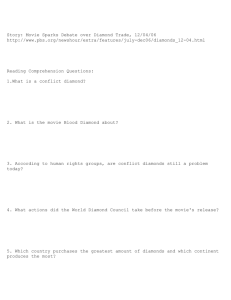

Kauffman case study 2 - K-12 Program

advertisement

THE NATION’S NEWSPAPER Collegiate Case Study www.usatodaycollege.com Web puts undiscovered musicians, listeners in tune Technology & Entrepreneurship By Kevin Maney Innovation drives America’s economy and fuels its competitiveness. Henry Ford exemplified this by channeling his affinity for mechanical equipment into the development of the self-propelled Quadricycle and the Model T, the first affordable automobile. Today, transforming an idea into an entity relies on innovative technology and has led to such mind-boggling creations as digital music, RFID (radio frequency identification) and man-made diamonds. This case study explores the various ways technology impacts entrepreneurship. How do the challenges and advantages of being an entrepreneur in the 21st century differ from being one in Henry Ford’s time? Read these articles before you answer. ...................................................................................3 Man-made diamonds spark with potential By Kevin Maney ..................................................................................4-6 Books might have to start new chapter to avoid extinction By Kevin Maney ..................................................................................7-8 Band's Net-inspired hit shows how EMI goes with the flow Scared of new nano-pants? Hey, you may be onto something By Kevin Maney USA TODAY By Kevin Maney NEW YORK — You know you're at a record company when there is a piano in the reception area. ........................................................................................9-10 Case Study Expert Karen Thornton University of Maryland ......................................................................................11-12 USA TODAY Snapshots® Top tech items Nearly half of respondents say they are likely to buy technology products within the next six months for when they are on the go. Top technology items to be purchased: Cellphone 17% Camera Laptop compu ter Personal mus ic device 8% Video camer a 14% 10% 7% Source: Harris Interactive online survey of 1,174 adults age 18 and over. Margin of error ±3 percentage points. I'm here at EMI Music to see a record company executive. The industry has taken a beating the past five years. Last week, numbers released by Nielsen SoundScan showed the industry heading for yet another full-year slump for 2005. Everybody in tech talks about how the record companies don't “get it.” But nobody ever seems to talk to the record companies to see what they don't get. So here I am, expecting to meet some techno-phobic dolt who calls everyone "baby" and aches for the days when American Bandstand mattered. He no doubt wears a scarf. Instead, I get Adam Klein, an urbane Brit dressed in gray corduroy pants and a gray sweater over a button-down shirt. He is EMI's executive vice president in charge of strategy. At one point before joining EMI in 2004, Klein had been president of search engine company Ask Jeeves. He owns a video iPod. Amazingly, given the portrayals of his profession, there is a computer on his desk. And it's turned on. Over the next hour, Klein does a couple of things I don't expect. First, he lays out how technology has created challenges for the music industry that go deeper than most people realize — certainly deeper than just the piracy of copyrighted songs. And then, instead of dwelling like a psychopath on how to stop piracy, Klein focuses on how the industr y is reengineering itself to get ahead of technology and start growing again. "It's unfortunate that the industr y allowed itself to be seen as Neanderthal," Klein says. "We're not asleep at the switch. It's just that of all the industries I've studied, none has had to deal with such a confluence of events." Actually, once Klein gets into it, you By Jae Yang and Marcy E. Mullins, USA TODAY © Copyright 2006 USA TODAY, a division of Gannett Co., Inc. All rights reser ved. AS SEEN IN USA TODAY’S MONEY SECTION, WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 2, 2005 wonder why the music industry hasn't collapsed like an ant colony that lost its queen. Certainly technology brought an unprecedented level of piracy, and it's hurt the industry. But that's only the beginning. Digital online music has forced the industry to re-examine its soul. "The record industry has never been consumer-centric," Klein says. Instead, it has always pushed content on people. If a label had a hot new act, it pushed songs out to radio and, later, MTV. It tried to dictate tastes and tell us what to buy and how to listen to it, instead of paying attention to what we wanted. This is how consumers wound up with eight-track tapes. And Toto. By Dusan Reljin But the Net puts consumers in control. Teens tell each other what to buy through podcasts and playlists posted on MySpace. They listen to songs on any device they want and use software to convert songs to the format they want. This is a massive philosophical switch