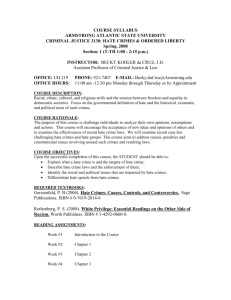

Psychological Effects of Hate Crime – Individual Experience and

advertisement