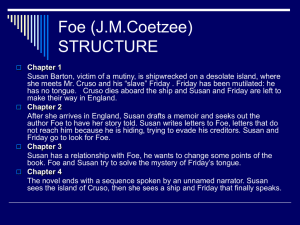

Acts of Writing and Questions of Power: From Daniel Defoe to J.M.

advertisement