for the industry, and, "We are just starting to look at the business through that lens," Klein says. What else? Well, the "retailers" — the entities through which music is sold — are changing, and they all have different business models that are foreign to anyone who's worked in music for the past 50 years. Mobile-phone companies might give music away to keep customers. Apple wants to sell music for less to drive the sale of more iPods. None of it works anything like an old-fashioned record store. At the same time, the industry is facing this challenge: 95% of its revenue comes from the sale of physical CDs, which from now on will be a shrinking part of the business. The industry's growth will come from digital sales, which are now just 5% of the business. So where do you put your resources? On the 95%, or the 5%? On top of that, a large swath of teenagers — among the industry's biggest customers — don't have credit cards. You need a credit card to buy music online. So the industry is selling to its best customers at stores at which they can't pay. The past couple of years, Klein says, the industry woke up and started a painful process of change. EMI has made huge investments in technology — computer systems, databases and digital storage it never before had to maintain. It has brought in a new set of people who, like Klein, are as grounded in technology as they are in music. It has decided its brightest future lies in music-subscription services such as Rhapsody and the new Napster. Those services are hard to pirate, and they eliminate the problem of kids not having credit cards. Brondell founder: Dave Samuel with the Swash electronic toilet. Underneath all that activity, record companies have had to really think about why they exist — and should continue to exist. What do they do best? Klein thinks he has an answer: "Developing and growing artists — that's what a music company will be doing," he says. Finding talented musicians, coaching them, putting them in front of the public — and then finding ways to profit from their work. Sell it online, sell it into video games or whatever new forms technology brings along. This is how the industry needs to think. Will it work? It's too early to tell. Industry figures show digital sales shooting skyward and the overall sales misery leveling out. Klein says it's a trough, and growth is on its way. Industry analysts tend to agree, to a point. Jupiter Research sees zooming digital sales replacing lost CD sales by 2010. While here, I get a glimpse of how a record company can learn to cope. EMI has a band called OK Go. It wasn't getting a lot of attention. Then the band shot a home video in a band member's backyard. It's just the four of them doing a goofy dance they made up to one of their songs. They put it on DVD and handed some out at their concerts. Next thing, the video started flying around the Internet. EMI ran with it, putting the video on the band's website, www.okgo.net. It turned into one of those Internet phenomena, exceeding 2 million downloads. OK Go did the dance on Good Morning America. The night I met Klein, I saw OK Go play in a New York club. As their encore, the band did the dance to a packed room of screaming fans. If the music industry can build on experiences like that, it might yet improve its Neanderthal image. Reprinted with permission. All rights reser ved. Page 2 AS SEEN IN USA TODAY’S MONEY SECTION, WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 7, 2005 Web puts undiscovered musicians, listeners in tune Artists used to need a record label to be heard. Now, all they need is a powerful PC and a broadband connection. By Kevin Maney USA TODAY For any musician with at least a pinch of talent and a desire to perform, the Internet has become a godsend. A new generation of websites — many of them started by people who came out of the music industry — are opening the business to thousands of artists and hobbyists who in the past had few ways to broadcast and sell their music. "Technology has changed things all the way through the chain," says Kelli Richards, a digital music pioneer who cowrote The Art of Digital Music. "You can, in a garage, create (recorded) music that 10 years ago would've cost $100,000, and you can instantly reach a global audience." Driving the changes are the increased power of PCs and broadband Internet. Independent musicians can now use a PC as a multitrack recording studio. Songs can be inexpensively created, stored, burned to CDs and uploaded onto the Web. Those websites can be much more than just a place to post songs in hopes someone might find them. Jenna Drey was an undiscovered dance-music artist who uploaded some of her songs onto GarageBand.com. The songs rose to the top of the website's listings, and Drey wound up with a record deal and a song that reached No. 11 on Billboard's dance chart. Even for a band that's more of a weekend hobby, the Web creates ways to get occasional bookings and sell CDs. Some types of independent music websites: u Discovery and