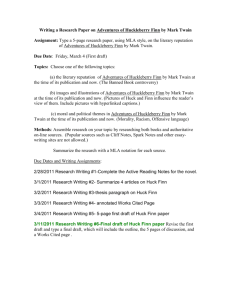

The Burden of Huckleberry Finn

advertisement