine down and withdraw to the phone

near the back wall. Time to call Peggy and let her know when I'll be home.

The phone call is completed. Relaxing now. Settling in. Everything is fine at

home. Peggy has a way of bringing back my smile.

The atmosphere has changed. There's static in the air. A fingernails-on-theblackboard sensation. A commotion in the TV room. The strained, restrained voice

grasping at me.

"You don't know what you're talking about. Why don't you just shut the hell up!"

What's going on? A man moving toward me. Moving faster than the

accommodations would dictate. An angry man. Conversations have stopped. The TV

commentator drones on, concluding his nonstory about Viet Nam. The man excuses

himself as he passes in front of me and sits heavily in the chair next to mine.

Quick impressions. Six feet, one. A hundred eighty pounds. Age? Early thirties.

He looks solid in his brown tweed sport coat and tan slacks. A business traveler. The

open collar of his pale blue shirt conferring an attitude that he's more concerned with

doing business than impressing anyone. Seems like a good man to have on your side.

He's hurting, though. Struggling to gain control. I know the feeling. He'll be OK.

The apparition appears. A young man. A kid. Neatly tucked into his blue, threepiece, dress-for-success ensemble. Frail, almost anemic looking. Energetic. An

When Our Troops Come Home

energetic anemic. Blonde hair prematurely thinning. Wire rim glasses. A plastic smile.

He has to be either an actuary or a Yale divinity student. I don't know who he is and

already I hate him.

My man looks up from the chair beside me as the neoprene person slides by me

and takes up a position on the couch facing us. A ragged voice speaks from my friend.

"I was out of line. I apologize."

Plastic man won't let it be.

"Oh, it's OK. Gee, you feel very strongly about Viet Nam. I'm really interested.

I studied the war in my political science class."

My friend is struggling again.

"Look, I'm really sorry. Why don't you go back and watch television?"

The kid is either totally insensitive or incredibly stupid. Maybe, probably both.

The conversation rambles on. The academician posing long, involved, philosophical

questions about war and social justice. My friend's responses are clipped, constrained

variations of yes or no.

The mouse is enthralled with his own dialectic. My friend is enduring. He made

the mistake of giving his position away and he's paying the price.

Me? I'm just sitting. Legs crossed. Hands folded in my lap. Watching.

Thinking about how may different ways you can kill someone with a newspaper.

The kid really doesn't understand what he's dealing with. How could anyone be

so naïve? He doesn't realize how close to the edge he is. Rambling on and on. Words.

Overused words. Unmeaning words. Like a child picking the scab on a mule's leg. If he

picks long enough, if he picks deep enough, if he draws blood, he's going to get the shit

kicked out of him.

The receptionist walks back to announce a flight departure. My flight. Come on

back, Ken, you've got a plane to catch. I stand up to leave, and hand my business card to

my friend.

"I was there," I offer. "I'll be in my office tomorrow morning if you want to give

me a call."

"Thanks," he says.

Saturday morning. Alone at my desk. The phone rings.

When Our Troops Come Home

"This is Ken Jones."

"Uh, Mr. Jones, I was at Sea-Tac yesterday…."

"I know. Did you kill that son of a bitch?"

"No, I let him skate."

"Yeah, too bad…."

My friend had been a Marine lieutenant in I Corps. An infantry platoon leader.

We talked for two hours. The first person I had really talked to about Viet Nam since I

returned.

I don't even remember what we talked about. I just knew that I was talking with

someone who spoke the language. Another person who needed to talk.