development. There have long been a couple of problems with independent musicians posting their output on the Web. First, how would anyone sort through all that music to find quality songs they might like? And, second, how would an ordinary musician fight through the noise to get noticed? One solution: GarageBand.com. Any unsigned musician can post music on the site. Listeners are asked to rate songs. Ratings and traffic on the site drive songs toward the top of GarageBand's charts, which are much like Billboard charts. Listeners looking for popular music can go to GarageBand and check out songs at the top of the charts in categories they enjoy. labels. Magnatune, for instance, looks for talented but unsigned artists and is building a stable of acts, much like a record label. But Magnatune sells downloads and doesn't sign its artists to exclusive contracts. u Distribution and sales. Not long ago, there were few ways for unsigned artists to make any money on their work. But now, so what if you can't muscle onto record store shelves? Anyone can sell CDs through CD Baby, which has grown into the Amazon.com of independent music. Another company, Pump Audio, has figured out how to sell independent music to the creators of T V shows, commercials and movies for use as background music. Pump splits the revenue with the musicians. u Live events. Websites are starting to automate what a professional manager might do. Sonicbids, for instance, posts listings of venues seeking live acts and gives bands a way to reply by clicking and sending an electronic press kit. "There used to be only one way to get the job done: Go through a major label," author Richards says. "Now, the artist has a choice." Other sites act as online-only record Reprinted with permission. All rights reser ved. Page 3 AS SEEN IN USA TODAY’S MONEY SECTION, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 7, 2005 Man-made diamonds sparkle with potential Beyond the bling, they could usher in new tech age By Kevin Maney USA TODAY they've been held back because mined diamonds are too expensive and too rare. And they're hard to form into wafers and shapes that would be most useful in products. BOSTON — In the back room of an unmarked brown building in a run-down strip mall, eight machines, each the size of a bass drum, are making diamonds. Manufacturing changes that. It's like the difference between having to wait for lightning to start a fire vs. knowing how to start it by hand. That's right — making diamonds. Real ones, all but indistinguishable from the stones formed by a billion or so years' worth of intense pressure, later to be sold at Tiffany's. The company doing this is Apollo Diamond, a tiny outfit started by a former Bell Labs scientist. Peer inside Apollo's stainless steel-and-glass machines, and you can see single-crystal diamonds literally growing amid hot pink gases. This year, Apollo expects to grow diamonds as big as 2 carats. By the end of 2005, it might expand to 10 carats. The diamonds will probably start moving into the jewelry market as early as next year — at perhaps one-third the price of a mined diamond. The whole concept turns the fundamental idea of a diamond on its head. The ability to manufacture diamonds could change business, products and daily life as much as the arrival of the steel age in the 1850s or the invention of the transistor in the 1940s. In technology, the diamond is a dream material. It can make computers run at speeds that would melt the innards of today's computers. Manufactured diamonds could help make lasers of extreme power. The material could allow a cellphone to fit into a watch and iPods to store 10,000 movies, not just 10,000 songs. Diamonds could mean frictionless medical replacement joints. Or coatings — perhaps for cars — that never scratch or wear out. Scientists have known about the possibilities for years. But "I'm just so completely awed by this technology," says Sonia Arrison USA TODAY of tech analysis group Pacific Research Institute. "Basically, anything that relies on computing power will accelerate." Arno Penzias, a venture capitalist and Nobel Prize winner for physics, says, "This diamond-fabrication story marks a highprofile milestone on an amazing scientific journey." "We can't begin to see all the things that can happen because single diamond crystals can be made," says Apollo co-founder Robert Linares, elegant and slim in a golf shirt, slacks and loafers as he sits at the two plastic folding tables that make up Apollo's low-budget conference room. "We are only at the beginning." Linares has worked on the technology for 15 years, much of that time in his garage. From the start, he did this because of the promise of diamonds in technology. Linares wasn't trying to make gems. In fact, he didn't think he could. Then he had a happy accident. Well, actually, time will tell whether the accident was a happy one. Two different paths to diamonds In 1955, General Electric figured out how to use room-size Reprinted with permission. All rights reser ved. Page 4 AS SEEN IN USA TODAY’S MONEY SECTION, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 7, 2005 How diamonds are made Apollo Diamond is making real diamonds using a process called chemical vapor deposition (CVD). 