Vanity Fair by William Makepeace Thackeray BEFORE THE

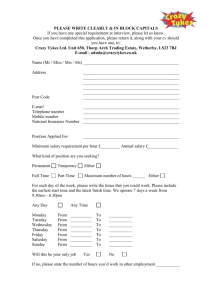

advertisement