2 Hydrogen and hydrocarbon gases are injected and heated to thousands of degrees under pressure. atoms land on the diamond slice and replicate the 3 Carbon crystal’s structure, the way a drop of water merges seam- lessly into a pool of water. The diamond grows thicker and taller. Growing a five-carat diamond can take a week. Gasses top can be sliced off and 4 The cut into gems. Or the diamond can be cut into thin wafers for computer chips or other uses. Part of the slice is returned to the chamber to make the next diamond. Carbon atoms of diamond is placed 1 Aflatslice inside a chamber. Source: Apollo Diamond By Robert W. Ahrens, USA TODAY machines to put carbon under extremely high pressure and make diamond dust and chips. The diamond material wasn't pure or big enough for gems or digital technology. But it had industrial uses, such as diamond-tipped saws. Such saws made it possible, for instance, to cut granite into countertops. In the ensuing decades, companies and inventors tried to make bigger, better diamonds. But they didn't get far. By the 1990s, researchers were focused on two different paths to diamonds. One was brute force. Some Russians became pretty good at it, and their machines were eventually brought to Florida by Gemesis. That company now crushes carbon under 58,000 atmospheres of pressure at 2,300 degrees Fahrenheit, until the stuff crystallizes into yellowish diamonds. The stones are attractive for jewelry but not pure enough for digital technology. Gemesis sells its gems through retailers at around $5,000 per carat. A mined yellow diamond can cost four times more. The other process is called chemical vapor deposition, or CVD. It's more subtle. It uses a combination of carbon gases, temperature and pressure that, Linares says, re-creates conditions present at the beginning of the universe. Atoms from the vapor land on a tiny diamond chip placed in the chamber. Then the vapor particles take on the structure of that diamond — growing the diamond, atom by atom, into a much bigger diamond. CVD can make diamonds that are clear and utterly pure. It's also a way to make diamond wafers, much like silicon wafers for computer chips. The CVD process can be tweaked by putting in enough boron to allow the diamond to conduct a current. That turns the diamond into a semiconductor. A handful of companies and scientists, including Sumitomo in Japan and the global diamond powerhouse De Beers, have chased CVD. But by most accounts, Linares is out front. After receiving his doctorate in materials science from Rutgers University, Linares joined Bell Labs and worked on crystals that would be crucial in telecommunications. In the 1980s, he started Spectrum Technology to make single-crystal Gallium Arsenide chips, one of the key components in cellphones. Spectrum became the material's biggest U.S. supplier, and Linares eventually sold the company to NERCO Advanced Materials. He then dropped out of business, putting his time and money into his pet project: making CVD diamonds for cutting tools and electronics. "Gemstones were the furthest thing from my mind," Linares says. Breakthrough in a garage workshop Linares built machines in his garage, superheating carbon in suburban Boston while his neighbors went about their lives. He got the CVD process to work, at first making tiny diamond chips. He formed Apollo and started down the path to industrial diamonds. Then Linares inadvertently left a diamond piece in a beaker of acid over a weekend. The acid cleaned up excess carbon — Reprinted with permission. All rights reser ved. Page 5 AS SEEN IN USA TODAY’S MONEY SECTION, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 7, 2005 essentially coal — that had stayed on the diamond. "When I came in Monday, I couldn't see the (stone) in the beaker," Linares says. The diamond was colorless and pure. "That's when I realized we could do gemstones." Both Apollo and Gemesis want to market their gems as "cultured diamonds," taking a cue from cultured pearls. De Beers is fighting that label. "It's misleading and unacceptable," says De Beers executive Simon Lawson. "It makes people think (manufacturing diamonds) is an organic process, and it's not." For Apollo, there are lots of good things about making gems. Diamond jewelry will be a $60 billion global market this year, and it's growing fast. If Apollo can snag just 1%, the company would become a $600 million rocket. Even highly trained diamond experts find it almost impossible to tell a CVD diamond from a mined one. De Beers is determined to help by making machines that can detect the slightest difference in the way the two materials refract light. Also, gems could become a source of revenue quickly. While the military and companies are working on tech inventions that use diamonds, a real market for diamond technology might be a decade away. By selling gems, Apollo can make money now to fund the research for forthcoming diamond tech products. As part of that effort, De Beers stepped up its own CVD research "focused on producing state-of-the-art synthetic diamonds for testing on our equipment," Lawson says. Referring to CVD diamonds, he adds, "We don't see gemological applications fitting into it." That solution, though, brings two huge problems. One is that Apollo doesn't know the gem business. Its employees are technologists. Aside from Linares, Apollo is run by his son, Bryant, an MBA who started and sold an information services company. Vice President Patrick Doering had been lead scientist at Spectrum. "We are not gemstone guys," Bryant Linares admits. They don't know consumer marketing or retailing. Bryant Linares notes that Apollo plans to split into a tech business run by the Linareses and a gem business run by a gem veteran they have yet to hire. For now, though, the gem business is a distraction with a steep learning curve. Apollo's other problem is De Beers, which doesn't like what Apollo is doing one bit. De Beers launched a public relations campaign and an education program for jewelers, all aimed at portraying mined diamonds as real and eternal -- and CVD or Gemesis diamonds as fake and tacky. So by getting into gems, little Apollo made a powerful, determined enemy. A long list of possibilities The tech side is an entirely different stor y. Just about ever y entity in technology can get excited about diamonds. The military's DARPA research arm has been pumping money into CVD projects. Companies such as Lucent are on the trail of holographic optical storage, which will use lasers to store data in 3D patterns, cramming huge amounts of information in tiny spaces. CVD diamonds would vault holographic storage ahead, helping bring about the 10,000-movie iPod. Tech company Textron is a big fan of Apollo. Textron has been working on super lasers that might become weapons or be used like a camera flash for spy satellites, so they could take photos from space at night. conductivity of any material, which allows it to quickly move heat away from the laser's insides. Textron needs large, pure diamond pieces for its lasers and finally found them at Apollo. CVD diamonds can help solve one of the computer industr y's biggest challenges. Companies such as Intel advance computer chip technology by squeezing microscopic wires closer together while making the chips run ever faster. But that's making the chips increasingly hotter. At some point this decade, the chips could run so hot they'd melt. But not if the chips were based on diamond wafers instead of silicon. "Using diamonds as semiconductors will continue Moore's Law," says Pacific Research's Arrison, referring to an observation about the continual increase in speed and power since chips were invented. The list of possibilities for man-made diamonds goes on. "By most measures, diamond is the biggest and best," says a research paper written about CVD by Paul May at the U.K.'s University of Bristol. It's the hardest material, it won't expand in heat, won't wear, is chemically inert and optically transparent, May says. "Once (manufactured) diamond is available, developers will find all kinds of other things to do with it," Rober t Linares says. Manufactured diamonds will be like other inventions that were so profound because they made new things possible. Steel allowed engineers to dream of skyscrapers and suspension bridges. Transistors led to computers and pacemakers and so much else. So this may be the beginning of the diamond age of technology. Says Linares: "The genie is out of the bottle, and it can never be put back in." "Thermal management is a major challenge to increasing a laser's power," explains Textron scientist Yulin Wang. The diamond has the highest thermal Reprinted with permission. All rights reser ved. Page 6 AS SEEN IN USA TODAY’S MONEY SECTION, WEDNESDAY, JULY 20, 2005 Books might have to start new chapter to avoid extinction By Kevin Maney USA TODAY Here's a really hard question: What is a book? It's hard, because for 500-odd years, nobody's had to think about it. A book has been a selfcontained unit of a lot of words on a good number of bound pages. But that might not be the answer anymore — or at least not the only answer. website, Doctorow encourages fans: "When you download my book, please: Do weird and cool stuff with it. Imagine new things that books are for. Then tell me about it ... so I can be the first writer to figure out what the next writerly business model is." He's not thinking that the future of books is simply reading book-length text on a screen instead of on paper pages. He's thinking it's something that happens when you decouple the content from the medium. In music, that kind of decoupling hasn't resulted in Over the past few days, Harry Potter and the By Kevin Maney people listening to the old concept of "albums" on Half-Blood Prince has flown off bookstore shelves, iPods or laptops. igniting the kind of frenzy seen in the past for Star Wars movies, Beatles concerts and the arrival of Beanie Baby Instead, people have been doing new things -- buying shipments. This Potter mania seems to disprove everything that individual songs, making mixes, sharing playlists online, pundits postulate about the downfall of traditional books. creating podcasts, dumping music into cellphones to use as ring Half-Blood Prince is 652 pages long. That's not a book — it's a tones. We are generally doing absolutely nothing that the music commitment. And its fans aren't just the usual book buyers — industry might've predicted a decade ago. pre-Nintendo people like me, who read because we're either The technology isn't here yet to make that possible with stuck on long flights or can't hear the TV from the couch. books. No screen has yet been able to beat traditional paper books as a display for lengthy text. But that won't be the case Potter is actually stealing kids away from video games. forever. A breakthrough for books with an iPod-level impact is But don't let that success fool you. Books overall are losing going to happen at some point. And then? the battle for attention, especially with anyone born after about "I think book is a verb," Doctorow says. It's what you're doing 1975. From 2003 to 2004, the number of books sold worldwide dropped by 44 million. True, there are still 2.3 billion books sold when reading something like a narrative story or biography or each year, but the bottom line is that people are flocking to the academic argument in big chunks in multiple sessions, he says. Web, TiVo, cellphone screens, PlayStation Portables and DVDs "We need to find ways to insert the verb of book into technologies that arrive," Doctorow adds. while buying fewer books. Books risk becoming the equivalent of pot roast in a world full of ethnic foods. There will always be a place for pot roast, but it sure isn't the place it occupied 30 years ago. To avoid that fate, the concept of a book might have to change. But how? Author and activist Cory Doctorow hopes to find out. In June, he released his latest novel, Someone Comes to Town, Someone Leaves Town, online for free downloads on the same day his publisher released printed copies to bookstores. On his Doctorow admits he hasn't yet learned a lot from his fans about what books can become. But there are some interesting hints. For instance, he's certain that the free electronic copies are helping increase sales of hard copy books, which is the opposite of what publishers and authors fear. "For almost every writer, the number of sales they lose because people never hear of their book is far larger than the sales they'd lose because people can get it for free online," Doctorow says. "The biggest threat we face isn't piracy, it's obscurity." For more educational resources, visit http://education.usatoday.com Reprinted with permission. All rights reser ved. Page 7 AS SEEN IN USA TODAY’S MONEY SECTION, WEDNESDAY, JULY 20, 2005 Potter might even offer a clue to how books might change — and, ironically, it could be in the length of both the individual books and the series. Now, keep in mind that Doctorow is still a lonely voice out on the frontier. Tom Standage, technology editor at The Economist and author of the recent A History of the World in 6 Glasses, says that traditional books will continue to do just fine. These books offer something movies or T V can't: a deeply involving experience that you live with for days or weeks or more. "Communications media are ver y rarely displaced by newer technologies," he points out. "T V did not kill radio, movies did not kill theater, video did not kill movies. The book is the oldest of all of these technologies, so I think it has staying power." "It's very typical to hear a (video) gamer say, 'I play to experience a world that I couldn't experience otherwise,'" says Mitchell Wade, who sur veyed gamers for his book Got Game: How the Gamer Generation is Reshaping Business Forever. Which, even if true, doesn't mean books won't change. Other media adapted to changing technologies. Radio couldn't survive airing shows like The Shadow once TV flooded homes with pictures. Live theater survived movies by emphasizing blockbuster musicals. Now movies might have to change in an era when millions of families can play DVDs on big-screen, high-definition TVs in their living rooms. USA TODAY "When you see kids reading the (Potter) books over and over, they are no longer in it to find out who done it," Wade says. "They are reveling in the world that J.K. Rowling has created. That is VERY like a video game." Of course, that's also because Rowling is so good at what she does. Still, if Harry Potter can show ways to keep an ancient medium relevant, that certainly would be magic. Reprinted with permission. All rights reser ved. Page 8 AS SEEN IN USA TODAY’S MONEY SECTION, WEDNESDAY, JUNE 22, 2005 Scared of new nano-pants? Hey, you may be onto something By Kevin Maney USA TODAY move until we have less privacy than the Osbournes. Or that genetically modified foods could make us morph like the Fantastic Four. Or that cellphones could be giving us brain cancer and are distracting drivers. In the late 1950s, my Uncle Jim and his teenage buddies would sometimes roam downtown Binghamton, N.Y., and stop at a little shoe store that had its very own X-ray machine. And yet an earlier generation thought dangerous X-rays were fun. What gives? It was the latest technology for getting your shoe size. Customers would come in, flick a switch, stick their feet in, and see how their foot bones lined up on a sizing chart. My uncle and his friends did this for kicks. The thing probably spit out hundreds or thousands of times the dosage you'd get from a dental X-ray today. As it turns out, these things go in cycles, and extreme reactions to technology are nothing new. "It's been going on as long as innovation has been going on," says Clinton Andrews, past president of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers By Alejandro Gonzalez, USA TODAY Society on Social Implications of It's a wonder Uncle Jim never Technology. "The guy selling the grew a few extra toes. innovation is often optimistic. But there's often this fear, and the fear is not entirely groundless." Contrast that with the naked folks in Chicago a few weeks ago. A handful of young men and women filed into an Eddie Bauer store and took off their clothes to protest the selling of khaki pants treated with nanotechnology. So far, there seems to be no reason to think anyone could be hurt by nano-pants, but a lot of people are terribly worried about nanotechnology. They've heard stories that it could selfreplicate until it covers the Earth like a virulent kudzu, or that nanotech particles might damage brain cells or cause cancer. They're assuming the worst now, ahead of any proof of danger. In fact, people today are raising all kinds of alarms about technology. They worry that RFID chips might track our every In fact, IEEE preaches that technologists should welcome the protesters and skeptics because they force issues to the surface early, before something gets out of hand and causes widespread damage. The fears push technologies to improve, and get society to look at consequences and decide what trade-offs are acceptable. "You always need both camps" -- the optimists and the pessimists, says Brian O'Connell, current president of the Society on Social Implications of Technology. Feelings about technology can also wax and wane with eras. In the 1920s, anything scientific and modern was seen as progress, and progress was good. In the 1960s, the space race Reprinted with permission. All rights reser ved. Page 9 AS SEEN IN USA TODAY’S MONEY SECTION, WEDNESDAY, JUNE 22, 2005 lit up a generation of tech believers. In the 1990s, we all thought the Internet was going to "change everything" and swore it was the most significant human development since the Sumerians invented writing. vaccination leagues, IEEE's Andrews says. Typists at first resisted carbon paper, thinking it would threaten their jobs. The first electronic computers stirred fears that companies were building "electric brains." IBM CEO Thomas Watson Sr. made speeches saying the machines would never be able to think. The crummy economies of the 1930s, 1970s and early 2000s wiped out a lot of that smiley-faced buoyancy. Once in a while, progress would take a devastating blow, such as in 1979, when Three Mile Island threatened to melt through the Earth's crust and make half of Pennsylvania even less habitable than normal. Nuclear power never regained its footing in the USA. Then there's the flip side. In the 1940s, people labeled DDT the wonder pesticide. By the 1960s, Rachel Carlson published Silent Spring, alleging that DDT caused cancer and other environmental problems. The stuff was banned in the USA in 1973. The odd part, though, is that while in the middle of the debate about some technology, it's impossible to know which side is right. History is packed with examples of skepticism that turned out to be unfounded, and sanguinity that was misplaced. The story of X-rays and other radiation is among the most bizarre. In the early 20th century, beauty shops used doses of X-rays to make unwanted facial and body hair fall out. Physicians prescribed radioactive radium for heart trouble, arthritis and other ailments. For a while in Europe, a candy company marketed chocolate bars laced with radium as a "rejuvenator." In the early 1900s, natural gas companies struggled to persuade homeowners to switch from wood or coal stoves to gas stoves. Obviously, none of that was a very good idea. "Gas is invisible and potentially explosive," says Marian Calabro, president of CorporateHistory.net. Wood or coal stoves "were messy and labor-intensive, but at least homeowners knew what they were dealing with." Gas companies mounted a PR campaign behind the slogan, "Now you're cooking with gas." By 1930, people saw that the homes of early adopters didn't get blown up, and the ease of the use of gas won out over any remaining safety concerns, Calabro says. The fears had been unfounded. We really can't tell whether the naked protesters in Chicago are flakes or prophets. Nanotechnology might turn out to be like natural gas -- an efficient, safe technology that benefits millions of people. Or it could be this generation's X-ray, and our grandchildren will guffaw at our naivete for putting it in our pants. The same goes for RFID or any other technology that's making people wary. Either way, it seems like it's better to ask the questions rather than swallow the optimism whole. Similarly, when Edward Jenner invented the smallpox vaccine in the late 1700s, the public protested, even setting up anti- Reprinted with permission. All rights reser ved. Page 10 DISCUSSION QUESTIONS ADDITIONAL RESOURCES 1. Why do globalization and the U.S.’s growing economic needs make innovation crucial? University of Maryland 2 Should students today embrace technology wholeheartedly without fully understanding the sacrifice of some worthwhile qualities of past inventions? Are all the “old ways” destined to the heaps of extinction or relegated to the category of Neanderthal? 3. One aspect of entrepreneurship is dealing with change. What are some drastic changes entrepreneurs have faced during the past 10 years? Which changes have improved life for entrepreneurs? Which have been detrimental for business? 4. What are some of the ethical issues entrepreneurs face? As a budding entrepreneur, to what extent are you willing to give up some of the “purity” of your art to meet customers’ demands? http://www.MTECHVentures.umd.edu/ resources/university.html Consortium for Entrepreneurship Education http://entre-ed.org MIT Entrepreneurship Center www.Entrepreneurship.mit.edu 5. List three ways to test the durability of an idea today that would not have been available in the past. FUTURE IMPLICATIONS What definitions have changed as a result of technological advances and alterations in entrepreneurship? What other definitions do you see evolving or changing in the near future? For example: a. The term “workplace” today means one thing for students and yet something entirely different for people who physically commute or telecommute. b. Has the definition of “customer” changed, or have we merely changed the way we visualize customers? c. Have the definitions of intellectual property, trademarks and copyrights changed, or is the issue today more about valuing someone else’s property? d. Discuss the definition of “ownership” as it relates to the articles in the package. Notes: © Copyright 2006 USA TODAY, a division of Gannett Co. Inc. All rights reser ved. Page 11 M E E T T HE E X P E R T … Karen Thornton is the director of the nation’s f irst living-lear ning entrepreneurship program, which began in 2000 at the University of Maryland, College Park. She manages the day-to-day op erations and provides on-site mentoring and coaching to students who par ticipate in the award-winning residential cur r iculum, the Hinman Campus Entrepreneurship Opportunities (CEOs) Program. Other features of the program include the annual Universit y of Mar yland $50K Business Plan Competition and a wide variety of internships. The Hinman CEO program also works with high school and community college students. The Hinman CEOs program is one of three aspects of MTech Ventures at Maryland. T hor nton manages the business development activities of MTECH Ventures Karen Thornton and overse es a c adre of e duc ational Program participants join as sophomores and juniors programs and activities offered through the Clark from all academic disciplines, with as many as 90 School of Engineering. students living together each year. The students are encouraged to team up in dorm rooms, specially- A native of Hampton, Va., Thornton managed a stellar equipped meeting rooms and a business center to career playing the French horn in orchestras and discuss ideas, dreams and possibilities. The two-year groups around the world for about 25 years, taught program requires students to take a three-credit music at both Florida’s Jacksonville University and entrepreneurial course that includes lectures and a Maryland’s Towson University. She earned Bachelor weekly speaker series. Students also earn three-credit and Master of Music Performance degrees from Florida hours in a ‘sp e cial topics’ c ourse that includes State University, ARCM from the Royal College of analyzing case studies. Music, London, and an MBA from the University of Maryland. Thornton, who also was a Fulbright Scholar, Each fall, the Hinman CEOS are involve d in an came to work at Maryland as the Director of External orientation event that includes various team-building Affairs and Human Resources for the Department of activities. There are also cookouts, socials and the Electrical and Computer Engineering. annual Technology Start-Up Boot Camp for faculty. © Copyright 2006 USA TODAY, a division of Gannett Co. Inc. All rights reser ved. Page 12